Frightening and Familiar

Terror in 19th Century Short Stories

The 19th century marked a great period for Gothic literature, reflecting deep cultural anxieties provoked by rapid social and scientific change. As Britain underwent industrialisation, with its sprawling cities and alienating machines, writers increasingly turned to the supernatural and psychological to explore the hidden recesses of the human mind. Gothic fiction flourished as a vehicle for expressing fear of the unknown whether spiritual, moral, or technological, and often drew upon liminal settings and the uncanny to disturb the boundaries between reality and imagination. The short story, emerging as a dominant form during this period, proved especially effective in delivering concentrated doses of terror, often set within claustrophobic or morally ambiguous spaces.

Central to any discussion of Gothic affect is the distinction between terror and horror, famously articulated by Ann Radcliffe in her 1826 essay On the Supernatural in Poetry. Radcliffe defines terror as that which:

“expands the soul and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life,” whereas horror “contracts, freezes, and nearly annihilates them.”

(Radcliffe, 1826, In: Milbank, 1998, p. 156)

Terror, then, is rooted in suspense, dread, and suggestion, while horror is tied to the grotesque and the explicit. The stories explored in my article: Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s The Shadow in the Corner, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, and Charles Dickens’ The Signal-Man each employ techniques of terror rather than overt horror, using ambiguity, psychological disturbance, and symbolic imagery to sustain unease.

My article also examines how these texts construct terror through three core elements: theme, language, and imagery. Thematically, they engage with isolation, the supernatural, guilt, and madness which are forces that unsettle the rational self and suggest a deeper moral or existential fracture. In terms of language, they use manipulations of syntax, diction, and narrative perspective to foster uncertainty and destabilise reader expectations.

Finally, imagery plays a central role in evoking terror, particularly through motifs of darkness, decay, entrapment, and the uncanny. As critics such as Botting (1996) have noted, the Gothic often “articulates ambivalence,” evoking fear not through monsters alone but through the familiar turned strange. In what follows, each story will be analysed for the ways it channels this tradition of terror, showing the complex strategies Gothic writers used to unsettle their readers.

The Shadow in the Corner by Mary Elizabeth Braddon

In Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s The Shadow in the Corner, psychological terror is intricately entwined with supernatural suggestion, creating an atmosphere of unease within the ostensibly safe confines of domestic life. The story explores the collapse of social order and the terrifying eruption of repressed trauma. Braddon employs domestic settings particularly the attic, a classic Gothic liminal space, as the site where secrets fester and threaten to destroy the illusion of harmony. The terror in the narrative emerges not just from spectral presences but from the unraveling of the governess's psyche and the revelation of a concealed past.

The theme of unease within domesticity is central to the story’s Gothic terror. The governess’s narrative voice is initially marked by reason and composure, which contrasts starkly with the descent into madness that follows. As she first describes the attic, the governess states: “I did not see the shadow at first, but I felt it.” This sentence immediately sets the tone for the psychological terror that follows, as the governess’s perception is at odds with rationality: she feels something before she sees it. The shift from rationality to irrationality is key in creating tension, with the governess’s growing unease paralleling the emergence of supernatural forces. Her insistence on maintaining control over the narrative: “I am not a nervous woman”, becomes increasingly strained as the supernatural intrudes upon her rational world, forcing her into a confrontation with her own mental disintegration.

Braddon plays on moral repression in the governess's character. Her rational explanations for the events that unfold act as a veneer, hiding the buried trauma that eventually surfaces. The governess repeatedly insists that there is a logical explanation for the events in the attic, but as the story progresses, her resistance to confronting the past becomes more apparent. In one moment, she reflects on her own psychological state, noting, “It was not my fault; I could not help it. It came upon me like a disease.”

The framing of terror as something invasive, something that gradually consumes her reason, reflects the governess's psychological breakdown. She denies responsibility for the terror, suggesting that she cannot control or understand it, underscoring the Gothic theme of a mind unraveling in the face of overwhelming repression.

