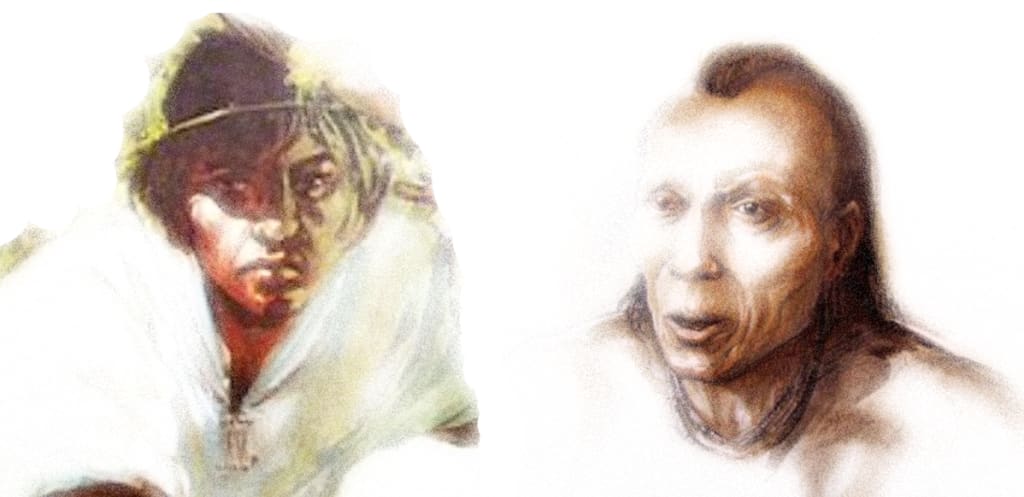

Canek and Kandiaronk

A Tale from North-America

It is said that the American

is the perfect mean

between the European and the Indian.

Moreau de St. Méry

.

Amerindian voices were starting to raise in 2XXX and it came to their ears two names from far away but aligned in vision: from the Huron tribe in the north, the Wendat, Kandiaronk (1625-1701), from the Maya in the south, Canek (1731-1731). Both of them regarded as heroes by their peoples. What would it be like to bring them back together from the dead? Fortunately AI now could make it possible, so by means of rescuing both their consciousness (their thoughts, their words plus all the history of humanity that went after their death), they were able to make them talk with one another, having as the only topic in mind their cultural shock when facing the Westerner people. They did have a Westerner interlocutor, McKone, to query further about their perceptions. In what follows, I reproduce a little fragment of their enlightening and fictitious conversation. To these days, 5025, they remain part of the Earth-Human Heritage (which aims to rescue the very best of our species), so-called our gift to the Universe.

.

Kandiaronk: What would you say Canek is what distinguishes the man from the brute?

Canek: Some say it’s the soul. But this is the opinion of the proud. Others say it’s the reason. But this is the belief of philosophers. I will say that I believe in another difference: the difference that mostly separates the man from the brute is the former’s ability to repress and kill his appetite.

Kandiaronk: I agree. What kind of human, what species of creature, must Europeans be, that they have to be forced to do good, and only refrain from evil because of fear of punishment?

McKone: I have heard that the Wendat does have a legal code, but do you mean laws of coercive or punitive nature?

Kandiaronk: Indeed. I spent six years reflecting on the state of European society and I still can’t think of a single way they act that’s not inhuman, and I genuinely think this can only be the case, as long as you stick to the distinctions of “mine” and “thine”. Later in the twentieth century this famous rock band could see it and depict it beautifully.

McKone: Do you mean…?

All through the day I-me-mine; I-me-mine; I-me-mine…

All I can hear I-me-mine; I-me-mine; I-me-mine…

I-me-me-mine; I-me-me-mine; I-me-me-mine…

From The Beatles.

Kandiaronk: Yes, that song.

Canek: You know it’s interesting that you mentioned this because in my culture, some Mayan languages don’t even have the pronoun “I”. In Tojolabal, for example, we only have tik, which means “we” and all decisions are made bearing in mind what is good for the whole community and not in the pursuit of individual interests.

McKone: That’s exactly what was missed! Even when in English we had it all the time in front of us! We could’ve seen it clearly by turning upside down the word, the letter “m” in ME and becoming WE. Now I just remembered Mohamed Ali’s poem Me We about one man’s transition from one to the many, singularity to plurality, and selfishness to altruism.

Kandiaronk: It seems he could read the way Aztecs read codexes: from all different perspectives.

Canek: For us this we is not only the people but it includes the planet as well. We are tierra, meaning we are the planet, the soil, the ground. Tierra is at the same time “soil”, “land” and “Earth”. Everything depends on the place man occupies on the tierra.

Kandiaronk: The Pachamama, the goddess representing Mother Earth for the Quechua people of South America’s Andes region (descendants of the Inca civilization). Pachamama embodied nature and is believed to protect humanity while providing essential resources for life.

Mc Kone: This Mother Earth reminded me of the word for “land” in Finnish: maa. Funny! Anyway, I have heard that the Quechua were even giving water to the land before starting going up the mountain.

