Space Junk: How a Tiny Screw Can Shatter a Satellite

Space

High above our planet, thousands of satellites orbit Earth — connecting phones, tracking storms, and streaming your favorite shows. But along with this incredible network of technology comes a growing hazard that few of us think about: space junk.

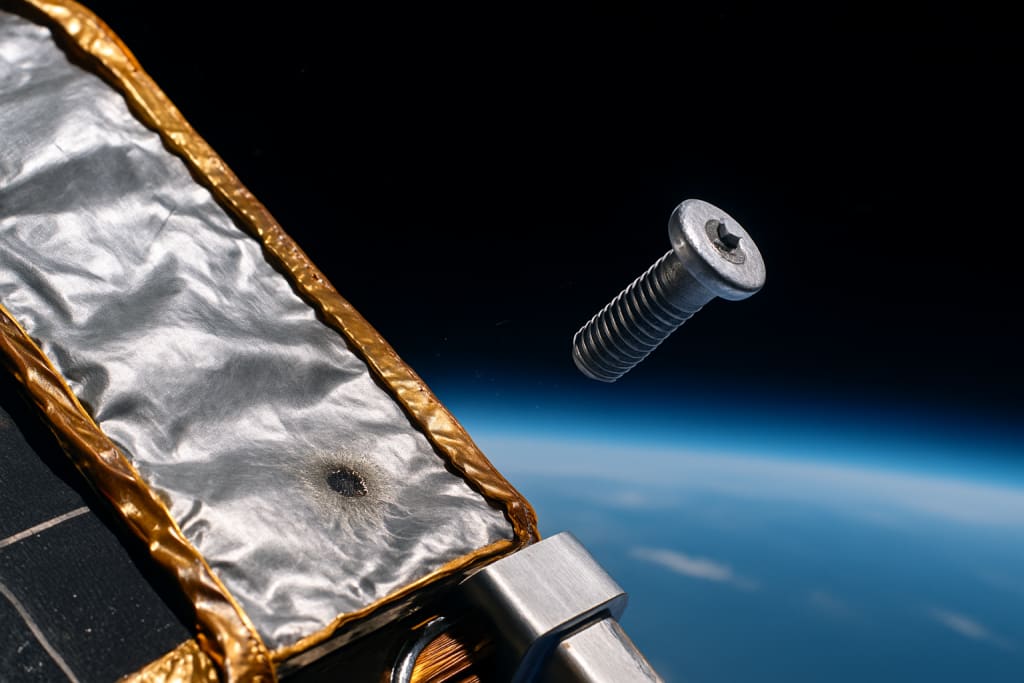

From shattered solar panels to paint flakes and lost bolts, millions of fragments now circle the planet at mind-boggling speeds. The most chilling part? Even a screw the size of a walnut could destroy a satellite in an instant.

Faster Than a Bullet

Objects in low-Earth orbit zip around the planet at 7 to 8 kilometers per second — roughly ten times faster than a speeding bullet. At that velocity, a piece of metal weighing just a few grams carries as much kinetic energy as a high-explosive shell.

Imagine tossing a pebble into a window at that speed — it wouldn’t just crack the glass; it would blow a hole right through it. The same physics applies to spacecraft. A tiny, untracked piece of debris can pierce a satellite’s body, rip through electronics, or puncture life-support modules.

In 2016, astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) found a small crater on one of its windows. The culprit? Likely a flake of paint — a particle barely visible to the naked eye. The incident was harmless but deeply unsettling. If something that small can dent reinforced glass, what could a metal nut do?

Where Does All This Junk Come From?

The space age has been roaring since 1957, when Sputnik first beeped over our heads. In the decades since, we’ve launched thousands of rockets and spacecraft — and not all of them came home.

Every launch leaves behind leftovers:

- Expended rocket stages;

- Defunct satellites drifting without control;

- Shrapnel from explosions or collisions;

- Even lost tools and bolts from spacewalks.

Today, agencies like NASA and the European Space Agency estimate there are over 36,000 trackable objects larger than 10 centimeters and hundreds of millions of smaller particles that radar can’t even detect. Each one is a potential bullet.

The Domino Effect: Kessler Syndrome

Here’s where things get really scary. When two objects collide in orbit, they break apart — and those fragments can strike other satellites, which then shatter into even more debris.

This chain reaction is known as the Kessler Syndrome, named after NASA scientist Donald Kessler, who first described it in 1978.

If it ever spirals out of control, the space around Earth could become so cluttered with debris that future launches — and even human spaceflight — might become impossible for decades. A single catastrophic collision could trigger thousands of new projectiles, turning Earth’s orbit into a shooting gallery.

A Real-World Example: Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251

In 2009, an American communications satellite, Iridium 33, smashed into a defunct Russian satellite, Cosmos 2251, at nearly 42,000 kilometers per hour. The impact obliterated both spacecraft and created over 2,000 pieces of debris large enough to track — and countless smaller ones that still pose a threat today.

That one crash alone increased the amount of dangerous junk in orbit by more than 10%.

How We’re Fighting Back

Cleaning up space is no easy feat — there’s no “vacuum cleaner” for orbit. But engineers around the world are testing bold solutions:

- Harpoons and nets: The European Space Agency’s ClearSpace-1 mission aims to capture defunct satellites and drag them down into the atmosphere, where they’ll burn up harmlessly.

- Lasers and tethers: Some concepts propose using ground-based lasers to nudge small debris out of orbit, or electromagnetic tethers to slow down dead satellites.

- Self-disposal systems: New spacecraft are designed to deorbit themselves after completing their missions, either by using built-in thrusters or by deploying drag sails that let atmospheric friction do the work.

On the policy side, international agreements now encourage operators to remove spacecraft from orbit within 25 years of mission end. But compliance is uneven, and commercial launches are booming — which means the junk problem is still growing.

The Hidden Mirror of Our Planet

Ultimately, the space-junk crisis reflects a familiar pattern: humanity’s tendency to expand first and clean up later.

Just as plastic fills the oceans and smog clouds the skies, debris now pollutes the vacuum beyond Earth. The difference is that in orbit, even the tiniest fragment can be lethal — and collisions can multiply exponentially.

The good news? Awareness is rising. Engineers, policymakers, and scientists are treating orbital debris as the urgent environmental issue it truly is. Because the night sky isn’t just a backdrop for technology — it’s a shared, fragile frontier.

If we want to keep exploring, we’ll have to do what we’ve long postponed on Earth: learn to clean up after ourselves — before the heavens get too crowded for us to look up in wonder.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.