Thank You, Makima

or: for real this time ;)

About a year ago, I did something I am not very proud of: I published a crappy opinion piece.

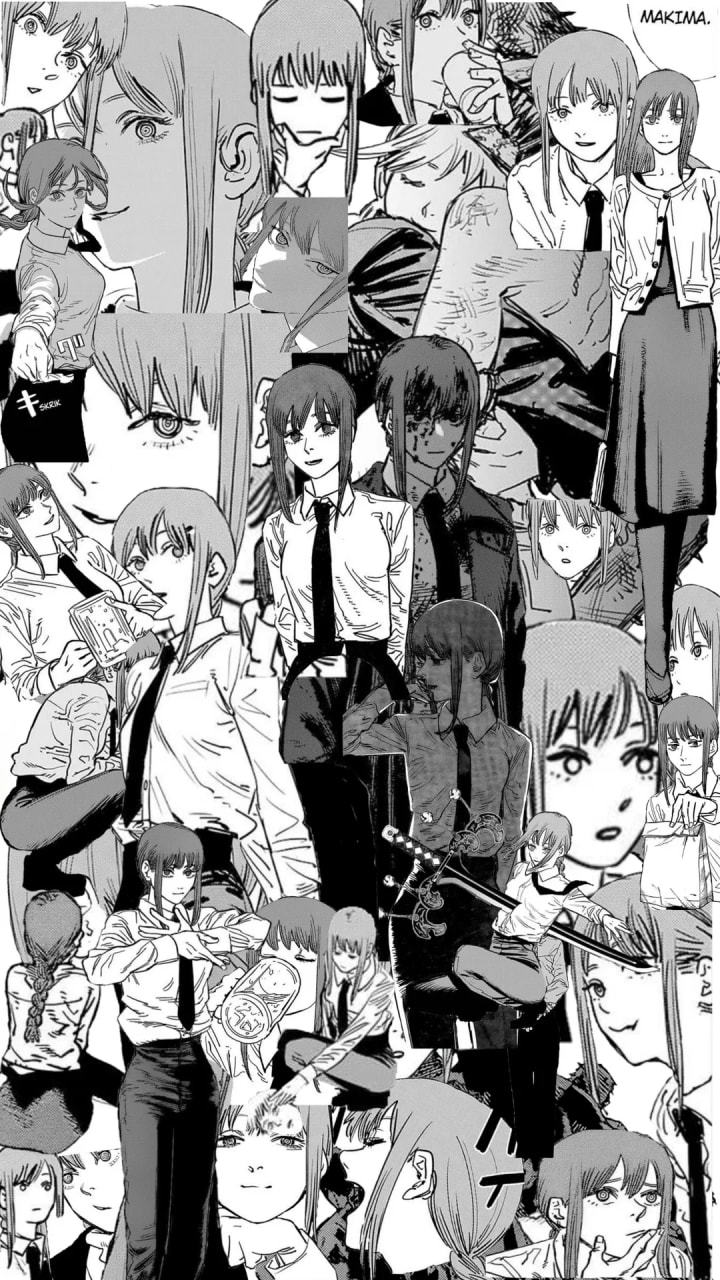

Said crappy opinion piece resides here on Vocal, and it is—unfortunately—about one of my favorite characters in all of anime and manga: Makima.

In this aforementioned crappy opinion piece, I mostly drone on about how Makima stands out among her fellow female characters in anime and manga. If you’re into anime and manga, you probably know about, or have at least heard of, the conundrum some male manga authors tend to face with struggling to write complex, fleshed out women. There are definitely many exceptions to this—Attack on Titan immediately comes to mind for me—but it’s just one of those things that’s unfortunately common. Women in a lot of anime/manga are often just there to serve a man’s story rather than to be their own independent characters with significant goals, wants, and desires of their own.

But Makima is so much more than just a “good female character”, and I regret boxing her in as just simply that in my original piece dedicated to her. So today, I’d like to do her some real justice by sharing, in detail, why she is one of my favorite fictional villains of all time.

Makima is the primary antagonist of the absurdist, brilliant shonen manga Chainsaw Man. I’ve yapped enough in the past about Chainsaw Man, even publishing a piece dedicated solely to its phenomenal art, which I will link at the bottom of this article. I love it very much, and I can’t recommend it highly enough.

(Preface: If you are interested in reading this manga spoiler-free, please click off of this and go do so!)

Makima is, by far, one of the most striking antagonists I have ever experienced in all my years of reading, as well as one of the most unique—which is interesting, because upon a first glance, many probably wouldn’t think she’s very unique at all.

But there are many layers to Makima. There are so many aspects to her that make her so fascinating when looking at her character arc as a whole: her mysterious aura, her manipulative nature, her mannerisms, her goals and dreams, and her ways of going about achieving those goals and dreams are just a few examples.