Canek: I would not be surprised if they did: the discord and successes of men are explained if we remember their place near the tierra. Thus we see that we, the Indians, live close to the tierra. We sleep in peace on the breast of the tierra, we know its voices and feel the warmth of its depths. We perceive the scent of the tierra; a scent that enriches the paths. The Whites have forgotten what the tierra is. They pass over it, crushing and trampling the grace of its roses. They are the wind that breaks and leaps over the face of the stones.

Kandiaronk: They refuse to see what the Cree used to claim: “Only when the last tree has been cut down, the last river poisoned, and the last fish caught, will you realize that money cannot be eaten.” I can clearly see how money is the devil of devils, the source of all evils, the bane of souls and slaughterhouse of the living. Money is the father of luxury, lasciviousness, intrigues, trickery, lies, betrayal, insincerity – of all the worst behavior. Fathers sell their children, husbands their wives, wives betray their husbands, brothers kill each other, friends are false, and all because of money. This is why we Wendat refuse to touch or even look at silver. The whole apparatus of trying to force people to behave well would be unnecessary if they did not also maintain a contrary apparatus that encourages people to behave badly, an apparatus consisting of money, property rights and the resultant pursuit of material self-interest.

Canek: And yet self-interest is never enough. It just came to mind something I read long ago. I would say this belong to a time where the corruption of money was still non-existent. Some lords sought to muster armies to defend the lands they governed. First, they summoned the cruelest men because they assumed they were familiar with blood; and so they marshaled their armies among the people of the prisons and slaughterhouses. But it soon happened that when these people saw themselves facing the enemy, they paled and threw away their weapons. They then turned to the strongest: the quarrymen and miners. To these they gave armor and heavy weapons. In this way, they were dispatched to fight. But it so happened that the mere presence of the enemy made their arms weak and their hearts faint. They then turned, with good advice, to those who, without being bloodthirsty or strong, were courageous and had something to defend in justice: such as the land they work on, the women they sleep with, and the children with whose graces they delight. Thus, when the occasion arose, these men fought with such fury that they scattered their opponents and were forever freed from their threats and discord.

McKonne: That is exactly who you are. There are many records of settlers who adopted into indigenous societies: they almost never wanted to go back, because they saw that you only care about what is really real at the end of the day.

Canek: Yes, you’re right. I remember a brother from Spain, who fought bravely for our community. Later on came our dear “Carlitos”, Carlos Lenkersdorf, German linguist and philosopher who put on record everything about the Tojolabal language. We was fascinated that there was no “I” pronoun and envisioned a philosophy based on “we” instead.

Kandiaronk: Over and over I have set forth the qualities that we Wendat believe ought to define humanity –wisdom, reason, equity— and demonstrated that the existence of separate material interests knocks all these on the head. A man motivated purely by self-interest cannot be a man of reason. For us it has always been clear that those who are only qualified to eat, drink, sleep and take pleasure would languish and die.

McKone: I have heard that your ideas were indeed behind the ideas of the French Enlightenment: they inspired a literary genre and influenced thinkers like Montesquieu, Rousseau, Voltaire, and Leibniz — injecting Indigenous critiques of European society into mainstream intellectual discourse.

Canek: I agree with Kandiaronk, but apart from reason, there is also emotion. For example, although unknown, the number of stars and the number of grains of sand exists. But what exists and cannot be counted and is felt here within requires a word to express it. This word, in this case, would be immensity.

McKone: You make me think now of Kant’s faculty of judgment to grasp aesthetics (opposite to pure reason that deals with knowledge and practical reason that deals with ethics), and with this “immensity” word you remind me of his description of the sublime, opposite to beautiful: whatever is beautiful is constrained by limits.

Canek: Yes, that’s exactly what immensity is: limitless, infinite. “Immensity” is like a word moist with mystery. With it, one need not count either the stars or the grains of sand. We have exchanged knowledge for emotion: which is also a way of penetrating the truth of things.

Kandiaronk: This word would be an accurate one to describe the Great Spirit, the orenda, for it exists in all animals, plants, rivers, celestial bodies, and even tools. It has also to do with the interaction between them: always based on reciprocity, respect and communal balance.

Canek: Yes, Kandiaronk, the Whites also have orenda. Therefore I would say the fruit of these lands depends on the union of what is dormant in our hands and what is awake in theirs. We are the earth; they are the wind. In us the seeds ripen; in them the branches air. We nourish the roots; they nourish the leaves. Beneath our feet flow the waters of the ‘cenotes’. We are the land. They are above in the air. They are the wind. I once noticed this child: he had Indian blood and a Spanish face; he spoke Mayan and wrote Spanish. In him lived the voices that were spoken and the words that were written. He was neither of the land nor of the wind. In him, reason and feeling intertwined. He was neither from below nor from above. He was where he belonged. Humanity as a whole is like the echo that fuses with a new name, in the heights of the Spirit, the voices that are spoken and the voices that are silenced.

.

.

.

__________________________________________

Based on Kandiaronk’s and Canek’s words taken from:

* The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, by David Graeber and David Wengrow

* Canek Historia Y Leyenda De Un Héroe Maya, by Ermilo Abreu Gómez

About the Creator

Laura Rodben

Stray polyglot globetrotter and word-weaver. Languages have been "doors of perception" that approach the world and dilute/delete borders. Philosophy, literature, art and meditation: my pillars.

https://laurarodben.substack.com/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.