Seth stares at me across his desk.

I wish he’d blink. He reminds me of a moose solving a riddle.

But I feel for him. I’d look that same if I heard what I just said to him, my business partner of 33 years.

We started our company back in 2112. We’ve done well by any standard. Our timing couldn’t have been better for the technology we offered.

But things sometimes change. And they did last night.

***

I sat on the side of the bed. A small light glowed from the hallway.

“How did they see what happened?” Samuel, my 10 year-old grandson, asks. Always curious, that boy. From birth.

“When people talk about ‘organic memory’, that’s what they mean,” I answered. “You’ve heard that term, Mule? Organic memory?” He nods, so I go on. “People used their eyes and minds and bodies to get information to their brains, and their brains would record their lives. Their brain took in all the images, stored them, organized them, and managed them, sometimes randomly bringing up sadness or joy or heartbreak or anxiety or any experience floating around. Sort of a haphazard and unreliable method.”

He scanned the room for any sense in that idea. “But did their CIUs help them?” he wonders. CIUs - that is, Cerebral Implanted Units, and pronounced ‘see-yous’ to finish the clumsily dweeby tech joke - are surgical implants that became all but mandatory between 2110 and 2118 to help us all indoctrinate equitably and ensure agreement on reality and history. The truth is that they’ve never been legally mandatory. But fat chance you’ll get work or find much, if any, social acceptance or the slightest trust without one.

Mule’s brown eyes are riveted, bright in their darkness, taking in my words and my every twitch. The tiny lens of his CIU is also unblinking, just beside his left eye. His curiosity coupled with his imagination often leaks into the cracks in a given thought, maybe even to just fill the fissure, but eventually expands, and splits the structure of an idea. And he doesn’t let go, remaining stubborn until it happens. His will not be an easy life in these times. But it’s a secret side-reason my nickname for him is Mule.

“CIUs weren’t around yet,” I say. “People had to remember things, and picture them in their brain.” I pause. I was in the last demographic that widely used organic memory before CIUs arrived, something that had already culturally atrophied by then thanks to the gradual, then total reliance on ubiquitous video for damned near everything. “Even before I was born,” I continue, “the early internet started people using video and sharing it. A lot. And images, whether from screens or brains, stir emotions. Gradually, over a long time, video became the language everyone used. But back then, it collided with the video in people’s brains. Sorting emotions became more impossible. Emotions are kind of what rule people, then and now. That created confusion inside people. So it didn’t…”

“How did they learn things if they didn’t get the teachings through their CIUs?” Mule interrupts.

Now I have the saucer-eyes. “Oo. That’s a big question,” I say, contorting my face to consider the deep, dark hole I know this is. He’s only 10, but he is 10 which is a good time to have The Talk, as we call it. I just try to lay some groundwork, a stone or two. “Well,” I begin, “people used to make mistakes to learn. I know that sounds like a completely weird contradiction. You know what a contradiction is, right?” He nods, and I finish. “But it’s the only way they did learn, really.”

“But if they made mistakes, that would’ve proved that they didn’t learn,” he says.

“Right,” I answer, “but they had to go through the mistake, then learn - or not, and go through the mistake again until they did learn. Or sometimes never learn. Over and over.” I trail off because I feel shifty, the logic sounds circular, even evasive. Then an echo hums in my chest, a memory from space. This still happens sometimes - dormant blips from outside the solar system of my mind hit in holograms of my memory’s younger, buff self before they evaporate. This one is the sparking elation of the day of finding balance on a hover bike for the first time, my scab-crusts from the falls just barely beginning to flake off. The wind in my face blasted me with love for the world. It was the same day the Pythagorean theorem sank in for good. It was a fucking good day.

Mule had sat up at my last sentence in horrified wonder. Not the sleepytime story I’d anticipated. “Oh, my,” he says in a rapt whisper, “That sounds like torture.”

