Blood on the Eve of Freedom: The Forgotten Horror of Babrra, 1948

Blood on the Eve of Freedom

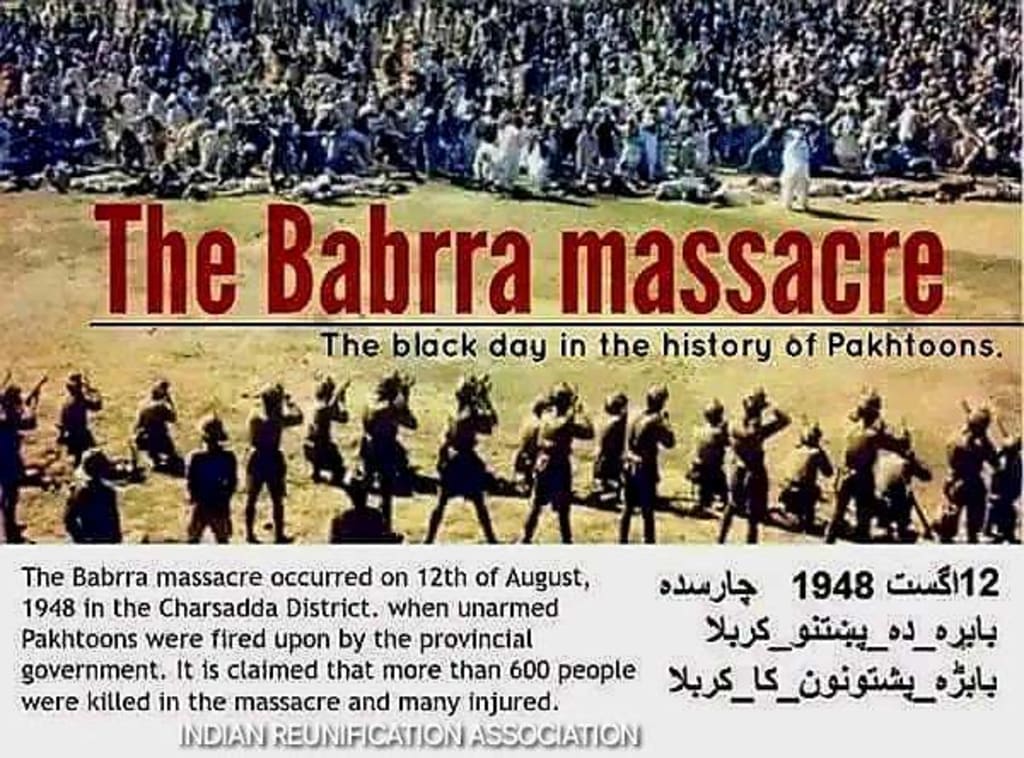

The air over Babrra, Charsadda, on August 12, 1948, hung thick with dust and desperation. Just two days before Pakistan would celebrate its first anniversary of independence, thousands of Pashtun men, women, and children gathered on the open ground. They were not enemies of the state they had helped create; they were its citizens, members of the non-violent Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) movement, founded by the "Frontier Gandhi," Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. Their crime? Peacefully demanding the restoration of their fundamental rights – rights they believed were promised by the new nation of Pakistan.

The Khudai Khidmatgars, known for their distinctive red shirts and commitment to Gandhian principles, had been banned by the fledgling Pakistani state. Their leaders were imprisoned without trial. The gathering at Babrra was a final, desperate plea for justice – a plea to be heard by the government in Peshawar and Karachi. They sought the release of their imprisoned comrades and the freedom to pursue their political and social goals within Pakistan. They came unarmed, trusting in the power of peaceful assembly.

What met them was not dialogue, but the cold steel of state machinery. The provincial government of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), led by the Chief Minister Abdul Qayyum Khan, viewed the Khudai Khidmatgars not as citizens, but as a threat to the central authority. He imposed Section 144, prohibiting the gathering. When the peaceful protesters, convinced of the righteousness of their cause, remained steadfast, the order was given.

The massacre began not with a warning volley, but with deliberate, sustained fire. Police, positioned strategically around the grounds, opened up with rifles. The crack of gunfire ripped through the air, instantly transforming the scene of peaceful protest into a charnel ground. Panic erupted. Men, women, and children – farmers, laborers, elders – scrambled for cover that didn’t exist on the open field. Dust choked the air, mingling with the acrid smell of gunpowder and the metallic tang of blood. White shalwar kameez blossomed crimson. Screams of terror and cries of the wounded replaced the earlier chants for justice.

Eyewitness accounts and fragmented records paint a scene of unparalleled horror. People were shot point-blank as they tried to flee. Bodies fell upon bodies. One survivor recalled seeing a woman shot while clutching her child. The firing continued relentlessly until, chillingly, the police ran low on ammunition. The exact death toll remains obscured by time and suppression – estimates range from 15 to over 150, with hundreds more wounded. Many victims were buried hastily in mass graves nearby, some reportedly bulldozed in the days that followed to erase the evidence.

The true measure of the atrocity, however, lies not just in the numbers, but in the cold-blooded justification offered afterward. In the provincial assembly, when questioned about the slaughter of unarmed citizens, Chief Minister Abdul Qayyum Khan delivered a statement echoing the infamous callousness of General Dyer after Jallianwala Bagh:

“I had imposed Section 144 at Babrra. When the people did not disperse, the shots were fired at them. They were lucky that the police’s ammunition ran out; otherwise not a single soul would have survived.”

This boastful admission revealed a terrifying absence of humanity – a state official openly declaring his intent for total annihilation had the means been available.

The Babrra Massacre was a brutal act of state violence perpetrated by Pakistanis against fellow Pakistanis, Muslims against Muslims, within the first year of independence. It shattered the illusion of unity and exposed the harsh realities of power consolidation. The irony was crushing: just 48 hours before celebrating liberation from colonial rule, the new state had replicated the colonial tactic of mass murder against its own citizens demanding their rights. As Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the prominent Bengali leader and future Prime Minister, declared in Dhaka in 1950, the events at Babrra had indeed "surpassed the 1919 Massacre committed by British in ‘Jallianwala Bagh’."

Yet, while Jallianwala Bagh became a symbol of colonial brutality etched into the subcontinent's memory, Babrra faded into the shadows of Pakistan's official history. The "Pashtun Karbala" remains a wound largely unacknowledged, a testament to the forgotten cost of dissent in the early, fragile years of the nation. The blood that soaked the ground at Babrra on August 12, 1948, remains a stark, haunting reminder of the day freedom's promise was betrayed by its own guardians.

About the Creator

Ainullah sazo

Ainullah, an MSC graduate in Geography and Regional Planning, researches Earth’s systems, land behavior, and environmental risks. Passionate about science, he creates clear, informative content to raise awareness about geological changes.,,

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.