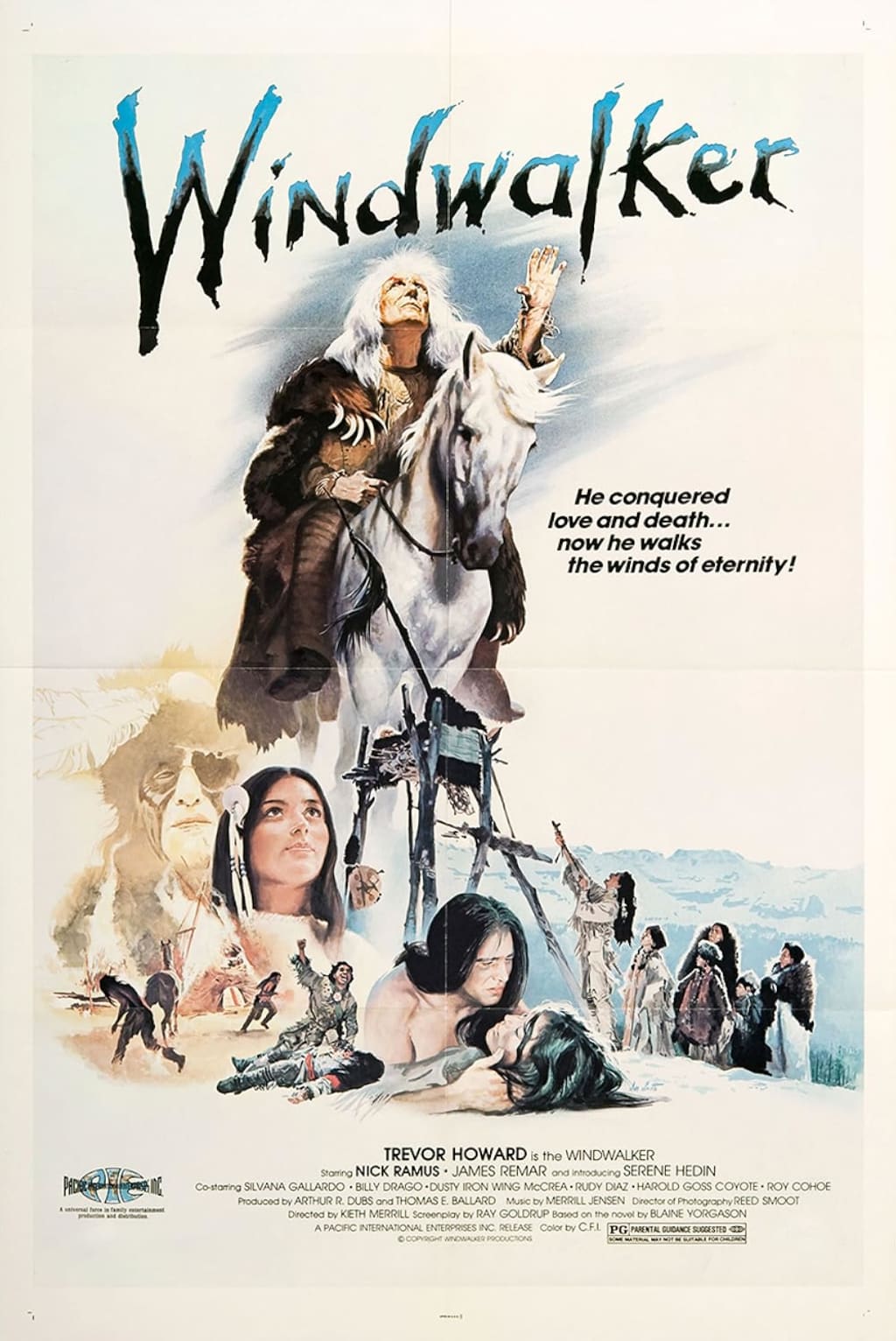

Windwalker (1980): The Forgotten Western Told in Cheyenne and Crow

Windwalker (1980) is one of the few American films spoken almost entirely in Native languages. Here’s how filmmakers handled Cheyenne and Crow dialogue, how Native communities responded, and why its legacy remains complex.

