The Coolest Star in the Universe: WISE 1828+2650, the “Room-Temperature” Star

Space

When we think of a star, we imagine something blazing hot — a roaring sphere of plasma like our Sun, burning at thousands of degrees and flooding space with light. But the cosmos loves to challenge our assumptions. Somewhere out there, about 40 light-years away, floats a celestial oddball that defies everything we expect from a “star.”

Its name? WISE 1828+2650.

Its temperature? A cozy 25 °C (77 °F) — about the same as a pleasant summer afternoon on Earth.

Yes, you read that right: a star-like object as warm as your living room.

Not Quite a Star — Not Quite a Planet

Despite its official-sounding name, WISE 1828+2650 isn’t a normal star. It’s what astronomers call a brown dwarf — sometimes described as a “failed star.” Brown dwarfs form like stars, from collapsing clouds of gas and dust, but they never gain enough mass to ignite nuclear fusion in their cores.

Fusion — the process that powers true stars — is what makes the Sun shine. Without it, brown dwarfs don’t blaze; they merely glow faintly in infrared light, slowly radiating away the heat left over from their formation.

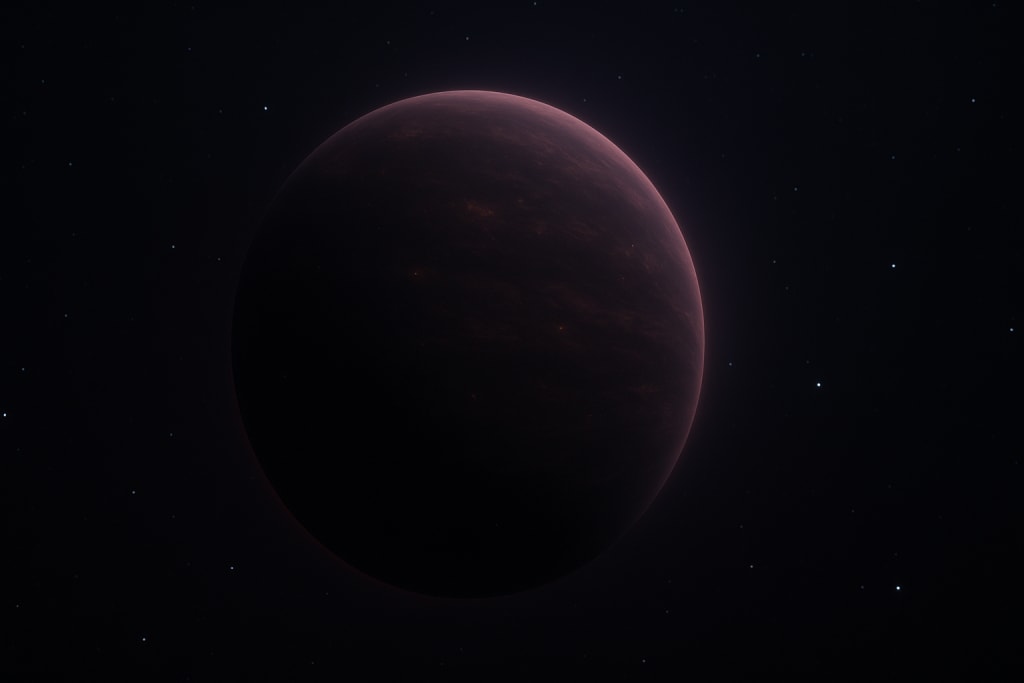

That means if you could somehow visit WISE 1828+2650, you wouldn’t see a fiery sun lighting up the sky. Instead, you’d find a dim, purplish-brown globe, radiating a gentle warmth and almost invisible to the human eye. It’s more like a cosmic ember than a torch.

The Coolest “Star” Ever Found

Astronomers discovered WISE 1828+2650 in 2011 using NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) — a space telescope designed to map the entire sky in infrared wavelengths. The object quickly earned fame as the coldest star-like body ever detected.

To put its chill in perspective:

- The surface of the Sun burns at around 5,500 °C (9,900 °F).

- A typical brown dwarf ranges between 1,000 and 2,500 °C (1,800–4,500 °F).

- But WISE 1828+2650? Just 25 °C (77 °F) — warm enough to support liquid water, if there were any.

That’s astonishing. We’re talking about an object technically classified as a “star,” yet no hotter than a cup of coffee.

A Star You Could Almost Touch

Imagine holding your hand a few meters above the surface of WISE 1828+2650. You wouldn’t feel blistering heat or searing radiation — you’d feel mild warmth, perhaps like standing near a campfire after it’s nearly gone out. Its atmosphere is thought to contain methane, ammonia, and water vapor, similar to that of Jupiter or Saturn.

In fact, WISE 1828+2650 has much in common with gas giants. It’s only about three to ten times the mass of Jupiter, which puts it right at the fuzzy boundary between “planet” and “star.” Astronomers classify such ultra-cool brown dwarfs as Y-dwarfs, the chilliest known class in the stellar family.

If Jupiter were just a bit heavier — enough to spark even weak fusion — it might look a lot like this.

A Neighbor in the Cosmic Backyard

At about 40 light-years away, WISE 1828+2650 isn’t exactly next door, but in cosmic terms, that’s relatively close. For comparison, the center of our galaxy is 26,000 light-years away. Yet, despite its proximity, this “star” is so faint that even powerful telescopes struggle to see it in visible light. It’s practically invisible — a ghost star hiding in the infrared.

That’s what makes it fascinating: it shows that the universe around us may be teeming with unseen, cold objects drifting quietly between the stars. Some astronomers suspect there could be billions of brown dwarfs in our galaxy, invisible to optical telescopes but glowing faintly in infrared.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, a “lukewarm star” might seem like a cosmic curiosity. But WISE 1828+2650 helps scientists answer some of astronomy’s biggest questions:

- How small can a star be before it stops being a star?

- How do planets and stars actually form from the same clouds of gas?

- What are the atmospheres of exoplanets really like?

By studying ultra-cool brown dwarfs, astronomers can refine models of planetary atmospheres, particularly for gas giants and potentially habitable exoplanets. The chemistry of these dim objects — rich in water vapor and methane — closely mirrors what we expect on distant worlds orbiting other stars.

In other words, studying WISE 1828+2650 isn’t just about learning how cold a star can get; it’s about learning how planets and stars connect in the grand story of cosmic evolution.

A Star You Could Almost Visit — But Not Live On

If you could somehow fly to WISE 1828+2650, you’d arrive at a place unlike anything in our solar system. The sky would be dim and rust-colored, the horizon bathed in faint infrared glow. You could stand (with a very good spacesuit) in its weak gravity and feel the ghostly warmth of a star that never quite came to life.

No daylight, no sunshine — just endless twilight under a sky full of distant, true stars.

The Warm Heart of a Cold Universe

WISE 1828+2650 reminds us that the universe isn’t just made of blazing suns and frozen voids. It’s full of in-between things — quiet, mysterious worlds that blur the boundaries between categories we thought were clear.

A star that’s room temperature may sound impossible, but it exists — and it’s teaching us that even in the coldest corners of space, warmth still glows softly in the dark.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.