The ideal spot for the first human settlers to dwell on Mars has been discovered by scientists.

Examining the volcanic plains of Mars

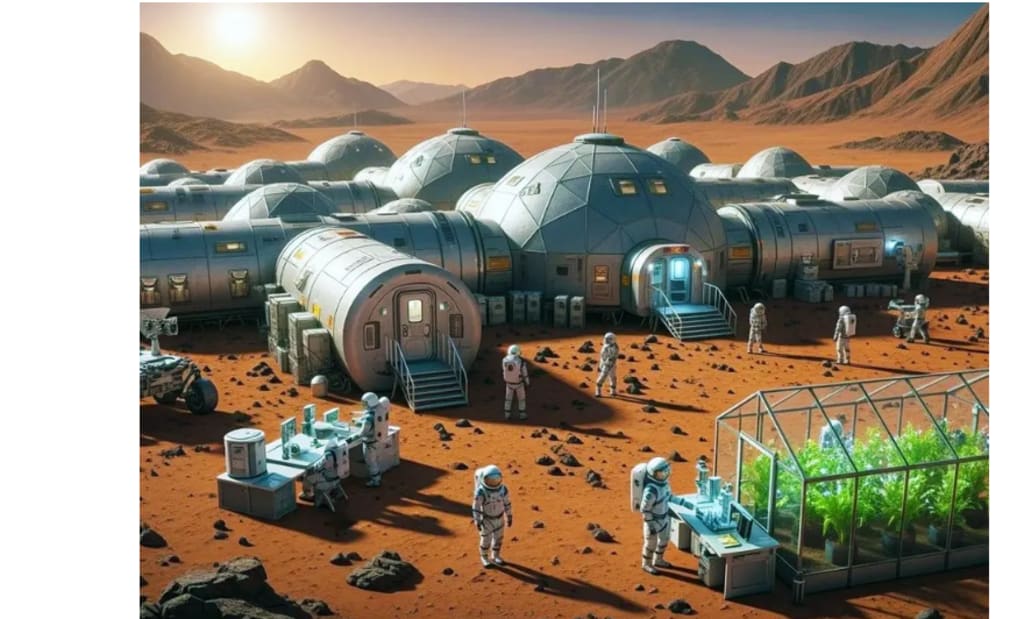

It will take more than just curiosity and bravery for the first astronauts to set foot on the surface of Mars. For breathing, drinking, growing food, and even producing rocket fuel for the journey home, they will require an abundance of water.

According to a recent study headed by planetary geologist Erica Luzzi of the University of Mississippi, there may be ice beneath the dusty soil in a stretch of terrain in the mid-latitudes of Mars.

Examining the volcanic plains of Mars

Amazonis Planitia is a wide volcanic plain that spans the planet's equator and poles. Luzzi and his colleagues studied it using incredibly sharp images taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's HiRISE camera.

The images showed distinctive textures that are frequently sculpted by ground ice on Earth, such as bright-rimmed, fresh-looking craters, polygonal fracture patterns, and faint undulations.

According to the data, there may be pockets of water ice less than a metre below the surface, which would be shallow enough for future astronauts or robotic drills without the need for bulky equipment.

Ice that astronauts could access

Survival and self-sufficiency are two interrelated reasons why the discovery is important. "H2O is essential if we are to send humans to Mars—not just for drinking, but also for propellant and a variety of other uses," Luzzi said.

The cost of missions would be unaffordable if those tonnes of water were transported from Earth. To reduce launch bulk and cost, planners intend to use in situ resource utilisation, or ISRU, which involves utilising local resources.

Large ice deposits are known to exist on Mars at high latitudes, particularly close to the poles. However, those regions are unsuitable for solar-powered surface bases due to their extreme cold and lack of sunlight.

Temperatures and light levels rise close to the equator, yet the ice retreats several meters below the surface. On the other hand, Amazonis Planitia is located in the climate sweet spot.

According to Luzzi, the mid-latitudes provide the ideal balance since they receive enough sunlight to generate electricity while being sufficiently cold to maintain ice close to the surface. "They are therefore perfect for landing sites in the future."

Using the air to map Mars

The High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, or HiRISE, is capable of identifying things on Mars that are only 30 centimetres across. Luzzi's team found small, well-defined impact craters in its photos that seem to have once held brilliant material before rapidly darkening.

Lander has verified that such brilliant layers are ice in other regions of Mars. Additionally, the researchers observed patterned ground, which resembled permafrost areas in Alaska and Siberia and consisted of networks of fissures and polygons.

The scientists also noticed "brain terrain," which are multi-mile hummocks that suggest subterranean ice that expands and contracts in response to seasonal warming and cooling.

In order to support their argument, the researchers charted how these structures are concentrated in shady hollows and on mild slopes, where ice may remain for millions of years despite Mars' thin, dry atmosphere.

The scientists came to the conclusion that there is probably accessible ice on Amazonis Planitia that is appropriate for ISRU; this idea will now be given more weight on NASA's list of potential landing sites.

How astronauts make it through Mars

The numbers are intimidating for engineers preparing a crewed mission. Throughout a 500-day stay, even a small expedition of four astronauts might need more than 20 tonnes of water. It would require additional launch ships and astronomical expenditures to carry that from Earth.

While tropical ice is deep or rare, polar ice is plentiful yet cold and black. A shovel's depth away, however, mid-latitude ice might be the magic bullet. By drawing a comparison between Mars logistics and lunar missions, Italian Space Agency scientist Giacomo Nodjoumi highlighted the stakes.

Going back and forth to Earth for replenishment would take us around a week for the moon, according to Nodjoumi. However, it would take months for Mars. Therefore, we need to be ready for prolonged periods without receiving supplies from Earth.

Water to drink and oxygen to breathe are the most vital resources. Our candidate landing site is really promising because of this.

Life may be preserved by ice.

More than just thirsty astronauts are interested in water ice; it may hold traces of ancient or even modern life.

According to Luzzi, "this also has astrobiological implications." On Earth, ice can support microbial colonies and preserve traces of extinct life. Therefore, it might reveal whether Mars was once habitable.

Scientists could examine trapped gases or organic molecules that have been protected from intense surface radiation by having access to relatively pure ice.

Confirming the frigid promise of Mars

Robotic scouts need to confirm the team's understanding before boots may start crushing Amazonian dust. To determine the thickness and continuity of the buried ice, Luzzi suggests using orbital radar sounders, such as the SHARAD on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter or the upcoming ESA-NASA Mars Ice Mapper.

"To better understand the depth and patchiness of the ice, radar analyses would be the next step," she stated. Whether the ice survives or sublimates away could depend on changes in the "lag deposit," a protective coating of rock and soil on top of the ice. "Knowing that will assist us in determining the appropriate landing location for a robotic precursor."

In the end, the material will need to be directly sampled by a rover or lander fitted with a drill and spectrometers. Without a rover, a lander, or a person to conduct accurate measurements, we can never be certain of anything. We won't know for sure until we get there and measure it," Nodjoumi stated.

Taking the initial steps

Even though it will still be ten or more years before humans can walk across the Red Planet, each new dataset helps to improve the map of potential habitats.

Luzzi and his colleagues have set a tempting target for mission planners by highlighting a neighbourhood where life-giving water is located only a few feet below the surface. Additionally, they have reminded the rest of us that Mars is not a desolate wasteland.

For those who are willing to dig, vital resources and possibly hints of past or present life can be found beneath its arid plains.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.