“It does,” I say, “to us. But it worked. It was awful. But it was amazing. Because even though it was messy, it let everyone learn when they were ready.” I stop before I said, and when it did happen, it felt like nothing else.

I kiss his forehead, though he’s nowhere near sleep - his capsule of an hour ago ineffectual. “Lay back down,” I say. “I’ll sit with you here. We’ll be quiet and you’ll go to sleep. Otherwise your mom will never let me put you to bed again.”

“You tell the best stories, Papa,” he says.

I smile a smile he can’t see and stroke the kiss spot. I button it with, “Let’s talk about all this again tomorrow.” My eyes have adjusted enough to see his face sending a faint glow. I recognize a piece of my own face in his eyes and cheekbones. As he gets older, his jaw is approaching mine. And I feel the flood of something beyond thoughts or emotion like I used to. Years, decades ago, I perceived a thread that runs through us all, back to our parents and beyond, and forward through our kids and beyond. It’s one of those things for which there’s no evidence, no fair description, and no way to communicate, but came with having a child. You inherit a knowing that you can share with someone who’s had that experience, with no words, just by a quick exchange of a glance and smile. But now, reminded by Mule’s resting face, I’ve come to believe that a thread is insufficient. He and I and my father and my son are the same. The same material. The same energy. Tangible and otherwise. In him, I am. And in me, he is.