In terms of language, Braddon’s use of formal, Victorian prose style is laden with tension. The governess’s calm, restrained narrative voice in the beginning contrasts sharply with the more erratic and panicked tone as the supernatural events unfold. For example, when describing the eerie presence in the attic, the governess writes, “I seemed to see a figure moving in the shadow, a form that had no substance.” The seeming contradiction between the “form” and the absence of substance perfectly encapsulates the unsettling nature of the supernatural in the story: a presence that cannot be fully grasped or understood, yet still elicits terror. The shift from clear, composed language to more fragmented, desperate prose mirrors the governess’s increasing loss of control over her own perceptions and the growing encroachment of terror upon her rational mind.

Imagery plays a crucial role in enhancing the psychological terror. The attic, a space often associated with secrecy and decay, becomes a powerful symbol of the governess's repressed memories. When she is first confronted with the shadow, Braddon describes it as “a dark stain on the carpet,” a visual metaphor for the decay of the governess’s mind and soul. The image of the “stain” suggests something hidden or polluted, much like the trauma she’s tried to suppress.

The shadow itself is a prominent symbol, representing not just a supernatural force but the repressed memories and emotions that have been pushed into the corners of the governess's psyche, only to return in terrifying ways. The presence of shadows in the attic is described as “not a shadow of any person, but of some nameless terror,” further heightening the ambiguity. The uncanny nature of the terror lies in its refusal to be fully understood: it’s neither purely supernatural nor purely psychological but exists as a blend of the two, amplifying the sense of dread.

In the final moments of the story, the governess is overwhelmed by her fear, thinking: “I could not leave the room, for fear the shadow would follow me.” Here, the shadow becomes a metaphor for the governess’s unresolved guilt and trauma. The idea that the terror follows her suggests that repression, whether of memory or emotion, does not erase the past. Rather, it manifests in different, often more terrifying forms. This metaphysical terror, where the boundaries between the psychological and the supernatural blur, is a key feature of Gothic fiction. The governess’s final words: “It is too late to escape now” suggests the inevitability of her descent, underscoring the inescapable nature of the terror that arises from moral repression and the unresolved past.

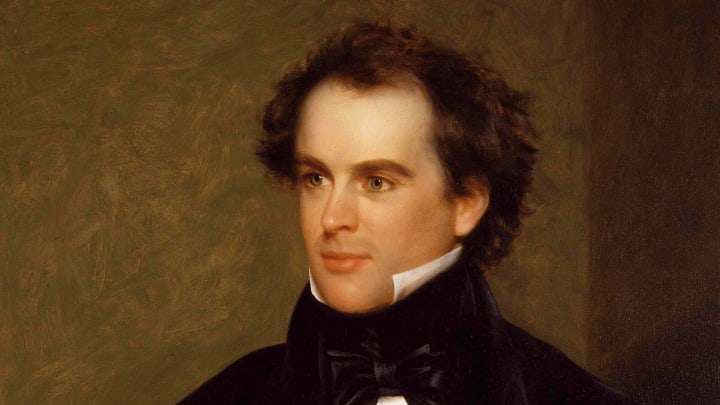

Young Goodman Brown by Nathaniel Hawthorne

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown, moral and religious terror unfolds as the protagonist is forced to confront the darkness within both himself and the society around him. Set in a Puritanical world where moral rectitude and religious faith are paramount, the story examines the fragility of belief and the perilous descent into doubt. Through his journey into the forest, Goodman Brown is confronted not only by external evil but by the duplicitous nature of human virtue and his own vulnerability to temptation. Hawthorne uses the setting, language, and imagery to create an atmosphere of religious crisis, where terror arises from uncertainty and spiritual disillusionment.

The theme of loss of faith is central to the story, as Goodman Brown’s journey forces him to confront the idea that his pious, tightly controlled world is built on a foundation of hypocrisy and duplicity. As he ventures deeper into the forest, he encounters respected members of his community engaging in a satanic ritual, which causes him to question the authenticity of religious virtue.

The figure of his wife, Faith, symbolises Goodman Brown’s belief in the goodness of the world, yet her appearance in the forest, her pink ribbons replaced by the “blackness of night” suggests the fragility of faith in a world filled with moral corruption. As Brown calls out to her, “Faith! Faith! Look up to heaven, and resist the wicked one,” he is desperately clinging to the belief that goodness and innocence can be restored, but the forest and its rituals represent a moral wilderness that seems impossible to escape.

