New Discoveries in the TRAPPIST-1 and LHS 1140 Systems: Rethinking What “Habitable” Really Means

Space

For decades, the dream of discovering a second Earth has driven astronomers to peer deep into the cosmos, searching for rocky planets orbiting distant stars. Two of the most intriguing targets in that quest—TRAPPIST-1 and LHS 1140—have recently revealed surprising new details thanks to observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These discoveries are changing how scientists think about habitability, atmosphere loss, and what a truly “Earth-like” world might be.

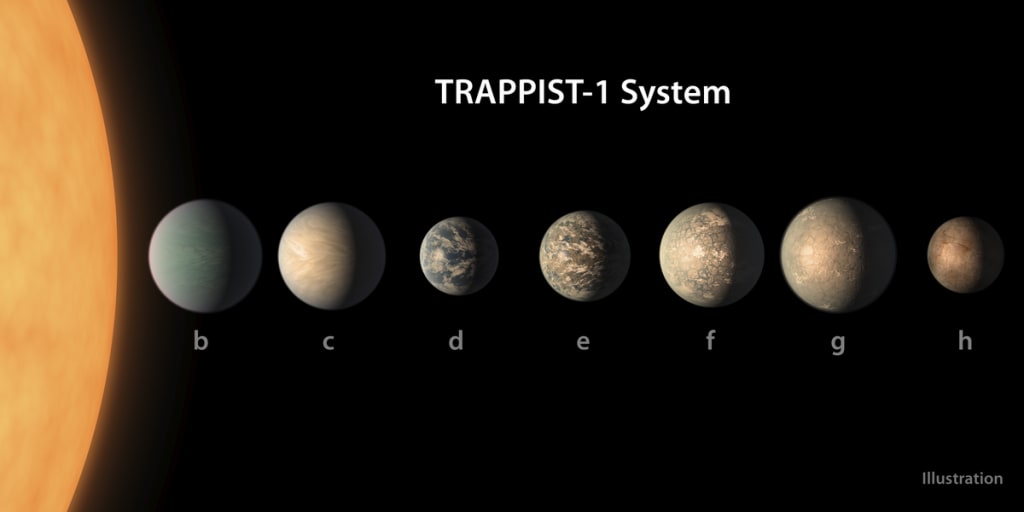

The TRAPPIST-1 System: Seven Small Worlds, One Big Question

Discovered in 2017, TRAPPIST-1 immediately captured the imagination of both scientists and the public. This ultra-cool red dwarf star, located about 40 light-years from Earth, hosts seven rocky planets—each roughly the size of our own. Three of them lie within the star’s habitable zone, where surface temperatures could, in theory, allow liquid water to exist.

It sounded like science fiction turned real: seven “Earths” orbiting one faint, red sun. Yet as astronomers began to study the system more closely, reality proved more complicated.

Losing Their Breath

Recent observations from the JWST have given us the clearest look yet at the atmospheres—or lack thereof—of these planets. In particular, TRAPPIST-1 e, once hailed as the best candidate for habitability, now seems unlikely to have a thick, hydrogen-helium atmosphere. Webb’s infrared data showed no sign of such gases, ruling out the possibility of a puffy, mini-Neptune-style world.

That might sound discouraging, but it’s actually exciting. A lack of hydrogen and helium could mean TRAPPIST-1 e has a denser, secondary atmosphere—something more like Earth’s mix of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Unfortunately, so far, even that kind of atmosphere hasn’t been confirmed. The spectra are largely flat, suggesting either an atmosphere too thin to detect or a bare, rocky surface directly exposed to starlight.

Another planet, TRAPPIST-1 d, shows similar results: no significant atmosphere detected. That finding raises a tough question—how do these planets, located right in the so-called “Goldilocks zone,” end up nearly airless?