A Western That Broke the Rules

When people think of 1980s Westerns, they usually recall revisionist works like Heaven’s Gate or nostalgic star vehicles. Few remember Kieth Merrill’s Windwalker (released in 1980, though often grouped with early 80s films), a modestly budgeted historical drama with one extraordinary claim: with the exception of an English-language narration, every line of dialogue is spoken in Cheyenne and Crow. Subtitled for mainstream audiences, Windwalker dared to put Native voices front and center — a choice virtually unheard of in Hollywood at the time.

⸻

Filmmakers’ Approach to Language

The production leaned into authenticity as its major selling point. Cheyenne and Crow were chosen not as exotic window dressing, but as the languages spoken by the characters in their time and place. Merrill and his team cast Indigenous actors who could deliver the lines with accuracy and credibility, supplemented with guidance from Native speakers.

Instead of dubbing into English — the standard industry shortcut — they subtitled the dialogue. That decision preserved the cadence and rhythm of the languages while making the film accessible to wider audiences. The one exception was a voice-over narration in English, included as a guide for viewers unfamiliar with the cultural context.

By letting Indigenous languages dominate the soundtrack, Windwalker avoided the “Hollywood Indian” trope of gibberish or pidgin speech. For audiences in 1980, it was startling, immersive, and unprecedented.

⸻

How Native Communities and Critics Responded

Reactions were varied and complex.

On one side, mainstream critics praised the film’s respectfulness. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert recommended it on Sneak Previews, noting how the use of Cheyenne and Crow forced audiences to identify with Native perspectives rather than with the usual white protagonists. The mostly Native cast — aside from British actor Trevor Howard as the elderly Windwalker — was likewise a break from Hollywood tradition.

Many Native viewers and activists saw the choice as overdue recognition. It was rare to see their languages treated with dignity on the big screen, and rarer still to see entire communities represented in a story not filtered through white leads.

Yet not everyone was satisfied. Scholars and Native commentators noted that the film still fell into familiar patterns — “noble” versus “savage” tribes, simplistic moral binaries, and visual framing that sometimes perpetuated old stereotypes. Later film historians have argued that while Windwalker represented progress, it wasn’t free from the biases of its time.

⸻

The Academy Awards Problem

The film’s bold linguistic choice also created an unexpected industry snag. Because almost all of its dialogue was in non-English languages, Windwalker could not be considered for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards. By rule, only a recognized nation-state can submit a film in that category. Since Cheyenne and Crow are Indigenous languages within the United States, the film had no path to eligibility.

For Native communities, the irony was painful: the use of authentic Native speech effectively excluded the film from recognition, while films in French or Italian faced no such barriers. The episode underscored how U.S. institutions treat Indigenous cultures as “foreign” within their own homeland.

⸻

Legacy Beyond the Box Office

Commercially, Windwalker came and went with little fanfare. But in the decades since, it has gained a kind of cult status as a bold experiment in representation. University courses on Native cinema often screen it as a discussion piece, and contemporary Native artists — including Gail Tremblay, who weaves film strips into visual art — have used Windwalker as raw material for critiques of Native representation.

The film remains a unique artifact: neither a box-office hit nor a total misfire, neither a perfect portrayal of Native life nor a dismissible Hollywood stereotype. It occupies a rare middle ground, remembered less for its narrative than for the fact that audiences in 1980 sat in theaters reading subtitles in Cheyenne and Crow.

⸻

Why Windwalker Still Matters

The most important legacy of Windwalker is its insistence that Native languages are not ornamental but essential. At a time when many Indigenous languages faced erasure, seeing them dominate a feature film was a radical act.

Yes, the film is dated, and yes, it remains flawed. But its daring linguistic choice — and the conversations it sparked in Native and non-Native communities alike — gives it a lasting cultural importance. In a decade when most Westerns were either nostalgic retreads or box-office disasters, Windwalker stands apart as a genuine, if imperfect, attempt to let Indigenous voices speak for themselves.

Subscribe to Movies of the 80s here on Vocal and on YouTube. YouTube.com/Moviesofthe80s.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.