Book Review: "Reliable Essays" by Clive James (Part 3)

4/5 - an interesting analysis of the Holocaust through two books...

This is part 3 on a series of articles on Clive James' nonfiction essay anthology 'Reliable Essays' and it will be the last part on the series. If you have made it this far on the journey then I would like to thank you massively, I've not done something like this before and it's nice to have the support of my readers even if you just open and read the article without a like or a comment. In previous articles, we have covered topics like Clive James' attitude towards Evelyn Waugh and his works, the way in which he was perhaps very unfair to Marilyn Monroe and Norman Mailer and a bunch of other interesting things. In this section, we will be looking at Primo Levi and Adolf Hitler.

Again, thanks for coming along for the ride if you made it this far.

- Annie

Book Review: "Reliable Essays" by Clive James

(Part 3)

Primo Levi's Last Will and Testament

"He doesn't profess to fully comprehend what went on in the minds of people who could relish doing things to their fellow human beings."

It is clear that Clive James definitely has a soft spot for Primo Levi, affording a fairly middle-of-the-road translation of his works all the passion and love he couldn't give to the entirety of Marilyn Monroe's life even though the essay wasn't even about her particularly, it was meant to be on Mailer's book about her. I promise, I will drop that sooner or later, just not now.

First of all, Clive James likes to prove to the reader he knows what he is talking about when it comes to Primo Levi, however he wrongly assumes Levi's death was a suicide which is generally contested in the close circles that he had. The mythology that Clive James therefore creates from this implication is this was because of the burden of the mental torture Levi had towards once being a a prisoner of the Holocaust, survivor's guilt and furthermore solidifies James' claim that great literature often comes out of suffering - which is simply not true at all.

In fact, great literature may come from suffering, but not exclusively so. That can be well read in the middle class of Europe for example who were the great intellects of the centuries before compulsory education and thus the only literate group of people. They were almost exclusively writing the novels and poetry whilst suffering very few to none of the consequences of daily struggles or things more extreme.

In cases where suffering has created great literature though, it seems that very little of the creation of the literature itself is ascribed to having a great level of intellect. I'd like to hear him say something like this about the Bronte sisters who lived impoverished lives whilst also dying very young. We cannot doubt that storytelling was a big part of their lives from a very young age and thus, even Jane Eyre (which is semi-autobiographical to say the least) may not have been the result of suffering exclusively. But instead a combination of many things.

"All his books deal more or less directly with the disastrous historical earthquake of which the great crimes of Nazi Germany constitute the epicentre, and on whose shifting ground we who are alive still stand."

We have to admit that is a very long-winded way to say "Primo Levi's books tend to be about the crimes of Nazi Germany that linger as shadows long after the regime collapsed" or something like that. If Clive James is going to complain (as we have seen previously) about the translation Nabokov did of Eugene Onegin which he regarded as 'pretentious' then he really has to check himself here.

But if that were not enough, we are about to get a strange barrage of stuff happening regarding Clive James' opinions on the Holocaust which are particularly weirdly worded - somewhat different to how he words his analysis of Levi himself. He often regards the Holocaust with simplistic language he doesn't reserve for other things, even if he does agree as we all do, it was the horror of all horrors. What I would call a 'tonal shift' however slightly so, is a bit jarring to read to say the least.

This on the other hand, is a passage that is actually very well written and explains quite a bit about the tribal mindset of the Nazis if you read it again, just once more:

"The SS taunted the doomed with the assurance that after it was all over, nobody left alive would be able to credit what had happened to the dead, so there would be nothing to mark their passing - not even a memory."

The way in which this is written for example, is much more simply than he affords the actual work and translation of Levi's work, which appears later in the article. It is weird to say the least, but I feel like for such a contentious topic in which everyone universally agrees in the Western World that this was a horrific war crime - Clive James wants to make his stance as clear as physically possible. He runs the risk of oversimplifying, but not here.

"In Auschwitz, most of Levi's fellow Italian Jews died quickly. If they spoke no German and were without special skills, nothing could save them from the gas chambers and the ovens."