The Angry Red Dwarf Problem

The answer likely lies in the star itself. TRAPPIST-1 is a small, dim red dwarf, but it’s also highly active, emitting frequent flares and bursts of radiation that can strip away a planet’s atmosphere over time. While this stellar violence makes for spectacular astrophysics, it’s bad news for surface life.

Still, researchers haven’t given up on the system. There’s a possibility that one or more planets could hold onto a thin secondary atmosphere, perhaps protected by magnetic fields or replenished by volcanic activity. Even a few hundred millibars of gas—about the pressure at the top of Mount Everest—could allow for fascinating climates and maybe even patches of surface water. The search continues.

The LHS 1140 System: The Rise of the “Eyeball World”

If TRAPPIST-1 represents the fragility of planetary atmospheres, LHS 1140 b represents resilience. Located about 49 light-years away in the constellation Cetus, this planet orbits another red dwarf star—but under conditions that appear more forgiving.

LHS 1140 b is a super-Earth, roughly 1.7 times Earth’s radius and about seven times its mass. It sits squarely in the habitable zone, and new JWST data suggest it might be one of the most promising worlds for life yet discovered.

A World of Water and Ice

Earlier studies left open the question of whether LHS 1140 b was a rocky planet or a “mini-Neptune” wrapped in a thick hydrogen envelope. The latest observations, however, indicate something much more intriguing: its density is too low for pure rock, suggesting that up to 20 percent of its mass could be water.

In other words, LHS 1140 b could be an ocean world—a massive sphere of rock and water with an atmosphere rich in nitrogen. Because it likely rotates synchronously (keeping one side always facing its star), scientists think it might resemble an “eyeball planet”: a globe with one oceanic, sunlit hemisphere surrounded by a ring of ice, while the far side remains locked in eternal darkness.

Clues in the Air

JWST’s early spectroscopy hints at a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, somewhat similar to Earth’s. If confirmed, that would be a breakthrough: a dense, stable atmosphere around a super-Earth in the habitable zone of a red dwarf. Such a world could maintain a warm region with liquid water under a relatively calm star—precisely the recipe astrobiologists have been hoping to find.

For now, the evidence remains preliminary. But as new data accumulate, LHS 1140 b is quickly becoming a poster child for next-generation habitability studies.

A Tale of Two Systems

Comparing TRAPPIST-1 and LHS 1140 is like comparing two chapters of the same cosmic story.

Feature TRAPPIST-1 e LHS 1140 b

Distance 40 light-years 49 light-years

Star Type Ultra-cool red dwarf Mid-M red dwarf

Atmosphere None detected; Likely nitrogen-rich,

possibly thin secondary Earth-like

Water Potential Uncertain Strong possibility of vast

oceans

Habitability Challenged by stellar flares More stable,

promising candidate

Together, they remind us that habitability is not a single checklist of conditions—it’s a dynamic balance between stellar activity, atmospheric chemistry, and planetary evolution. TRAPPIST-1’s planets may have lost their air to their tempestuous star, while LHS 1140 b seems to have found a delicate equilibrium.

Redefining the “Habitable Zone”

These discoveries are forcing scientists to rethink what the phrase “habitable zone” actually means. It’s no longer enough for a planet to simply sit at the right distance from its star. We must also ask:

- Can it hold onto its atmosphere?

- How active is its star?

- Is there a mechanism—like volcanism or magnetic protection—that helps sustain surface conditions?

The truth may be that many worlds once thought uninhabitable could, under the right circumstances, support life in forms very different from our own.

Looking Ahead

In the next few years, JWST and upcoming missions like the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) will continue to probe the atmospheres of both TRAPPIST-1’s planets and LHS 1140 b with even greater precision. Each new spectrum brings us closer to answering humanity’s oldest question: Are we alone?

And perhaps, when we finally do find that faint chemical fingerprint of life—oxygen, methane, or something entirely unexpected—it won’t be on a planet that looks like Earth at all. It might be on a dim, ice-rimmed “eyeball world,” orbiting a quiet red star 49 light-years away.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.