How the brain is organized

Big discoveries in studying the brain and other living things.

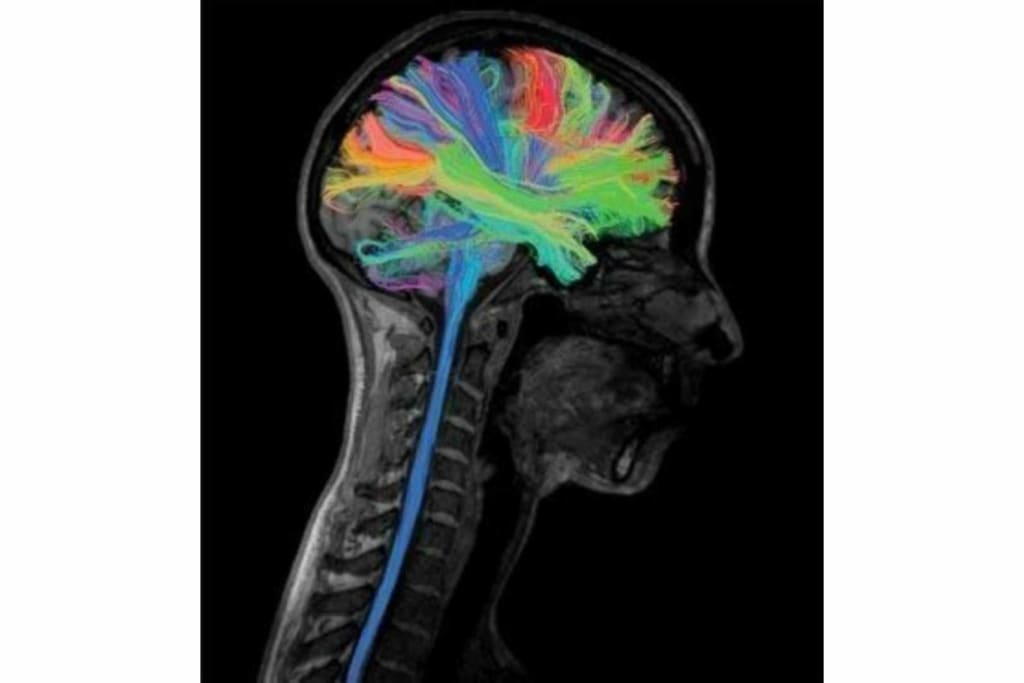

For centuries, medical experts and scientists have endeavored to unravel the enigmas concealed within the human brain. Questions about its organization, the allocation of various mental functions, and the intricate connections that give rise to our personal psychological experiences have captivated researchers. Over the past century, neuroscientists have assumed the role of map-makers, diligently delineating the brain's features and activities within well-defined parameters.

The prefrontal cortex is renowned as the locus of rationality, while the motor cortex orchestrates and coordinates movement. The somatosensory cortex and parietal lobes manage our perception of the physical world. Memories, language, and emotions find their processing hub in the temporal lobes, whereas the occipital lobe manages and integrates visual data. The cerebellum, in turn, executes the directives for bodily movements.

However, these distinctions arise from our culturally rooted beliefs about human nature. When scrutinizing brain segments to ascertain their functions, scientists often rely on their assumptions about the essence of the human mind, many of which can be traced back to ancient philosophers like Plato.

Recent investigations into cognitive brain functions, such as memory, have unveiled unexpected levels of overlap across various brain regions, to the extent that the conventional map and its rigid classifications lose their significance. Our current conceptualization of the mind does not neatly align with the functions of distinct brain systems. These categorizations are subjective and perhaps it's more prudent to examine the brain's organizational properties devoid of culturally biased categories.

Russell Poldrack, based at Stanford University, is spearheading this endeavor. Employing a computational approach, his lab is deciphering the organizing principles of the human mind. Through diverse psychological tasks, the lab gathers data to unveil the underlying structure. Machine learning is harnessed to identify neural activities related to memory recall. Remarkably, the data doesn't correlate solely with memory centers, but with broader activity constructs yet to be named. This revelation has prompted a reevaluation of our understanding of brain functions.

In the realm of neuroscience, a consensus is forming around the brain as a computational apparatus that necessitates understanding its computations. The challenge lies in explaining these computations, a task primarily relegated to the language of mathematics. This presents a quandary: will we craft models adept at predicting brain activity while remaining inscrutable to human comprehension?

Deep within Southeast Asia's jungles resides a peculiar flower, Rafflesia arnoldii, commonly known as the "corpse flower" due to its odor resembling decomposing flesh, attracting pollinating flies. This flower, the largest globally, transcends its floral identity to become a parasite, siphoning nutrients and water from other plants. This parasitic lifestyle results in the incorporation of genetic material from host plants into Rafflesia's genome, a phenomenon that may serve as a weapon to enhance its parasitic efficiency. Biologists have wrestled with decoding Rafflesia's complex genome due to its repetitive elements called transposons, which hinder traditional sequencing methods. Recent advancements, including bioinformatics, have facilitated the creation of a draft genome, revealing surprising insights. Nearly half of the conserved plant genes are absent in Rafflesia, signifying a paradigm-shifting discovery. Moreover, 90% of its genome consists of repeating DNA, defying norms. Though the reasons remain unknown, this revelation promises to reshape our understanding of parasite genomics and broaden our exploration of life's diverse manifestations.

In the early 20th century, sleep emerged as a focal point for researchers equipped with the electroencephalograph (EEG), a machine to measure brain electrical activity. Despite yielding valuable insights, this approach established a bias: viewing sleep as primarily neurological, centered in the brain. This perspective was challenged when simple organisms like cockroaches displayed sleep patterns, leading to the realization that sleep precedes complex brains. A groundbreaking discovery emerged when Japanese scientists observed that hydra, creatures with rudimentary nerve nets instead of brains, also exhibit sleep. This newfound evidence shifted the narrative, indicating that sleep evolved not solely for brain-related functions but primarily to regulate metabolism and facilitate repair processes. The evolving understanding suggests that sleep's impact extends beyond the brain and encompasses the broader organism's needs.

About the Creator

Earth Goings

This page covers current events on Earth, information and research about living organisms, and relatable topics.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.