He also points out the way in which Primo Levi survived the Holocaust. I'm not sure whether equating it to the way in which Solzhenitsyn survived the Gulags is totally a fair comparison. I can understand it at a base level of what he explains of it, but I think there are things that run much deeper than that. That can come from some readings of Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon. I may be wrong, but I think that the things Clive James says about the Holocaust itself have to be as baseline as possible so that he is not misread in inference.

However, he is again making his point clear that he knew the specific reason that Primo Levi survived the concentration camp. I'm not sure how he would specifically know this but relating it to Solzhenitsyn seems to make sense to the non-interred reader. I think though, I may have a problem that I can't really articulate very well without being too abstract about it. It might come down to a 'correlation doesn't necessarily equal causation' argument but who knows?

"In the special camp for useful workers - it is fully described in his first and richest book "Survival in Auschwitz" - Levi was never far from death, but he survived to write his testimony, in the same way that Solzhenitsyn survived the Gulag, and for the same reason: privilege."

He goes on to explain how Solzhenitsyn was a mathematician and that's what really got him out of harm's way and if Primo Levi hadn't had been a chemist, he would have suffered a horrific fate. But he also goes on to explain how Levi would have known this too - that he was in a pre-21st century way 'checking his privilege' with a side dish of survivor's guilt. But then how does Clive James profess Levi to be one of the great mouths of the survivors of the Holocaust when Levi himself has admitted to "not [being a] true witness" I wonder? Well, I think I'm getting ahead of myself with this idea, but there's plenty there to dissect.

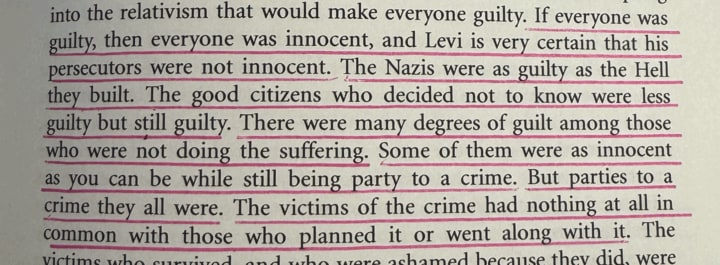

There's an issue I do have with this essay as it doesn't reflect the usual tone that Clive James takes in other essays earlier on in the book. It almost seems like he doesn't know what he wants to say and so creates this hyperbolic step-by-step flowchart of information in order to convey a point that he's not able to articulate fully because he hasn't fleshed it out enough. I mean, just have a look at the thought train he goes on in this passage I've underlined, there is something deeply weird about his tonality - as if he is trying to get his thoughts together as he is writing. That's perhaps why I myself am having a coherency issue when it comes to getting inference from his ideas. You can't tell me there isn't a more succinct way to say this.

It's when he gets back to the way in which Levi understands his own situation and his role as the survivor that we see his thoughts come together in a weird way - because the back and forth between James' own ideas about Levi and the Holocaust are still going on. Needless to say, his ideas are disorganised.

"Levi reminds us that we should not set too much store by the idea that the Nazi extermination programme was within its demented limits, carried out rationally. Much of its cruelty had no rational explanation whatsoever."

He then goes on to explain the historical nature of the trains and honestly, I did not know that and I won't be repeating it because it's awful. But at least we can see where James is coming from in a simpler way. The usual translation gripes start to enter the piece bit by bit, Clive James seeing a real problem with the translation of specific words is a common theme of the book not only this essay. Knowing that 'Levi echoes Dante' gives him an edge when it comes to the translation of the allusions to Dante, which he admits were largely ignored.

This meant that one passage may have been translated (in his words) as 'disliked by everyone' where Levi was actually referring to Dante in that he meant that someone had been rejected by God and all of God's enemies. If you too are familiar with Inferno (as James has rightly given as reference), you will probably be familiar with the idea if not the very line itself.

I think I've spoken enough about this, but here's the deal of the fence I sit on: there are ideas I find quite compelling in here, but the writing is nearly impossible to break through and there's definitely some underdone or perhaps even bad ideas lurking around as well.

