Work, Sex, Death, and Dance: All That Jazz in the Modern Eye

The Beat Goes On for Fosse’s Masterpiece

Bob Fosse, like so many super-talented people, is so loaded with it that his personal life is all messed up, but unlike so many of them, he has attacked the problem by a therapy available to few: he has written about it and broadcast it in this extraordinary film, All That Jazz (1979), regarded as a timeless classic.

Fosse (pronounced fossi) worked in theater and dance most of his life, and was a workaholic, which may have had something to do with his obsessions with sex and death. Trying to get a handle on it for himself, he represented death as an angelically beautiful woman dressed in chiffon white, complete with hat, gloves, and one red rose, who makes cynical comments about his life at each encounter [What! the rose!]

Fosse, who was responsible for Cabaret and Dancin’ and who danced a charming and seductive snake in a highly underrated film The Little Prince, has done everything in this film except play himself — that job is accomplished superbly by a man who looks, acts, dances and talks like him, Roy Scheider.

It doesn’t matter that there is no one in the picture whose name immediately strikes one as “famous,” because everyone in the cast, from ex-wife Leland Palmer, to current mistress Ann Reinking, to his daughter, a lovely young dancer, Janet Folds, Ben Vereen catches the ultimate phone folly of a TV variety show host and Cliff Gorman recalls Lenny Bruce’s monologue on death to a fitting fare-thee-well.

The biggest problem with the picture is that it is too much: too loud, too busy, too full — a critique that still resonates with some modern audiences who find its intensity overwhelming on today’s high-definition screens.

Fosse shoots reels that ended up on the cutting room floor (one hopes kept, for probably there’s enough to do another picture!). The dances are almost frenetic, the emotions thick with tension as one overlays another and you fear the pile will, like anything topheavy, do a Humpty Dumpty fall.

[Spoilers ahead]!!!

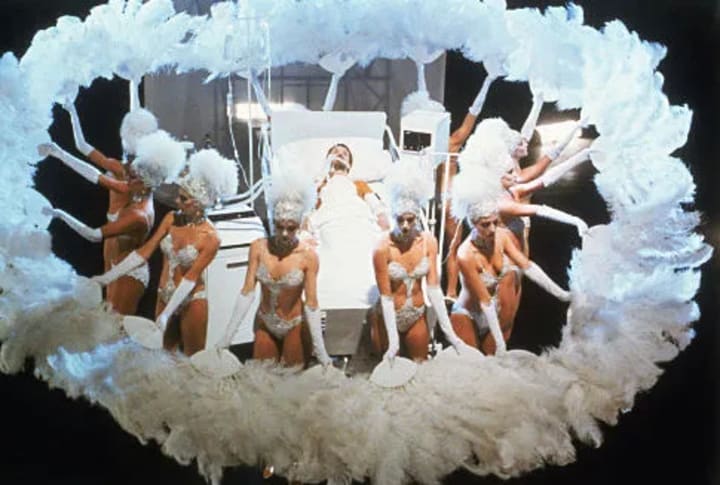

The fact that this is obviously what Fosse wants us to understand makes it no less an unnerving experience, a dance is intersected with shots of an actual open-heart surgery operation — a scene that still shocks even in an era of graphic medical dramas — or as a laughing, drinking group of people jump to a lonely Fosse roaming an empty white hospital corridor reminiscent of Kafka; in despair over his illness, as he bangs his head against the wall until the blood leaves a red line.

Nowhere is religion or a deity mentioned — the work/sex/death problem must be worked out by the man himself, and this is plain. There is an interesting undercurrent involved here: if man does not have the security blanket of being told what to believe, especially about what happens to him after death, then he is not only responsible to himself, but he also has a lot more to sort out, a lot more thinking; knowledge must be balanced with the jumble in one’s head, which can sometimes be so deafening as to preclude organized thought.

Better that, of course, than organized religion, except that along the road to organized thought, one grabs at everything — in Fosse’s case, patently, work and sex.

There is a wryly humorous but utterly delightful scene with the angel of death, Jessica Lange, where Fosse remembers a time when he lived in ménage-a-trois, and one of the girls eventually left, leaving a tender note saying, “I can no longer share you with anyone else.”

Lange’s comment: “What makes you think the note was to you?”

The Lenny Bruce routine was the one he developed around 1969 after the publication of Dr. Kubler-Ross’ book On Death and Dying. As Bruce goes through the five stages of emotional reaction to the prospect of one’s death, Fosse is using this routine in a film he is making, and so his editing of the film is used as a springboard for his own later emotions in the hospital.

Bruce is gruesomely funny as he hits the third state, Bargaining (“Hey, you don’t want me; I’m scarcely weaned yet; take my mother!” — Reminiscent of Orwell’s 1984) but Fosse is even more sophisticated and amusing as he spreads his arms, in his short hospital gown, and hollers at the ceiling, “What’s the matter, you don’t like Musical Comedy?”

He will not allow himself to die yet, there is too much work to be done on the picture. He has gone through the first two stages of Denial and Anger, and is hitting the bad Depression of the fourth stage, but when he finally hits the fifth and last stage of Acceptance, and he goes toward Lange, it is with the same smile he has shown us before when another sexual experience comes his way.

The picture also makes it plain that the first stage of Denial is itself a death-wish, as we ignore our illness and exasperate the doctors in a refusal to believe there is anything wrong by continuing the smoking, drinking and pep-pilled pursuit of work and of the opposite sex (which caused the problem in the first place — a behavior that, in 2025, we might view through the lens of modern mental health discussions on self-destructive tendencies.)

However, none of this is to say that the film is not a magnificent theater piece as well. The dancing is all innovative and superb, the music just right, the ambiance of the theater exciting, the emotions real — elements that continue to captivate audiences streaming the film today.

There is a beautiful little dance between Schneider and his daughter, which is tenderness itself. There are some funny scenes with the backers of the show, the old moneybags men with calculators for hearts, that show the theatre-money situation as it is, and the angry bitterness which must be felt by the creative people who can’t exist without the money — a dynamic that still rings true in today’s era of big-budget Broadway and streaming platform investments.

There is an opening rehearsal scene right out of Chorus Line only more so. There is a deft scene showing Fosse as a boy, working the burlesque houses as a tap dancer. There is a mood-shifting twin scene later as he first berates, then encourages one of the dancers. There is an erotic group dance number unlike anything you’ve ever seen before.

If you know about the wonderful early television Playhouse 90 (we need to be friends!) you will recall that some of the best scripts were written by Robert Alan Arthur, who, allying himself, collaborated with Fosse on the writing of this script. We can only hope he lived long enough to see the good product that was emerging, a film that remains a benchmark for blending dance and drama half a century later.

This story was first published on Medium:

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.