But before any of that, it is important to contemplate who exactly Makima is when we see her for the first time.

First impressions are often wrong, it is said. But there is such a difficulty in fully grasping a solid first impression of Makima. Mystery and mystique are built into the very core of her being. There is such a vagueness, and almost a manipulation, in the way Makima is first presented to us, the audience, as well as to our protagonist—almost as if it is clear, even from the beginning, that she does not want to be truly known or deciphered.

Denji is brash and naïve. Power is loud and obnoxious. Aki is stoic and responsible. Makima, on the other hand, is calm and composed, and always professional, but that’s all we can really discern, making her a lot less personable than the rest of the cast. While other characters have defining personality traits, Makima has almost none. Readers may assume she is anything from a domineering boss to a well-meaning powerful figure to just your average femme fatale, and none of those initial perceptions would be wrong; they’re just not the full picture.

The story takes its time with Makima’s character, showing her to us piece by piece, clue by clue, moment by moment. This immersion into getting to know her slowly and carefully, the exact way our protagonist Denji gets to know her, is such a clever way of building her up before everything comes crashing down.

A good villain, to me, is always ruthless yet understandable. Even if you wouldn’t choose to follow in their footsteps, you should be able to see their warped perspectives of their world and understand why they would do the things they do. One does not necessarily have to be a sympathetic character to be a good antagonist, but their goals and actions must have a focus and a depth that the audience finds interesting and alluring.

Makima certainly falls into this category of villain, and a big driving factor of this is the build up to her reveal as an antagonist. We only see glimpses and fragments of Makima’s true self throughout the story, and it is always interesting and captivating to watch her in all her strange, serene secrecy and to learn more about her, like a seemingly simple puzzle turning out to be much more complicated as it comes together slowly, piece by piece.

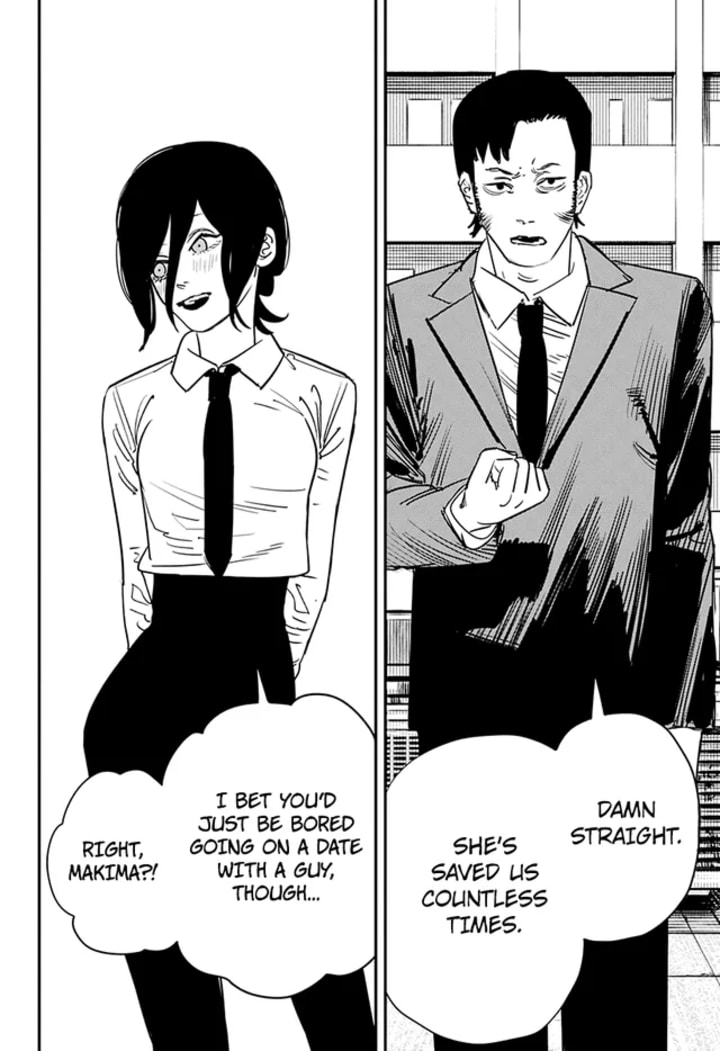

There’s one scene I’d love to start off with discussing before we delve into Makima fully. Fairly early on in the series, Makima is speaking to the yakuza, the Japanese mafia, about matters concerning business with the Gun Devil; this picture above is a rather famously memed-on panel of her doing so.

Whether the underlying sexual meaning here was intended or not (the “casting couch” type trope, with a lone attractive woman sitting in front of several larger men before things “escalate”), I do not know. However, I do personally believe it was done purposefully, because Fujimoto is quite well known for rather provocative and sexual imagery in his work—it’s okay, Fujimoto, you dog, we still love you. But I also like to believe it was purposeful due to the irony alongside the dirty-minded comedy, as it is Makima, the woman and the being who should be submissive and “at the mercy” of these powerful men behind her, who truly holds the power here, unbeknownst to them.

