The literary journey as a catalyst

Many celebrated literary works feature journeys - but what is their significance?

Throughout the history of literature, from Homer down to the present day, journeys have been used symbolically as catalysts to convey important truths about the human condition.

Journeys in literature

Journeys have featured in literature from the earliest times. Doubtless some of the earliest stories told round the camp fire before writing was invented were tales of journeys beyond the mountains and across the rivers, and of the strange and wonderful things that the traveller encountered. A little bit of embellishment could be expected, if only to keep the audience interested. After all, they were hardly going to be able to contradict the story-teller! When the stories started to be recorded in writing, the journey was still a constant theme.

Homer’s Odyssey (8th century BC)

A prime example is Homer’s Odyssey, telling the story of the return of Odysseus from the Trojan War, a journey that took ten years to cover a distance of only a few hundred miles!

But that is the whole point. The journey is not so much a physical one as a personal one. All the adventures that Odysseus undertakes, including encounters with monsters such as Polyphemus the Cyclops, and Scylla and Charibdis, and his capture by the nymph Calypso, are stages in his personal progress. We are constantly reminded that he is coming home to his wife and son, and we are invited to judge his conduct as he deals with various temptations along the way. The physical journey is therefore a catalyst for his moral and developmental journey. The man who eventually reaches the end of the journey is not the same man who started it.

Joyce’s Ulysses (1918)

One of the greatest works of 20th century literature was James Joyce’s Ulysses (the Latinised form of the Greek Odysseus), a modern re-telling of the ancient Greek epic. Here is another physical journey, in the form of a single day’s wandering through the streets and buildings of Dublin, closely paralleled with the episodes of Odysseus’s wanderings, and another example of a catalyst at work.

In Joyce’s case, the journey acts as a means of portraying the confusing and eccentric lives of a small cast of characters who are far from the heroes of Homer’s works. Leopold Bloom is both hero and anti-hero, a man whom we can both admire and despise, who both belongs to where he is and, as an Irish Jew, does not belong. He is both hero and fool, as revealed by his various encounters along the way. He is therefore just like most of Joyce’s readers.

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (c.1387)

It cannot be said that every journey in literature works in the same way as for Homer and Joyce. One of the most famous literary journeys must be that of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The pilgrims meet at the start of their journey to Canterbury and resolve to tell stories as they make their way along. However, the journey is almost incidental to the tales. We learn nothing about the pilgrimage, and there are only a few incidents along the way that have any bearing on the stories or their tellers. The journey is merely a framework, a peg on which to hang a series of narratives.

This is therefore an example of a “non-catalyst” journey, and it is included here merely to illustrate the difference.

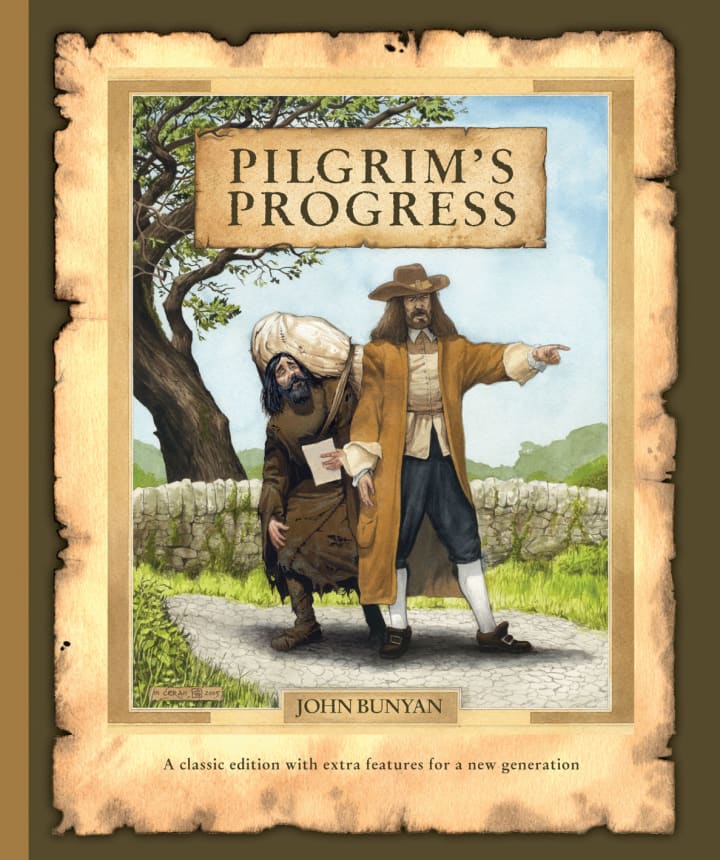

Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678)

The word “catalyst” implies that something changes as a result of the impetus given by an event. That is certainly true in the case of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, in which the progress is a spiritual one, based on the concept of the life of man being a journey from birth to death, during which he must also journey from the City of Destruction through the temptations of Vanity Fair and the hard times of the Slough of Despond to eventual salvation in the Celestial City. Here the journey is an allegory, and the end result is an extended sermon.

Boswell’s Hebrides Journal (1785)

A journey of a very different kind is that of James Boswell and Dr Samuel Johnson, as told in the former’s The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785).

This is a description of a real journey, in which real places and real people are encountered, but what makes this an example of journey as catalyst is that Boswell uses it as a vehicle to paint a portrait of an extraordinary man, namely Dr Johnson. Johnson was 64 at the time, overweight, set in his ways, opinionated, and apt to express himself volubly on anything he either appreciated or hated. He found plenty to comment on during the journey, and Boswell was on hand to record it all.

Children’s Literature

Journeys that change people are typical of all literatures and in all ages. They are often found in children’s literature, partly because the concept of a journey is ideally suited to the pattern of the “what happened next” story of which children have always been fond. The journey story is simpler to tell than one that involves a complicated plot, and it can be easily interrupted when it is time to go to sleep!

Among classic children’s journey stories we can include Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1872), and, crossing the Pond, Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).

Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-5)

However, mention must be made in this context of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Whether Bilbo Baggins is greatly changed by his adventures in the former book is a moot point, but his nephew Frodo returns from his own long journey as a very different character from when he started. The journey format is used to portray a vast range of challenges to the human (or hobbit) psyche, resulting in important lessons being learned about the value of true friendship, how to respond to triumph and disaster, and how to win through against everything that fate can throw at you.

Summary

Many more examples of the journey as catalyst could have been included, in both British and American literature.

The important point to be noted is that such works are not pure travelogues but occasions to add value in one way or another. It must also be stressed that a journey that is not used in such a way is not necessarily inferior to most of the examples noted above – as The Canterbury Tales makes abundantly clear.

About the Creator

John Welford

John was a retired librarian, having spent most of his career in academic and industrial libraries.

He wrote on a number of subjects and also wrote stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Unfortunately John died in early July.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.