Hitler's Unwilling Exculpator

"When it was over after twelve short years of the promised thousand, the memory lingered, a long nightmare about what was once real. It lingers still, causing night sweats."

Note: to 'exculpate' is to clear someone of any wrongdoing. The term 'exculpator' to my knowledge does not exist but is used in the title for effect.

I am going to try and make this one a bit shorter than the last as they are both concerning the same underlying topic: the Holocaust. Clive James starts by taking his stance on the topic, one which we have seen vehemently defended in the last article on Primo Levi. He also asks a question of the idea of Germany and whether 'pinning the Holocaust on what amounts to a German 'national character' makes sense?' He comes to the same conclusion that we do: no it doesn't. There is yet another strange inclusion of a reference to Hieronymus Bosch which I tried hard to make sense of. The last time we saw a reference to this artist we were staring down the end of the George Orwell article The All of Orwell. It made a little bit more sense there, but it seems a bit of an understatement here.

"In a constellation of more than ten thousand camps, the typical camp was not an impersonally efficient death factory: it was a torture garden, with its administrative personnel delightedly indulging themselves in a holiday-packaged by Hieronymus Bosch."

As much as I do understand it however, I don't care for it. I truly don't think this is a topic you need to make obtuse references about in order to prove the point that it was basically Hell on earth if there ever was one. But he goes on immediately to point out that Hannah Arendt was wrong (the famed writing Eichmann in Jerusalem covers the trial of the man who brought in the trains to the death camps) and to look with her eyes is misdirected. I think James is wrong about this and that in order to understand the magnitude of this terror, we must look with all eyes available to us before making any statements for ourselves.

However, he is right about the fact that it was not actually the 'Germans' who were doing it, but the 'Nazis' and we cannot misguide ourselves in not distinguishing between the two. But he makes a weird curve-ball of a remark: 'Didn't we call the soldiers who fought in Vietnam 'the Americans?' Well, no we didn't. We called them the American Army. So I don't understand how this fits in with anything. He does say that we didn't blame the Americans for the atrocities committed there, but nobody was calling them 'the Americans' at the time nor do they really refer to them as that afterwards.

After reiterating the fact that the Nazis often rewarded violence and vengefulness against the Jewish population, he goes on to state that the writer of the book he is reviewing makes his statements with a 'verbal camoulflage' and that is the quotation of the year, isn't it? A man who makes obtuse references to a weird painter, asks rhetorical questions encased in circular logic and fallacy says that someone else has a verbal camoulflage problem. I think we can all see what is wrong here.

This is where you can see it is wrong. First of all, Clive James goes directly on to analyse and critique the use of individual wording and phrasing in the book, stating that words such as 'brutalise' have been used wrong the majority of the time. He also does the same with the word 'decimate' - I'm not sure whether this is important but inference is probably a skill Clive James wants to pick up when reading a book dealing with the Holocaust. Many people are just looking to get words on the paper which can make the reader picture the most horrific scene imaginable. 'Brutalise' and 'decimate' are part of that linguistic stratosphere.

I think one of the things I found the most shocking was this statement here, because when I looked it up, James was actually correct:

"The mobile battalions who conducted so many of the mass shootings in the East were drawn from run-of-the-pavement [Order Police] and many of them were not even Nazi Party members, just ordinary Joes who had been drafted into the police because they didn't meet the physical requirements for the army, let alone the SS elite formations."

That's really self-explanatory and basically tells us about the reach of the Nazi Party and how they practically forced people into some sort of service on the ladder. Of course, abandoning your forced post would be tantamount to helping the Jewish people and thus also tantamount (as Clive James rightly analyses later on) to making an attempt on Hitler's life mainly because Hitler did see it as an attack on his life. Mostly because he was an idiot in my humble opinion.