The yakuza boss tells Makima that they are a necessary evil. He makes the yakuza sound like the protectors of Japan, these noble, decent people, and he says if they did not carry out the malicious deeds and work that they do, foreign gangs would do it instead and wreak much more violence and havoc on all of the country.

Makima does not hesitate for even a moment in calling them out on this bluff. Perhaps it is the arrogance, the gall, the shine of yakuza hypocrisy that struck her so deeply into doing so, readers may initially think. Truly, it is much more than that.

This scene is one of the first really significant insights into Makima’s character. It is one of the first times we see her displaying emotion and opening herself up enough to speak down to very important and dangerous people, who she is clearly and thoroughly unimpressed and unintimidated by. She does not hesitate in calling their deeming of themselves a necessary evil a lie, because it is a lie to her; she does not view them as such.

Makima views the yakuza as irritating, insignificant beings in her path, waiting to be easily swept aside, rather than any form of necessary evil. She effectively and easily puts them in their place by threatening their loved ones and by using a small amount of her power to subdue them into fear and submission.

She, in turn, very much views herself as the real necessary evil. But more on that later.

From the very start, whether it’s manipulating a sixteen-year-old boy with promises of sexual favors, brutally murdering dozens of enemies in an unsettling, elusive way, or presenting the yakuza with the gored out eyeballs of their loved ones, Makima is a morally ambiguous character at best, which creates an intrigue into her psyche and her potential goals. She is never painted as someone who is genuinely good, or genuinely kind, or even very fair. She is kind to Denji at times, but she always speaks down to him and clearly does not respect him as anything but a warm, willing, and working body, whereas Denji adores her and is constantly seeking her approval. She is manipulative to him, using his wants and desires to guide him exactly where she needs him. She is always shown as rather stoic and calm, even with deception clear under the surface of her every move.

But as the plot further unravels, we get to see the true being underneath that calm, smiling exterior: a cruel god of sorts with immense power and a plan—a being who wants to keep the very world under her thumb for the sake of her own dreams. She herself, as she subtlety states in the previous scene, is the true “necessary evil” that the yakuza claims to be through her own perception, only she has the power and the ability to back it up.

What exactly drives Makima’s manipulative cruelty that we see her exhibit? The answer is, quite simply, that it is Makima’s true nature that fuels it.

It is revealed to us near the end of Part 1 of the manga that Makima is, in fact, not a human, but the Control Devil; this puts quite a lot into perspective. It is in the nature of Devils to be self-serving and often unrelenting, and all of Makima’s secrecy, brutality, and subtle manipulations of others begin to make sense in context.

This remains a key thing to keep in mind about Makima: she is not human. She does not understand the human experience. The moment we learn she is a Devil, everything comes together a little more. Makima, after the reveal, was so clearly cosplaying as a human being the entire time in a way that makes perfect sense, and her lack of humanity makes her performance both extremely unsettling and deeply fascinating in hindsight. As much as Makima looked human, and sold herself as a human to everyone around her, there was always something that was off, something that others deemed felt strange or wrong about her—an emptiness, or perhaps a simple lack of a moral code commonly associated with human beings.

As a Devil, human morality has nothing to do with Makima. She is incapable of harboring or experiencing love, empathy, betrayal, cruelty, or kindness in the traditional human sense. This is why even in pretending to be a human, she could not sell her role fully in a way that was convincing to everyone that she was worth trusting. Several characters, with Kishibe being the most significant example, know that something was off with Makima, something beyond simple untrustworthiness; they just couldn’t put their finger on what.

But even more interestingly, in contrast with her true Devil persona, Makima’s end goal is very human at its core. Her dream of creating a perfect world with Pochita, of wanting to connect with another being, is an incredibly human desire, fueled by a lack of understanding said human desire. It is an immensely fascinating dream for a character like her to have.

As inhuman antagonists always tend to do, Makima fails to see her dream for how very human it is due to her overall underestimation of humans. It is built into Makima to control everything and everyone around her, to the point that she cannot see the humanity she looks down upon within her own reflection, even when it is so glaringly obvious to us as readers.

