4 Lost Letters Theodore Roosevelt Sent The Year He Died

Buried under 300,000 letters, these stood out

Theodore Roosevelt has been studied, analyzed, scrutinized, torn apart, and pieced back together in efficiently digestible works. Today, we look back on Roosevelt one 150 years later and marvel at the complexity of his life during his short time here on earth.

Historians continue to debate the consequences of his actions, moral integrity, and character of the man on the saddle. In one rein, you have Theodore, a loving father and husband, a dutiful citizen, an insatiable worker, a lover of nature, a multi-lingual man of culture, a student of science, and a champion for progress in the sense of women’s rights, labor laws, unions, conservation, and trust busting. Yet, on the hand holding the opposite rein, you have a man possessed by the glory of war, a man whose lust for a lasting legacy drove him to compromising situations, a man blinded by patriotism and unrelenting love of his nation, and a man who clashed with the indigenous people of the fledgling country.

As observers, researchers, and enthusiasts of history, we have to keep our moral relativism in check and ask ourselves a series of questions before we can rightfully learn from classical characters. Can we judge people of history based on our definition of morality? Can we separate modern ethics from actions of the past? Can we learn from their shortcomings? Should we detach morality from their actions and continue to teach lessons found in their motives? Should we embrace their morality and take lessons only from the good? Should we remember and teach only what we consider wrong? How and where we learn about historical characters changes our bias, so what better way to learn than from their own personal letters?

In 2019, Theodore's presidential archive of over 300,000 documents (by far the largest) was released to the public. I read over 10,000—all the letters he sent during the last year of his life—and transcribed the most interesting. I added some historical context to bring us back 1919 and give some color and life to the words behind the letters. I've also included the links to the letters themselves if you with to read them in the original type.

It's time to play the part of the historian and decide for yourself who Theodore Roosevelt was.

A Letter on Women's Suffrage

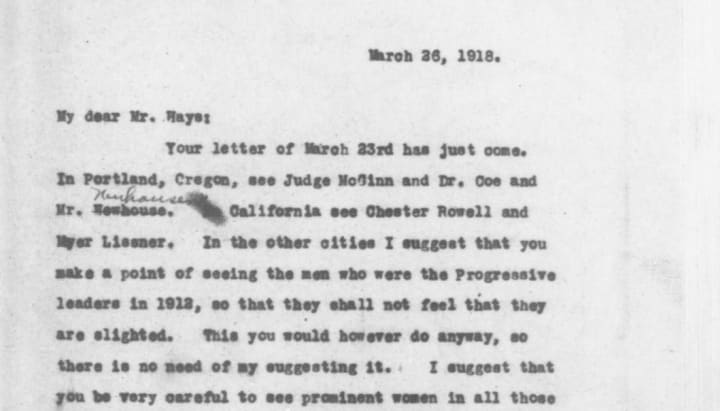

March 26, 1918.

Your letter of March 23rd has just come. In Portland, Oregon, see Judge McGinn and Dr. Coe and Mr. Newhouse. In California see Chester Rowell and Myer Lissner. In the other cities I suggest that you make a point of seeing the men who were the Progressive leaders in 1912, so that they shall not feel that they are slighted. This you would however do anyway, so there is no need of my suggesting it. I suggest that you be very careful to see prominent women in all those states. Personally I have found the women often like to be summoned together with the men, and some resent being called to a meeting by themselves. This is not an invariable rule, but I have found such a condition of mind so frequently that I venture to put you on your guard about it. It is perfectly true that the women are very apt to concentrate their attention purely on the suffrage issue and prohibition, and there is very real need that we should begin to take them in to [sic] our councils generally.

There is a special need for doing this in New York, where I do not think that our management at present is of the best and where the women offer a new and puzzling problem, with which old-style politicians are wholly incompetent to deal. That unhung traitor, Hearst, is an element of special danger in New York. The Vigilantes are anxious to do volunteer work against him and for us, although they usually keep clear partisan politics. I should like to introduce some of them to you when you come back.

Faithfully yours

Many letters from the last year of Theodore’s life relate to Women Suffrage, and the Suffragists. Interestingly, while in Harvard, Theodore’s senior thesis, "The Practicability of Equalizing Men and Women before the Law", was on the same subject some 40 years prior. Historians still wonder what prompted him to write such, at the time, a controversial thesis. He never mentioned it in his diary, nor anywhere else. Here are some excerpts:

“Viewed purely in the abstract, I think there can be no question that women should have equal rights with men. In the very large class of work which is purely mental… it is doubtful if women are inferior to men… individually many women are superior to the general run of men… if we could once thoroughly get rid of the feeling that an old maid is more to be looked down upon than an old bachelor, or that woman’s work, though equally good, should not be paid as well as man’s, we should have taken a long stride in advance… I contend that, even as the world now is, it is not only feasable [sic] but advisable to make women equal to men before the law.…”

A Rare Letter to FDR

May 6, 1918

Will you ask your Secretary to kindly return the papers of Joseph M. Henrickson, stepson of Dennis A. Janvrin, sent to you with a letter about this young man, in your reply to which, you advised that Hendrickson had been in an institution for the insane?

