The Tasmanian Tiger’s DNA Reveals a Hidden Extinction Story

What ancient genetic weaknesses and human pressures combined to wipe out one of nature’s most mysterious predators

The thylacine, often called the Tasmanian tiger because of its striped back, was a unique carnivorous marsupial. It looked like a dog with a pouch and once roamed across Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. Sadly, the species was declared extinct in 1936, when the last known thylacine died in Hobart Zoo.

For a long time, people blamed its disappearance almost entirely on human actions. Bounty hunting in the 1800s and early 1900s wiped out large numbers, while habitat destruction and competition with dingoes made survival even harder. But new research shows the story is more complicated. The thylacine may have been struggling long before people arrived, due to genetic weaknesses that made it especially vulnerable.

Ancient Weaknesses in the DNA

In recent years, scientists have turned to the thylacine’s DNA for answers. In 2017, researchers managed to sequence its genome using a preserved pouch young specimen. What they found was striking: the species had very low genetic diversity, meaning individuals were too genetically similar to one another. This problem likely began 70,000 to 120,000 years ago, during the Ice Age. Such low diversity made the species less adaptable, more prone to disease, and less able to cope with sudden environmental shifts. This discovery suggested the thylacine was already fragile long before humans entered the picture. The seeds of its extinction had been planted thousands of years earlier.

A Deeper Look into Lost Genes

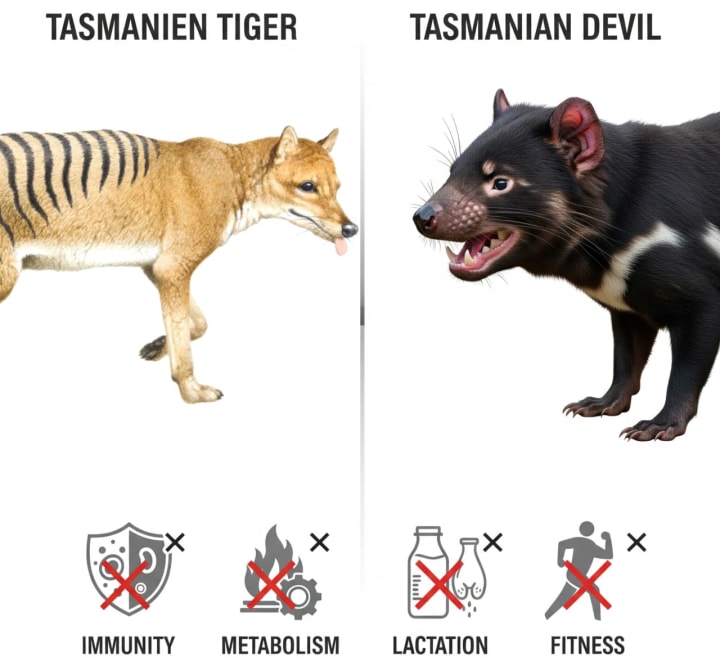

A new 2025 study dug even deeper into the thylacine’s genetic history. Using machine learning and comparisons with other marsupials like the Tasmanian devil, researchers discovered that the thylacine had lost four important genes sometime between 13 million and 1 million years ago. These genes SAMD9L, HSD17B13, CUZD1, and VWA7 played roles in immunity, metabolism, lactation, and overall health.

The absence of these genes may have been linked to the thylacine’s evolution into a hypercarnivore, meaning it relied almost entirely on meat for survival. While this shift made sense in its ancient environment, it also left the species less resilient. Interestingly, the Tasmanian devil, which survived despite facing similar pressures, still carries these genes perhaps giving it an edge.

Senses, Hunting, and Survival

The study also revealed that the thylacine had fewer olfactory receptor genes and a smaller olfactory lobe in its brain. In simple terms, it didn’t depend much on smell for hunting. Instead, it probably relied more on sharp eyesight and hearing. While this might have been fine in earlier times, it may have become a disadvantage later when prey grew scarce and habitats fragmented.

Disease and Human Pressure

Historical reports suggest that thylacines may have also suffered from disease. In the early 1900s, observers described a “distemper-like” illness sweeping through populations. Without strong immune genes like SAMD9L, the animals might have been especially vulnerable. Still, disease alone wasn’t enough to cause extinction. Combined with hunting, competition from dingoes, and shrinking habitats, it was the final blow.

Lessons for Today

The story of the thylacine is not just about what happened in the past. It also provides lessons for the future. By showing how long-term genetic weaknesses contributed to its downfall, scientists emphasize the importance of monitoring genetic health in endangered animals. For example, the Tasmanian devil today suffers from a contagious cancer known as facial tumor disease, and understanding its genetic resilience is vital to saving it.

The thylacine’s DNA has also sparked debate around de-extinction. Some companies, like Colossal Biosciences, are working on reconstructing its genome to explore the possibility of bringing it back. But whether we should do that is another question, as ethical and ecological concerns remain.

A Complex Extinction Story

The extinction of the thylacine is often seen as a simple case of humans driving a species to disappearance. But its genome tells a deeper story. Ancient genetic bottlenecks, lost genes, disease vulnerability, and ecological changes all combined with human pressure to seal its fate. This reminds us that extinction is rarely caused by one factor alone. It is often the result of multiple stresses building up over time. And it highlights why protecting biodiversity today means not just saving animals from hunting or habitat loss, but also paying close attention to their genetic health.

About the Creator

Muzamil khan

🔬✨ I simplify science & tech, turning complex ideas into engaging reads. 📚 Sometimes, I weave short stories that spark curiosity & imagination. 🚀💡 Facts meet creativity here!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.