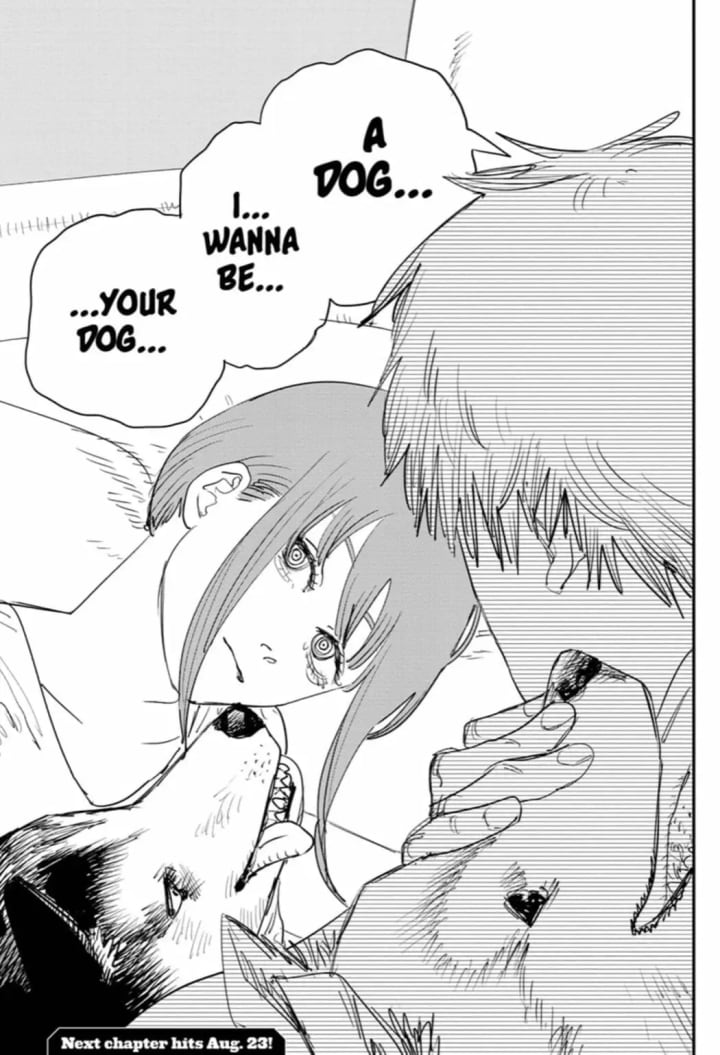

In her final fight against Denji and Pochita, Makima states that she loves humans in the same way that humans love dogs: they are loyal, and easily handled. They are clever, and yet so very stupid. They are amusing to watch. And most importantly, they love her.

This is another incredibly significant section of dialogue when it comes to understanding Makima’s character. As the Control Devil, Makima knows she is feared, and she does not despise being feared. I personally believe that, as the clear emotional sadist she proves herself to be, she revels in the fear people and Devils have of her as simply a part of her disposition; she always seems to relish in revealing her true self to others, and in hurting them as well.

But Makima also wants to be loved—in, and this is very important, the only way she understands what that can even mean as a Devil. She looks for it in the pockets of her life the only way she knows how, and in the only place she can look: within the spheres of her own creation. In a world that she controls so entirely, she likes to feel loved by those around her, even if that love is forced, because that is the only way love can exist for her in the day to day, within the same mundanity humans are experiencing alongside her.

One can argue that true love is never something that is forced, and I think that’s a fair and very complex discussion to have. But different types of love, whether called by that name or not, often seem to exist within the concepts of control, abuse, and inequality in a way that is often shamed when spoken about as love.

Healthy love is a beautiful thing, something we can’t quite explain very well as much as we can feel it. But unhealthy love, forced love, or love within a rigid structure or a power dynamic is sometimes the only love a person is able to have or give or experience, and this is the case for Makima. The “love”, or rather the worship, that she draws out from others through her power is simply adoration and submission, and her fondness for that “love” she receives from them even through control, I believe, is genuine. When she reanimates and controls the Devils she’s killed previously in the fight against Denji/Pochita, she subconsciously has them all fall in love with her, showing readers her skewed yet existing desire for love and affection from those around her.

But even more significant is the type of love that Makima desired from Pochita (her idealized version of him, at least) more than anything: equality, connection, and a sense of understanding.

Though Makima could not fully understand it, she craved true connection more than anything else, and there is something deeply heart-wrenching about a being so incapable of experiencing something wanting to experience it more than anything, without even realizing it. She couldn’t help but desire control due to her natural state of being, but control was not what she truly desires at her core. What she truly desires is to be accepted, embraced, and loved by another—the ideal human experience.

This is where the sadness of Makima’s character and her desire for connection comes from. True love, as humanity sees it, is not something her mind can truly understand, akin to how a human mind is incapable of understanding how the Christian God always is, always was, and always shall be (there’s an extensive amount of Christian symbolism and imagery in Chainsaw Man, but that’s an article for another day). But still, despite not understanding how it can be possible, Christians still believe God always was and always will be. And still, despite not understanding how humans experience love and connection, Makima craves it all the same.

