Aba Women's Riot

The Revolt That Shook Colonial Nigeria

In the humid December of 1929, the dusty streets of southeastern Nigeria echoed, not with gunfire, but with the songs, chants, and defiant cries of thousands of women. They were not armed with weapons. They carried palm fronds, danced in circles, and raised their voices in a way the British colonial administration had never seen before.

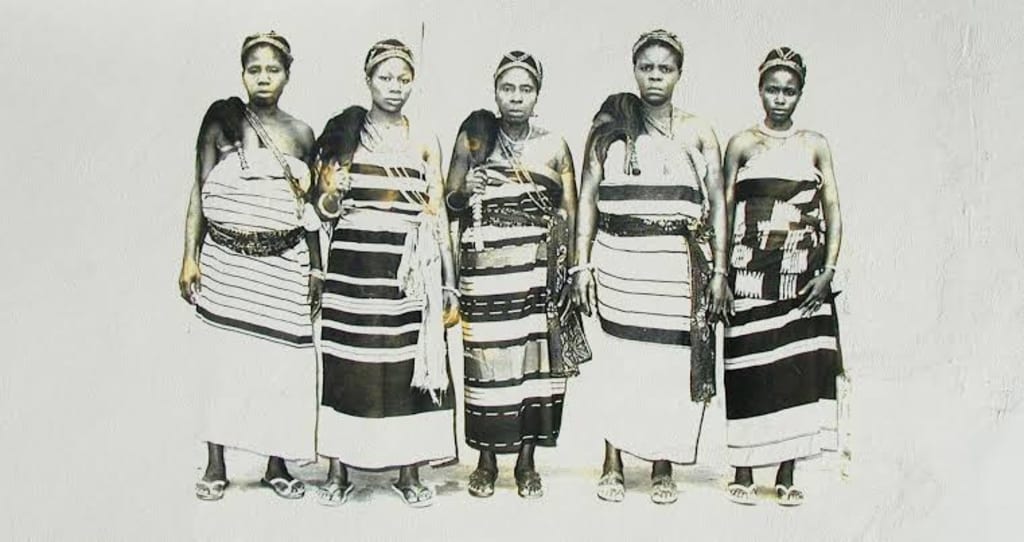

This was not a minor protest. It was one of the most powerful uprisings in West Africa’s colonial history. It was a movement led entirely by women—market women, mothers, widows, and daughters, who decided they had endured enough. History would remember it as the Aba Women’s Riot, or more rightly, the Aba Women’s War of 1929.

By the late 1920s, the British had established their system of indirect rule in Nigeria. They appointed Warrant Chiefs, often ignoring traditional governance structures. These warrant chiefs were mostly men who had been hand-picked, and many were unpopular within their communities.

At the same time, the colonial government introduced new forms of taxation. The men were already being taxed, but there were growing fears that women, who played a major role in the local economy through trade and agriculture, would soon be taxed as well.

For Igbo and Ibibio women, this was more than economics. They had long held important roles in their communities, including running markets and using collective action to keep leadership in check. The colonial administration had sidelined them from decision-making, and this new tax policy became the final straw.

The fire started in the small town of Oloko in the Bende Division. A census official named Mark Emereuwa, working for Warrant Chief Okugo, approached a widow named Nwanyeruwa and instructed her to “count her goats and people” for taxation.

Nwanyeruwa was shocked. In Igbo society, women were not usually taxed. She challenged him, asking, "Was your mother counted?" The confrontation grew heated, and she refused to cooperate.

This incident spread rapidly. Women in neighboring villages heard what had happened and recognized the danger. They mobilized through their age-old communication networks, spreading palm fronds as signals and passing messages through song and market gatherings. The response was swift and massive.

Within days, over 10,000 women from different towns across the Igbo and Ibibio regions gathered in Oloko. These women were not disorganized. They drew on a traditional protest system known as “sitting on a man," a method where women surrounded a man’s house or office, dancing, singing, mocking, and chanting until he was held accountable.

They targeted warrant chiefs, local courts, and colonial offices, demanding justice and the reversal of oppressive policies. Their protests spread across towns like Aba, Umuahia, Owerri, and beyond.

British colonial authorities were stunned. They had underestimated the organizational power of these women, who moved in coordinated waves from village to village.

As the protests grew, the colonial government responded with force. Troops were deployed. In some towns, they opened fire on the protesters. By the end of the uprising, over 50 women were killed and many more were injured.

But the British had learned a lesson. The scale and determination of the women forced the colonial administration to abandon plans to tax women and to restructure the warrant chief system. Several unpopular chiefs were removed, and policies were re-examined.

The Aba Women’s Riot was not just a tax protest. It was one of the first major anti-colonial uprisings in West Africa, and it was led by women. It challenged both colonial authority and patriarchal structures, showing that women’s voices could shake the pillars of power.

These women did not have newspapers or microphones. They did not have social media. But through unity, courage, and cultural intelligence, they shook an empire.

Nearly a century later, the Aba Women’s War remains a powerful reminder of how collective action can bring change. It is a story often overlooked in global history books, but its impact continues to echo in Nigeria’s struggle for independence and women’s rights movements today.

Their legacy is not just in the changes they forced but in the message they left behind: When ordinary people rise together, history is forced to listen.

About the Creator

Stories You Never Heard

Based on True Life Stories

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.