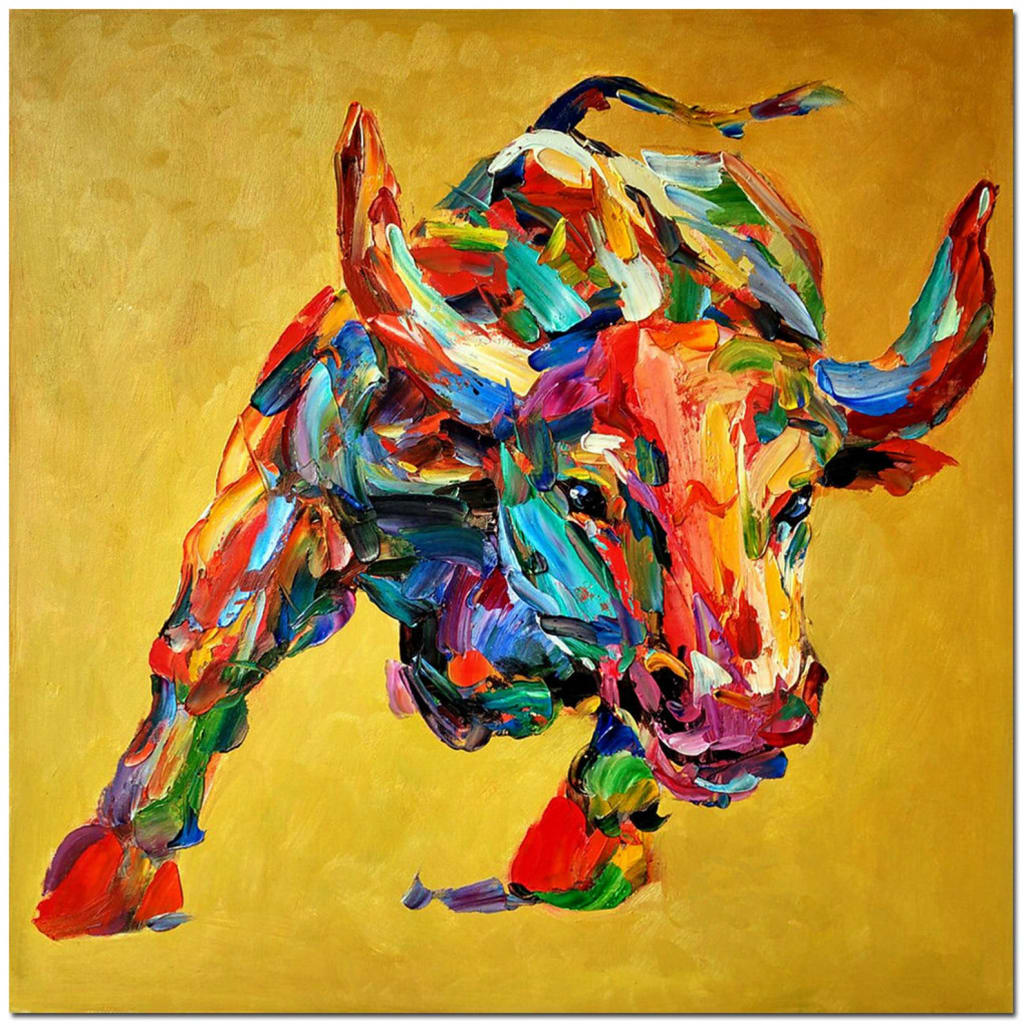

Unannounced, the thoughts of my dad waltz through my mind’s doorway. My father died when I was 3. He was from the town we lived, in what used to be Nebraska. Every two years, there’d be a rodeo revival in Ogallala to bask in arcane tradition. The story goes that he was bull riding and, at the end of a successful ride, was thrown against the metal gate that had swung loose. He was gone immediately, his brain dented and scrambled. There’s likely video of it, but I’ve never sought it out. My own images have always been enough. Quite possibly gentler. And those images were not a small reason I ran the other way to become an enigma: a massively successful techie from Ogallala. When I was about 7, we began frequenting a Mexican restaurant in town. On our maiden visit, we were sat at a table below a picture - an old oil painting of a writhing or dancing bull - open to interpretation - in a fit of fury or celebration. I knew the picture wasn’t alive, but seemed a hair’s breadth away from that spark. I must have looked at it over a hundred times during that hour, alternating between hypnotized and wary, a glance or trance. For years afterward when we visited, I’d never let the painting out of my sight, positioning myself for easy peeks. The bull’s face was expressionless (tough to tell what or when a bull is thinking), but was not without an inner life. In fact, it was a sort of brilliant artistic illusion that’d provoke the observer - in this case, me - to slide deep into its imaginary life and history, sometimes ferocious, sometimes holding an important message. If up to me, the painting should’ve been in the Louvre. There was a connection between us, me and this bull. I wondered if my father was trying to send a message through him, his adversary and killer and last one in contact. I imagined it possible the bull welcomed the role as a penance. I was both terrified and magnetically pulled to it, and was each meal there to have my eyes and dreams get lost in the sharp, crude knife strokes of color.

With my eyes still closed, sitting next to Mule’s slumber, I watch my own theater. It takes over. My Mexican bull, more vivacious than ever, appears, stops, and looks at me, the breath out of his dilated nostrils taking on the sound of Mule’s kid-snore. Then Mule’s face appears next to him, like the bull is a pet, looking different somehow. Then I see it. Mule’s without his CIU. I startle back to the room from the half-sleep.

My bull has finally sent me a message.

I barely sleep until morning.

***

The next day, this day, dawns.

“I’m sorry, Seth,” I say. “I’m out.” “But why,” Seth begins then stops, for a moment returning to the perplexed moose.

“Why now?” he asks, not for an answer, but more to stumble as a man to regain his bearing. “Are you okay?”

“I am. I’m fine, thanks.” I’m searching too, and let him know. “I don’t know. I’m just not sure of what we’re doing. What I’m doing.”

“We’re doing what we always wanted to do,” Seth says. “Since we were in school.” He looks around the room and back to me. “This is all of what we hoped for.”

“True,” I agree. “It is. But we grow, get old, and sometimes change. What I hope for may be different now. And what we’re a part of, the technology, the CIU that we make a component for - it’s so big and unstoppable and raging. I can’t change that. But I have to stop. I’m jumping off that bull, and it may be painful when I hit the ground.” But I’m getting off on my terms.” I don’t explain the metaphor, and he doesn’t ask. We sit.

Eventually, I’ll walk out.

Right now, I’m content to be sitting in the dirt. And thinking of Mule.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.