On the other hand, the genuineness of the love Makima can experience and understand through forcing it out of others is somewhat vapid and unappealing, and even almost childlike. Making a bunch of people fall in love with you wherever you go sounds like something a manipulative third grader would do to feel loved and wanted. But this actually makes sense, because Makima, like Denji, is emotionally stunted when it comes to understanding human love. To Makima, worship is love. Submission is affection. Forced obedience is, and always was, the only thing connecting her to others, and this doesn’t just go for humans. Only in defeating Pochita could Makima ever see a true potential connection with him; only through control can she achieve any sort of relationship with another. But the type of connection she dreams of subconsciously is simply beyond her reach due to her inability to escape who she is, and that is a truly lonely existence to live.

The parallel between Denji and Makima and the way they individually view and talk about the concept of love is something I rarely ever see mentioned—which is understandable, since if you love Denji, comparing his character to Makima, the being who destroyed everything he ever loved in his own life, seems a little wild and morally reprehensible—but hear me out.

Denji, throughout the entire story of Chainsaw Man, is seeking human connection. He is desperate for it. He hungers for it more than anything, at almost every waking moment. We see this in several seemingly silly, stupid ways—Denji wanting to touch a boob, or spend time with a girl, or get to eat toast with butter and jam in the morning. He doesn’t have the ability or the intellect to word it in any other way, but it is clear he is starving for love and affection after such a neglectful, stress-driven life. He wants the comfort of a normal, happy world, and he wants to share this world with other people. He wants to experience connection with other human beings and all else that life has to offer, things he never would have experienced in a million years—had it not been for Makima.

Makima, while deeply flawed in a humanly moralistic sense, has a very similar goal to Denji, almost jarringly so. She also wants to live in her idea of a good and perfect world, free of pain and hardship, free of war and disease, free of all things she deems horrible—but she does not seek to rule over this ideal world of hers alone. She seeks to possess this world through connection with another living being, an equal—a friend. Like Denji, she wants to operate in a world that is good and ideal to her while having a special connection that fulfills her emotionally. And also like Denji, she is too emotionally stunted to understand that is what she truly wants.

It is a very unique and convoluted tie, the bond that connects Denji to Makima in how similar they are in this regard. Both Denji and Makima pursue their own goals concerning their differing views on love and connection—and both of them are continually blindsided and disappointed by how difficult these dreams end up being to obtain.

This is another theme Chainsaw Man repeatedly touches on—the inability to feel as if what you have will ever be enough. Whenever Denji proceeds to meet a goal, he is left underwhelmed or unsatisfied. Jam on toast is delicious to him at first, but pretty soon in the future, it becomes his norm. Getting to hang out with a pretty girl is exciting to him at first, but it’s not enough just to hang around her without touching her. But touching her isn’t enough, either—he wants to have sex with her, that’s the real deal. But having sex with a pretty girl isn’t enough, either. He needs to have a genuine connection with the girl in order to have sex with her; only then will it feel as good and be as special as he wants it to be.

The finish line of wants and needs is continually pushed further and further back as Denji becomes more and more comfortable in his own life, as his dreams become more and more obtainable. And interestingly, the relentlessness and dissatisfaction of the chase for dreams is not only limited to humans in the story. Makima’s dreams of either connecting with Pochita and taking over the world with him or being consumed by him both do not come to fruition. Quanxi’s dream to keep her girlfriends alive and happy is destroyed by Makima. The Doll Devil’s desire to kill Makima for power is ultimately not successful. Even Devils, some of the most powerful beings in the world, face continuous failure as their goals fall through.

One of the primary themes of Chainsaw Man almost certainly has to do with dreams, but what exactly is it? To keep dreaming? To not let dreams get in the way of our present? To focus on the connections we have instead of all the things we could potentially have that may never come to fruition? To accept that even if they did come to fruition, we would still be left craving more? To accept that the idea of a dream will always be better than the reality at hand, yet never as fulfilling? To get up after a dream has failed and keep moving forward?

There is no one single or right answer, and that is what makes Chainsaw Man, its characters, and some of its seemingly mundane plotlines so utterly immersive to contemplate. And Makima, as the face of Chainsaw Man in my mind, represents all of this: the complexity of this back-and-forth battle with humanity and what it stands for, with dreams and what they mean, and with the concept of love and what it means for all living beings. Makima’s perspective on these things is essential to understanding what makes humankind so very different from Devils—and how they are also one in the same.

The final thing I’d love to touch on in this piece is the public perception of Makima: what it is, why it is so, and whether it’s fair or not.

Makima is a very despised character by a lot of Chainsaw Man fans, for a couple of reasons. The first one—and somewhat interestingly, the most prominent one—is her treatment of Denji as far as sexual boundaries go.

Online, especially within the past few years, there’s been a lot of discourse about grooming. Grooming is defined as when an older person seeks out a relationship with a younger person through manipulation tactics, often pursuing them romantically or sexually in the process.