In terms of language, Hawthorne uses archaic, biblical diction to evoke a sense of spiritual weight and to reinforce the religious overtones of the story. The dialogue between characters is often stilted, as if echoing a sense of ritual or scripture, creating a solemn tone. When Goodman Brown first enters the forest, he reflects, “There is no good on earth; and sin is but a name. Come, devil; for to thee is this world given.” The archaic phrasing and direct confrontation with the devil underscore the moral and spiritual struggle Brown faces. The use of allegorical names such as :"Faith" for Goodman Brown’s wife, further emphasises the moral dimension of the narrative. Her name itself acts as a symbol of the protagonist’s own faith, which is continually tested and ultimately shattered by his experiences in the forest.

Hawthorne’s imagery of the forest as a chaotic, unknowable space is central to the story’s sense of religious terror. The forest is described as “dark and gloomy,” with “the path…winding through a dreary wilderness.” The forest is not just a physical space but a metaphorical one, representing a moral wilderness, a place where the boundaries between good and evil become blurred and unclear. The fire, darkness, and storm motifs deepen the sense of turmoil and spiritual conflict. At one point, as Goodman Brown watches the ritual unfold, “the dark rock...seemed to be in the very heart of the wilderness,” symbolising the heart of moral corruption in the world.

The terror in Young Goodman Brown lies in its ambiguity; whether what Brown witnesses is a satanic ritual or a hallucination borne of his own guilt and paranoia. The story leaves the question unanswered, and the fear arises from this uncertainty. Did he truly witness the corruption of his community, or did he simply imagine it in his mind, influenced by his deep Calvinist guilt and fear of damnation? In the final scene, when he returns to the village, he is consumed by the belief that everyone around him is tainted by evil: “With gloomy sadness, and of the world’s illusive mirth,” he observes the townspeople, now irreparably distanced from him. This moral and religious terror ultimately reflects the disillusionment of a man who has lost faith in both humanity and his own capacity for salvation.

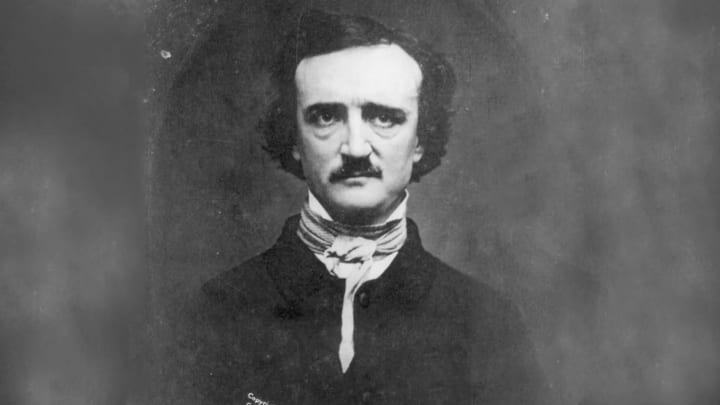

The Cask of Amontillado by Edgar Allan Poe

In Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado, the theme of revenge is explored through the chilling narrative of Montresor, who meticulously plots and executes the brutal murder of his perceived enemy: Fortunato. The story’s terror arises not from chaotic violence but from the cold, calculated precision of Montresor’s actions and the psychological tension he creates by keeping his victim unaware of his fate until the very end. This sense of dread is compounded by themes of pride, madness, and cruelty, as Montresor’s actions are driven by his ego and a desire for personal retribution. The story’s terror emerges from the calm and controlled nature of Montresor’s narrative and the moral corruption that underpins it.

The theme of pride plays a significant role in shaping the terror of the narrative. Montresor’s pride in his family’s honor and his belief in the necessity of exacting revenge for the slights he perceives creates a sense of tension. His elaborate plan to punish Fortunato seems, on the surface, to be a rational response to an offense, but as the story progresses, it becomes evident that Montresor's obsessive pride has led him to a point of madness. His calm demeanor contrasts with the horror of his actions: "I must not only punish but punish with impunity." This rationalisation underscores his inability to feel remorse and marks the moral disintegration that accompanies his vengeful desires. His pride feeds his cruelty, and the terror builds from the reader’s awareness of his deep-seated madness, disguised as an artful, rational plan.