Sincerely yours,

One of Theodore’s greatest achievements was his defining role as Secretary of the Navy. It’s no mystery that future president and fifth cousin once-removed, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, would also aspire to the role. Of all people, Woodrow Wilson nominated FDR to the role who was confirmed unanimously by the Senate. In 1913, At 31, FDR became the youngest-ever Secretary of the Navy. War broke out in Europe a year later, and as Theodore had done during the beginnings of the Spanish American War, FDR jumped into the role of preparing for war. Theodore urged FDR to join the war efforts directly with his sons who were already scouting for opportunities to join the fighting. The department deemed that FDR’s position was too valuable to leave, so he stayed in Washington D.C. Years later, in 1918, FDR went overseas as a civilian to visit France during the war and came within one mile of the Germain line.

FDR followed very closely in Theodore’s political footsteps. They both graduated from Harvard, acted as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, were Governors of New York state, and ran for Vice President. FDR’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, was Theodore’s closest niece, and their relationship only grew after her father, and Theodore’s brother, Elliot, died. Theodore knew the young couple well and even stood in his brother’s place during their wedding. While Theodore didn’t write this letter, it should be noted that while the two men were close, it’s hard to say what their relationship was like towards the end of Theodore’s life. They each came from two wings of the Roosevelt family—Theodore’s aligning much closer to the Republican Party, and FDR to the Democratic Party. Naturally, this caused friction, which can already be felt here. Theodore typically jumps at the chance to write to family, but he seems content to let his secretary handle this correspondence.

A Letter to The Baron of Japan

My dear Baron Kaneko:

The enclosed letter and memorandum explain themselves. The memorandum will be no help to you. Personally I think the letter sets forth the fact as it is. There is no appropriate model for such a book as you contemplate. Personally I don’t recall a single life of an Emperor to which I would refer if I wanted, from a historian’s standpoint, information about his life! This may seem an extraordinary statement; but it is not, because Emperors are so important when they amount to anything at all that the life worth reading must necessarily be a study of all the social phenomins [sic] of their times. My dear Baron, instead of taking another book as a model, why don’t you deliberately start to write the model life yourself? I seriously believe that you can do it. No other Emperor in history saw his people pass through as extraordinary a transformation, and the account of the Emperor’s part in this transformation of his own life, and of the public life, of his great statesmen who were his servants, and of the people over whom he ruled, would be a work that would be a model for all time.

Faithfully yours,

Kaneko was a career statesman and diplomat of Japan. He was a vital component during the negotiations of the Russo-Japanese War nearly a decade before this letter was written. Kaneko requested that Roosevelt help Japan mediate a peace treaty with Russia, to which of course, Roosevelt accepted. Kaneko was a strong proponent of good diplomatic relations with the United States throughout his life, especially during the rising tide of Anti-American rhetoric from the Japanese government in the late 1930’s. He was one of the very few politicians in Japan to protest against war with the United States in 1941. Unfortunately for both nations, Kaneko died at the age of 89, in 1942, before peace could be seen between the two countries following World War II.

A Letter To His Dead Son’s Friend

Captain Philip Roosevelt,

My dear Phil:

Of course we are immensely pleased with your characteristic thoughtfulness in sending us the true copy of the award of the Croiz de Guerre to Quentin. I shall show it to Flora very soon. I hope you will soon be home. Your cousin Edith and I, when the time comes, intend to go abroad and mark Quentin’s grave with a small stone. Mrs. Coolidge wishes Ham Coolidge buried beside him, and so do we. But it may be a year before we go over, for I wish to avoid the crowd of fussy people and morbid people who are already beseeching to go to France.

Ever yours,

P.S.

I need largely say how very proud we are of your Croix de Guerre. No one more empathetically earned it. Inflammatory rheumatism accounts for the pencil.

Ham, or Hamilton Coolidge was the great-great-great grandson of United States President Thomas Jefferson. He was best friends with Quentin Roosevelt, TR’s son, who had just been shot down behind enemy lines. Quentin remains the only son of a presiden who was killed in combat. Hamilton was twenty-three years old when he was shot down by German anti-aircraft shells. With eight confirmed kills, he was considered a great pilot and promoted to Captain on October 3. He died twenty-five days later.

Together, Ham and Quentin attended Groton School, Harvard, and flight school. They served with the 1st Pursuit Group in France.

In a letter, dated August 11th, 1918, Ham wrote, “I took a motorcycle to look for Quentin’s grave. Well, what do you know . . . in passing through a small village all shot to pieces, I suddenly saw Rose Peabody walking down the street! You can imagine the surprise of meeting her. Gosh it was swell! It turned out that her mobile hospital was located there. Then on to look for poor Q.’s grave which had been reported but never officially confirmed to be at Chamery. I can say that, as it was published in all the papers. After scouting around for a while we finally found it near the town. The Americans had fixed up his grave decently. It had a plain wooden cross, but there was a little fence around the grave and some wildflower upon it. Nearby were a few charred remains of his machine where it fell, and a hole some three feet deep which it had dug into the ground where it had crashed. Nonie, that’s what makes an impression on one in this war. Bursting shrapnel, onion rockets, machine gun bullets and Boche planes give you a start at first, but you get used to all that. What you can never get used to, though, is to have your very best friends “go West”.

If you want to dig through the letters yourself, you can find the complete collection at the Library of Congress.

About the Creator

Alex Moliski

Full-time writer slinging sentences in the outdoor industry. When I'm not skiing, hiking, or climbing, I'm working with words. IG: @alexmoliski

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.