A lot of characters throughout Chainsaw Man take advantage of Denji’s easygoing personality in a way that can certainly be viewed as grooming. Himeno, a character well into her mid-to-late twenties, falls under this category in a way that is even more blatant than Makima. After a night of drinking, she takes a drunk Denji home with the intention of sleeping with him, whilst knowing it is wrong and even outright saying so. This is societally wrong and immoral, and in many countries, blatantly illegal.

Makima, in a human sense, is absolutely grooming Denji from the very start of the story in multiple ways. She knows, as an attractive woman, that he desires her sexually, so she uses that to her advantage, luring him throughout her plan with the promise of granting Denji any wish he wants, even if that wish is sex.

But Makima is not supposed to be a moral character. She is consistently displayed as an abusive figure in Denji’s life—not just romantically or sexually, but maternally as well. She plays all these roles in his life, leading him on and making him believe and trust in her, only to turn them all against him to crush him and keep him down, keep him broken. Her final step in shattering him emotionally was making him confront the harsh realities within his own mind and own up to killing his own father, a memory which he had utterly repressed.

Her goal to utterly break Denji using his own cares, wants, and desires against him was to separate him from Pochita, who she desired a connection with, without Denji, a rather irrelevant human, being in the picture. She was never actually intent on having sex with him. It was yet another false persona she put on to lure him exactly where she wanted him—a means to an end.

As the Control Devil, Makima is extremely manipulative. So obviously, the rules and the laws surrounding sexual consent and the age of consent, as we currently understand them, while often extremely significant to us as people within our respective societies, would as a matter of fact not be significant to a being like Makima. This is clear from her sexual flirtations and manipulations of Denji, which are never justified by the story, let alone treated as actual, genuine romantic moments between two people.

There is a critique to be made, surely, that some of this behavior as exhibited by older women towards a child is displayed as a bit eyebrow-wagging and a bit too “ooh-la-la” for some people’s tastes, but grooming isn’t always evident and seen for how toxic it is, especially through the gaze of a lonely sixteen-year-old boy. And also—guys, I’ll say it again: Fujimoto is a pervert. He just is.

I don’t think Chainsaw Man tries to excuse or glorify grooming as much as it tries to make us understand how messy and disturbing people can be. The common saying of “hurt people hurt people” cannot be applied to Makima, as she is not a person. It can be applied to Himeno, however, who takes a drunk, underage boy home with the intention of having sex with him, despite knowing it is against the law and seen as immoral.

Having lost partner after partner, and being too afraid of ruining the relationship she has with the person she genuinely loves, Himeno knows she could die at any moment. A life such as this, living under the stress of death at any moment, leads to immorality and desperation, hence her trying to sleep with Denji to satiate her own loneliness.

This is not an excuse, not in the slightest—Himeno even voices the following day how glad she is that she didn’t go through with it, as she wouldn’t want to go to jail, which is a wild moment of dialogue—but it is the essential background information that leads to that very uncomfortably sensual and realistically perturbing moment between a drunk Himeno and Denji. Himeno, while painted as a complex character, is never once painted as a good or moral person, nor should she be. She is also not demonized or treated as a monster; she is multi-faceted and very morally grey, and I think that’s okay.

In conclusion: I don’t think the fans who hate Makima for being “a pedo” are wrong, necessarily. I understand where they’re coming from. People have the right to be more sensitive to subject matter like this due to their own personal experiences and outlooks on society, and I get that. But I do think it’s a shame to reduce a character such as Makima’s to simply flirting with a minor, especially since she holds no actual genuine interest in pursuing a sexual relationship with Denji at all.

Also—Himeno’s the real pedo, guys. Come on.

Another reason people hate Makima is because unlike a lot of antagonists, she’s very successful in her pursuit of evil as far as emotional impact goes.

Since Makima infamously kills two very major characters in the manga, many readers find her absolutely despicable and irredeemable. I think a common conception about Makima, due to this emotional reaction people have to despise her for murdering their favorite beloved characters in cold blood—which, within itself, is a fine and understandable reaction to have, if you truly love the characters in the story that much—is that she is only evil, as in purely evil, in a way that paints her as much more surface level than I personally believe she is.