Poe’s use of language is crucial in creating the terrifying atmosphere. Montresor’s narration is marked by meticulous control of tone, with his calm, almost clinical approach to the story’s horrific events heightening the psychological tension. The opening lines:

“The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could; but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge,”

immediately establish Montresor’s cold resolve. His deliberate, measured tone contrasts sharply with the horrific events, creating a sense of detached cruelty. The use of dramatic irony in which the reader knows Montresor’s intentions while Fortunato remains oblivious creates a layer of tension. Montresor’s repeated toast to “your long life” heightens this irony and contributes to the psychological tension: “I drink to your long life,” he says to Fortunato, knowing that the toast is a grim mockery of the fate awaiting him.

The imagery in The Cask of Amontillado reinforces the sense of claustrophobia and slow-building dread. The descent into the catacombs, with their dampness and decaying bones, serves as a powerful metaphor for Fortunato’s impending fate. Poe’s descriptions of the catacombs, with their "nitre" and “gloom,” emphasise the oppressive atmosphere of death and decay, mirroring the suffocating nature of Montresor’s revenge. The jingling of Fortunato’s bells as he is led deeper into the catacombs is a striking auditory detail that contrasts the festive tone of his costume with the ominous silence that envelops them. As the bells ring, they seem to mock his ignorance, amplifying the terror felt by the reader, who is aware of the fatal consequences awaiting Fortunato.

Therefore, Poe creates terror by positioning the reader as a complicit voyeur. By revealing Montresor’s thoughts and actions in advance, the reader becomes an unwilling participant in the crime. The psychological tension stems from the reader’s shared knowledge of the horror and the slow, inevitable approach of Fortunato’s death. The terrifying realization that Montresor’s mind is completely detached from moral consequences places the reader in an uncomfortable position of observing, unable to intervene. The final moments of Fortunato’s entombment: “For the love of God, Montresor!” serve as a chilling reminder of the complete and irreversible destruction of his life, as Montresor’s icy response of “Yes, for the love of God!” reveals the twisted satisfaction he derives from his revenge.

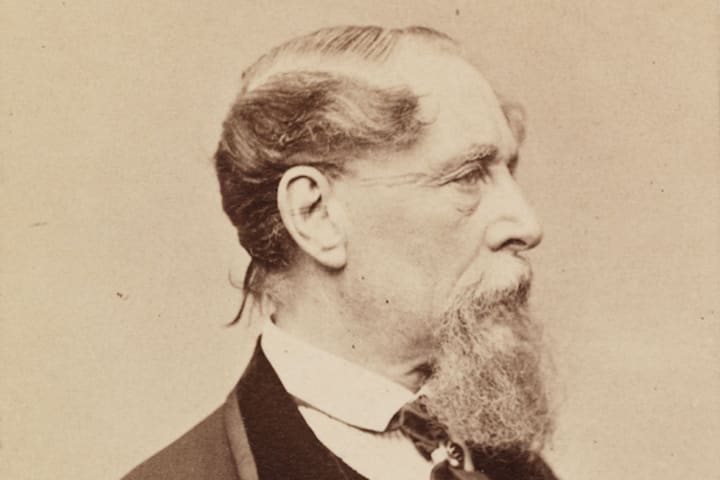

The Signal-Man by Charles Dickens

In The Signal-Man by Charles Dickens, industrial and existential terror are explored through the eerie atmosphere of a railway cutting, where the protagonist, a signalman, experiences terrifying premonitions and a sense of impending doom. The story presents a fatalistic vision of life, in which the characters appear helpless in the face of inevitable disaster, as well as a pervasive sense of miscommunication that heightens the fear of the unknown. Dickens masterfully intertwines the supernatural with the psychological, using both themes and imagery to create an atmosphere of dread and existential anxiety, where technology (the railway itself) becomes a source of horror.