There is a contentious issue in this essay I want to deal with. It is where James states that '...many of the Nazis were opportunists..." and I find that to be correct. But to go down the sentences and make light of how Joseph Goebells, the maniac he was, did not start off as an anti-Semite is something I cannot agree with. Yes, he may have respected his Jewish scholars in the beginning but we cannot ignore the wave of anti-Semitism which ripped its way through Europe since the time before Shakespeare. It was almost ingrained in the same way there seems to be a rising concern for the Muslim people today. Unfounded and often a vibrant display of idiocy, not really expressed publicly, but still there. Therefore to say Goebells was not an anti-Semite until an opportunity arose is quite a strange statement to make when it can't really be proven.

There is a long analysis of the death marches and those were perhaps some of the saddest things I have ever seen in documentaries after the piles of dead bodies and personal items. People simply marching after being starved half to death and when they fell because they were malnourished and dying, they were savagely beaten. It is, as Clive James rightly analysed, for the Nazis simply a war against the Jewish population.

He goes back to Hannah Arendt:

"Hannah Arendt was not wrong when she said about Nazi Germany in its early stages that only a madman could guess what would happen next."

This is half-correct. You couldn't guess the Holocaust would happen, but you could work out there was a certain amount of animosity towards the Jewish people there inside the party. Nazis, Clive James rightly states, could not be taken at their word and never really told the German people the truths about what was happening, even though many of the perhaps worked it out after a while. He is also right to state that the silence of the German people against this was no fault of their own, for becoming an adversary of the Nazi state was basically signing your own death certificate. It would take people in the political class to do what they could for the Jewish people they could help. And in some cases, they actually did. There probably would have been more open protests against what was happening to the Jewish people if, Clive James analyses, protests were not punished so severely. Axes and guillotines were routinely involved - a symbol from the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. Wow, I wonder why...

Clive James flops back to the 'jargon' of the text and has his way with the fact that there are important aspects still glossed over in the book he is reviewing even though, it is clear the majority of the review has been James talking about the Holocaust once again. The mention of many artistic people who did think the Jewish population were a worthy, intelligent audience of their work are rattled off: from Goethe (the great German poet) all the way down to the indecisive and horrible Wagner - there were many. Wagner is an ironic one because from what I know, he didn't like the Jews, but he didn't hate them either - yet Hitler seemed to absolutely adore Wagner. This also goes for Nietzsche. But the person who takes the cake here is Thomas Mann who had so much admiration for the Jews that he openly despised Hitler. James refers to Mann's 1936 essay where he parodies the Nazi logic of being anything but Jewish - it is a fantastic read.

"The novelist Joseph Roth drinking himself to death in Paris before the war, said that Hitler probably had the Christians in his sights too. We can never now trace the source of Hitler's passion for revenge but we can be reasonably certain that there would have been no satisfying it had he lived. Sooner or later, he would have got around to everybody."

No, no, no, I do not agree. When we look into the life and times of Adolf Hitler, we can definitely see the anti-Semitism in him. If he would have 'got around to everybody sooner or later' and nobody was opposing his killing of the Jews, what would have stopped him doing both at the same time if he wanted to? He was already killing Germans who were disabled or homosexual - and they were just Germans. Joseph Roth may have been a great literary mind but I think this analysis by Clive James is unfounded.

As the essay finishes, there is an analysis of the bloodstained 20th century from Hitler to Stalin to Mao and past. They are all one of the same and I honestly think that if Hitler did live past his time - someone would have taken him out. There were far too many people in his own country (and some in his own party) by the end of the war looking to do so.

Conclusion

I hope you've enjoyed reading this series. It has been a long one. If you have made it this far then I thank you and I hope you get your hands on a copy of this book!

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

I am:

🙋🏽♀️ Annie

📚 Avid Reader

📝 Reviewer and Commentator

🎓 Post-Grad Millennial (M.A)

***

I have:

📖 280K+ reads on Vocal

🫶🏼 Love for reading & research

🦋/X @AnnieWithBooks

***

🏡 UK

Comments (2)

nice

And there it is. When he goes off on certain misguided tangents, I want to slap him upside his privileged head. And I'm listening to Sir Ian Kershaw discuss Hitler on "The Rest is History" podcast, a real tonic to James' missteps. Thank you for this third take.