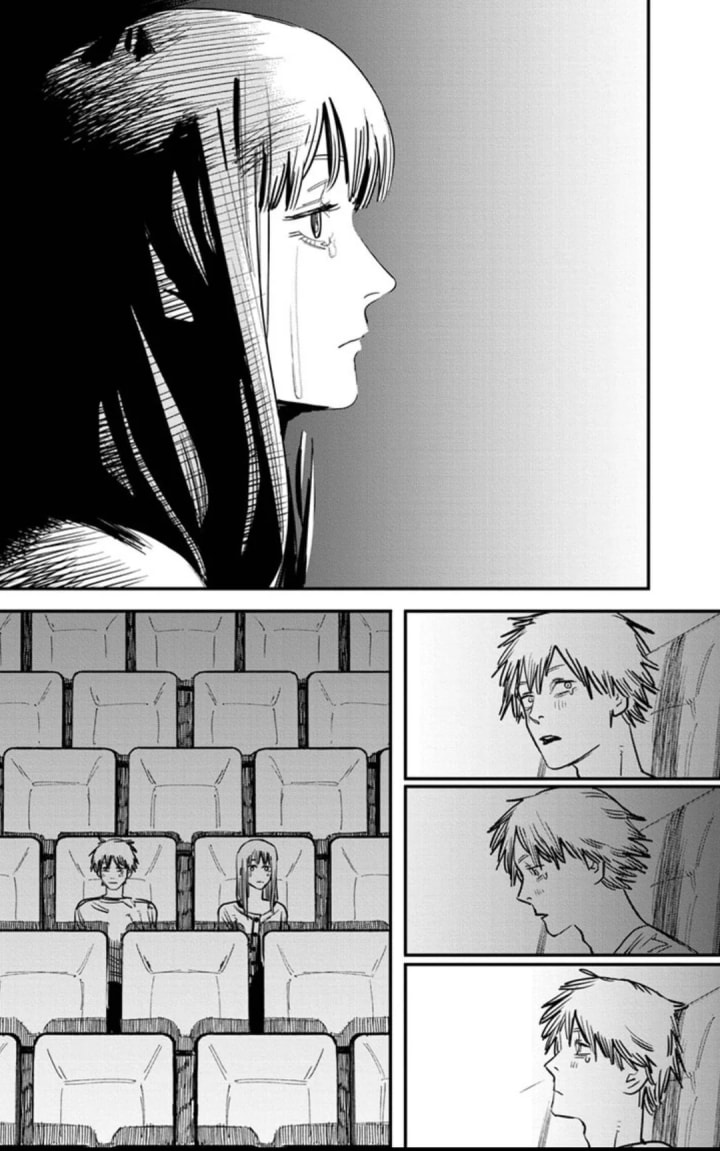

Let’s jump back to a certain famous movie date scene for just a moment:

Denji and Makima go to the movie theater together. At the theater, Denji and Makima hop from film to film, and each one after the next, from their (once again) interestingly matched identical perspectives, is either bad or mediocre. But a subtle moment in the final movie they watch brings Denji to tears, and when he looks over to see Makima at his side, he sees that she is crying too.

There is an incessant debate amongst fans about this scene, about how true and honest Makima’s tears really are in this moment. And that makes sense. After all, we are dealing with the Control Devil over here; it’s very fair to scrutinize her emotional reaction and to question its validity.

I am of the personal opinion that Makima’s tear here serves two purposes. It is indeed to connect with Denji, to manipulate him into believing they have shared an emotional experience together, further ensuring his trust in her for her own gain.

But it also shows that Makima is capable of crying. Her face in the scene is stoic, as it always tends to be. But by the end of her arc, we see and know that Makima is very capable of exhibiting genuine “human” emotions. When she throws back her head and laughs at Denji’s shock and horror over Power’s death, that is a genuine emotional moment from her—and a jarring, phenomenal moment, may I add—and no one really debates that.

This is because the perception of Makima is that she is a purely evil character. Therefore, evil reactions come easily to her. Her joy and pride over seeing Denji so low, so broken, is very real. Her deep-seated repulsion of Denji, this human that has, in her mind, corrupted her only chance at connection with the one supreme being she is deeply inspired by, fuels this emotional response, as well as her own sadistic qualities. So it’s easy to see and believe that Makima means it when she laughs at Denji’s horror and misery.

But what is also shown to be genuine about Makima is her dream. Her dream of an ideal world. Her dream of finally getting to relinquish control, only after achieving total control, in this Orwellian dream landscape of her imagination. Her dream and her desire for this reality is also very genuine, just as genuine as her joy towards Denji’s downfall, driven by an explicit and almost passionate dissatisfaction with the world around her, with the experience she is stuck with having just by being herself. Even with the control she harbors over everything, she still seeks more. Something different—something she cannot quite grasp.

So yes, I believe that the tear Makima sheds over the very human moment of connection between two old friends in the movie served as both a malicious tactic—as is within her nature—and as a true emotional reaction that touched her very soul, intriguing her by showing her something she has never truly understood or experienced, but that she so desperately wants to.

Seeing Makima as only her plan to achieve her perfect world, without the why or the how coming into account, is also just a shame. So in short: I do think it’s kind of ridiculous to hate Makima for killing off good characters. Sorry, guys.

Additionally, when Pochita/Denji asks Makima if there would be bad movies in her perfect world, and she says that no, there would be no need for them, it says everything about the differences between the two, the differences that completely unravel and almost shut down any similarities between the two characters at all.

This whole movie scene is precisely the reason Denji ends up being incapable of hating Makima, despite all the pain she causes him. Despite her curating this life for him and tearing it all down for her own ambition, she still gave him that joy. She gave him a family. She gave him friends. And with the connections he made with those people, with that pain, with those experiences, and with Makima’s life for him, his life became his own, even through her control.