The theme of fatalism is central to the story, with the signalman trapped in a cycle of foreboding and helplessness. He is constantly haunted by the belief that a tragedy is about to occur, as he expresses to the narrator: “I have been walking and walking about the place, and I have not got out of it.” This reflects his feeling of being caught in a web of destiny, unable to escape the doom he senses. The signalman is aware of premonitions and signs that suggest an unavoidable catastrophe, but his warnings are ignored, and his attempts at communication with the outside world seem futile. The repetition of the phrase “Halloa! Below there!” throughout the story emphasises the inevitability of the tragedy that seems to hang over the signalman’s life like a curse, despite his attempts to warn others. The signalman’s desperation to warn the world is mirrored in the narrator’s failure to understand the weight of these warnings, creating a sense of miscommunication that is central to the terror of the story.

In terms of language, Dickens uses a narrative frame to distance the reader from the signalman, thereby amplifying the sense of alienation. The narrator remains an outsider, unable to fully comprehend the signal-man’s experiences. However, when the signalman himself speaks, there is a noticeable shift in tone. His voice conveys a deep despair and uncanny awareness, as he recounts the visions and sensations that have plagued him. His description of the ghostly figure he encounters, “the figure that was on the track,” is delivered with a sense of detachment, underscoring the signalman’s psychological torment and the dread that consumes him.

The imagery in The Signal-Man serves to heighten the story’s sense of terror, particularly in the depiction of the railway cutting, which is presented as a modern hell. The railway cutting, with its "gloomy" atmosphere, “deep trench” and "infernal" feel, becomes a symbol of entrapment; a place where the boundaries between life and death blur. The fog that often envelops the area contributes to the sense of disorientation and danger, as visibility is reduced, and the signalman feels isolated in this technological world. Dickens portrays the railway as a form of modern technology turned monstrous, a force of destruction rather than progress. This technological setting enhances the terror of the story, as it is through the rail system that the signalman’s fate is sealed.

The blending of the supernatural with the psychological in The Signal-Man creates a deep sense of existential terror. While the signal-man appears to experience actual supernatural phenomena, his psychological state marked by: isolation, despair, and a sense of being trapped in an unavoidable fate, also contributes to the story’s haunting atmosphere. The terror is rooted not only in the supernatural appearances but in the psychological collapse of a man who believes he is doomed and unable to communicate his plight to others. The existential condition of the signal-man which is the dread of an inevitable and incomprehensible fate, renders the terror universal, suggesting that we are all vulnerable to forces beyond our control.

Conclusion

Therefore, the terror in these stories is rooted in the collapse of certainty, whether it’s the moral disintegration of characters, the rationality upended by madness, or the spiritual crisis of losing faith. The fear of the unknown and the uncontrollable reverberates throughout.

These techniques remain relevant in modern horror fiction and film, where the collapse of certainty continues to drive narratives. Contemporary horror often mirrors these 19th-century fears, drawing on psychological terror and the uncanny to unsettle audiences and leave them questioning the limits of reality and morality.

Works Cited:

- Batten, P. (2004) Victorian Gothic Fiction. London: Routledge.

- Botting, F. (1996) Gothic. London: Routledge.

- Braddon, M.E. (1860) The Shadow in the Corner. Available at: https://www.steve-calvert.co.uk/the-shadow-in-the-corner-m-e-braddon/

- Clover, C. (1992) Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Dickens, C. (1866) The Signal-Man. Available at: https://shortstoryamerica.com/pdf_classics/dickens_the_signal_man.pdf

- Hawthorne, N. (2004) The Short Stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Ed. Thomas Moser. New York: Norton & Company.

- Hawthorne, N. (1835) Young Goodman Brown. Available at: https://www.columbia.edu/itc/english/f1124y-001/resources/Young_Goodman_Brown.pdf

- Jordan, J. (2007) Dickens and the Industrial Revolution: Technology, Alienation and Humanity in Victorian Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Milbank, A. (1998) Daughters of the House: Modes of the Gothic in Victorian Fiction. London: Macmillan.

- Poe, E. A. (1846) The Cask of Amontillado. Available at: https://poestories.com/read/amontillado

- Poe, E. A. (2009) The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Writings. Ed. David Galloway. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Radcliffe, A. (1826) On the Supernatural in Poetry. In: Milbank, A. (1998) Daughters of the House: Modes of the Gothic in Victorian Fiction. London: Macmillan.

- Schorer, M. (1953) Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Study. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Stewart, S. (2016) The Supernatural in Victorian Literature. London: Routledge.

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (1)

Well written I enjoyed reading this so much ♦️♦️♦️♦️