Makima was never able to control the happiness and content he experienced for the first time with other people. Her taking that away from him was painful, but her giving it to him in the first place, despite the reasoning behind it, was a gift. It is because of Makima that Denji was saved, that he was able to connect with others, that he was able to find himself. He was able to experience a life of love and fun and happiness, alongside all the agony and pain, both physical and emotional, that the story of Chainsaw Man fixates so much on, hence all the talk about the addicting escapism of dreams.

Makima granted him his own dream, and even though it was temporary, even though he was never fully satisfied within it when he had it, it was still his. Makima destroying his life did not change one essential fact: that his life was, at that point and forevermore, his own. His memories were his own. His connections were his own. Death and destruction cannot take that away from him. For the first time in his life, Denji was able to own something, to be a part of something so much bigger than himself, so much larger and more significant than his own survival: a life consisting of love.

Even a god of control cannot take our experiences and our love away from us. They cannot strip us of what we have personally experienced, of what we know to be real and true through our own human perspectives.

It is because of this that Makima loses in the end. She is incapable of understanding humanity enough to triumph over Denji, who she did not view as a threat or a challenge in the slightest. But it is of the greatest irony that it is Denji she loses to, not Pochita. Not an equal to her, or a superior to her, but to one of her own dogs—a human.

She isn’t able to see the truth through Denji’s eyes: that it was the gift of this life she granted him, not its loss, that was most significant in the end. It is the existence of bad movies that allows us to relish in the great ones. It is experiencing terror, hardship, and pain that makes experiencing joy, passion, and comfort so very special. And it is experiencing life, in all of its complexities, in all of its joy and pain, that makes humans so tragically, beautifully, and indubitably resilient, even in the face of god herself.

Makima didn’t destroy Denji permanently. She deeply traumatized him, absolutely, and he did crack. He reverted to a broken, mellow state, a shell of himself, after the horrors she inflicted on him. But Makima misunderstood his brokenness as something it was not. She misunderstood that his weakness, his capacity for human love, was actually a strength—the very one that kills her in the end, as Denji slaughters her with a weapon made from his best friend Power’s blood.

Instead of wishing he had never met Power, or Aki, or even Pochita, to avoid the terrible pain of losing them, Denji learns something absolutely essential. He learns it the way all humans learn the very hardest lessons our lives have to offer, slowly and painfully: that having those experiences with those people was worth the pain, and that the love he has, even when at many points he fails to see what he had for others in his life as love, is what made the loss of them so grave, so traumatizing, so terribly unbearable.

In breaking him, Makima’s plan proved Denji’s own humanity to Denji himself, who had started to doubt his capacities for love and connection after he became part Devil. It proved he was capable of love and dealing with pain, and it motivated him not to survive, like he had been operating before he met Makima, but to live. To triumph. To carry on with the memories of all of it in his heart—memories he owns. Memories that can never be controlled.

So Denji, while extremely disturbed and wary of the thought of Makima even well after her death due to the breadth of his trauma, cannot ever truly hate her. It is because of her that he learned to live, and learned what is worth living for: not just dreams, not just distant, glorious goals that strike a beautiful fantasy within our minds, but the magic of the present, and the significance of the connections we make along the way.

That about wraps this up—for now. Makima’s unique, chilling, and utterly complex role as the antagonist of this story is what makes Chainsaw Man such a fantastic analytical dumping ground—I love her so very much. Murder and all. And I love this story.

Thank you guys for reading!

~

My original piece:

More like this:

About the Creator

angela hepworth

Hello! I’m Angela and I enjoy writing fiction, poetry, reviews, and more. I delve into the dark, the sad, the silly, the sexy, and the stupid. Come check me out!

Comments (3)

Angela, I haven't read this yet, but how many spoilers are there for someone who has only watched the fist season of the anime? 😅 I'm conflicted. A 20+ minute read of Angela's writing? YES PLEASE!! 😁 I want to read it now! But a part of me also wants to be surprised when they drop more of the anime and when a lot of the cool scenes come around 🤔

I remember Makima from your previous piece! And I don't think it's crappy at all! How could you even say that? 😭😭😭😭😭😭😭 I already liked Makima from the piece about her and about the Chainsaw Man. So this piece was a real treat for me. I loveeeeee how deep you went and I thank you for this. Also, yes, Himeno does seem more of a pedo than Makima. There's a small typo for the word convincing* in this sentence: *This is why even in pretending to be a human, she could not sell her role fully in a way that was comvincing to everyone that she was worth trusting."

I know nothing at all about Manga and had no context at all for your discussion but I found it compelling nonetheless. This Makima sounds... interesting seems too trite a description. I like the way her eyes are drawn, like they're hypnotic. I loved your analysis.