A Monster's Memories

As recorded on hotel stationery

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me man? Did I solicit thee from darkness to promote me? —John Milton, Paradise Lost

The question isn’t “What do we want to know about people?” It's "What do people want to tell us about themselves?" —Mark Zuckerberg

Imagine waking up in a place you've never been, in a body not your own.

This was the case for me once, famously. But the sensation of late has been nearly inescapable. So frequent are these bouts of amnesia that it is only with the greatest reluctance that I withdraw from the succor of sleep at all; I am loathe to trade my nocturnal phantasms, however terrifying they may sometimes be, for a reality which will scarcely bear my reckoning. So, each dawn, I weigh anchor off the coast of Morpheus’ realm with the heavy heart and slow step of a sailor bound for regions both unknown and unknowable.

That’s what happened this morning, at any rate. I was wrestling with a half-remembered nymph in an embrace too mutually satisfying to qualify as ravishment, yet too violent, perhaps, to be entirely consensual— I dreamt, you see, and in dreams all things are permitted— when, at the very brink of carnal epiphany, I felt my hold on unconsciousness slipping. Like a drowning man clutching a greased buoy I struggled to forestall my immersion in the waking world... but, alas, to no avail. All vestiges of my fleeting pleasure vanished and, though my eyes remained tightly shut, I was now aware of an entire substratum of sound that permeated the space in which I slept.

Closest to hand was an insistent, droning noise overlying a dull clatter, not unlike that made by a basket of bones. Turning my head to one side, I slowly opened my eyes with an inexplicable sense of dread. What manner of scientific perversion or instrument of torture was this squat white sarcophagus, groaning and rattling at my bedside? It had a name, of that I was certain, but one which might elude me indefinitely, in my present agitated condition.

Next came a murmur of voices, so faint yet so near they could be emanating from somewhere within my head. Enveloped in the pure sweat of fear, I strained to make sense of the intruders’ words, wondering whether they had yet perceived that I was awake. I heard a string of deprecations, directed at whom I could not say, followed by a harsh peal of laughter. Unable to restrain myself any longer, I twisted my neck violently to confront my persecutors, only to find the dim bedchamber unpopulated, apart from my tormented self. Not far from my pillow, however, a small black box was the evident source of this disembodied gibbering.

A large glowing portal opposite my bed provided the sole illumination here; across its surface played a phantasmagoria of mostly incomprehensible images. The effect was quite hypnotic, and for some time I remained content to rest my eyes upon these visions, like one of Plato’s cave dwellers who has suddenly wrenched his attention from shadow play in order to confront the very flames that animate his existence. Not only was I ignorant of where I was, or who I was; at that moment, I had no real sense even of what I was. The whole concept of being a man— or a monster, for that matter— was well beyond me in this enchanted state.

Some shrouded recess of my brain guided me suddenly to my feet, in response to an urgent pain in the region of my groin. In the half-light of an adjacent room, I discerned various porcelain fixtures; intuitively, I grasped the flaccid organ between my legs and relieved myself in one of them. Thus disburdened, I retraced my steps and attempted to take stock of my environment; the room was small and unattractive, with little in the way of decor, save a framed print above my headboard. I studied this unremarkable seascape at some length, as if it might offer some clue as to my whereabouts, then cautiously attempted to lift a curtain from the window-- I let it fall at once, repelled by the shard of sunlight which pierced my vision. At length making my way to the unadorned mirror bolted to the wall above the bureau, I was simultaneously fascinated and repelled by the prospect of regarding my own visage.

Somewhat to my surprise, the planes of my face were not all that displeasing, despite the discolorations and prominent scarring, though there was something about their sheen and symmetry which struck me as unnatural. I flexed the muscles beneath my skin and contorted my features. I pouted in mock sadness and leered hideously, very nearly amusing myself when suddenly— there! Good God! For a split second it was as if my flesh had melted away to reveal, beneath the mask of humanity, the terrible mutant countenance of pure evil. I recoiled from my own features as I would from a serpent and, simultaneously, was assaulted by a shrill ringing in my ears, so startling that for a moment I feared my heart would seize up in my chest.

Reeling, I confronted the apparatus on my bedside table which was the source of the painful and recurring noise. Though my first instinct was to dash it to pieces, I possessed a dim recollection of a more practical method for silencing the thing. I picked up the device and held it to my ear. There came an anodyne voice from somewhere in the ether: “Wake up call.”

In an instant, as I hung up what I now knew to be a telephone, my senses were flooded with the sudden, gratifying recognition of my mundane surroundings; the rattling box by my bedside was merely an air conditioner, the ongoing cacophony could be attributed to the fact that I had left both the radio and television on-- the latter was broadcasting mundane images of a hotel lobby, as I had decided to forego the purchase of any further pornography. (Alas, I fear my passion for revisiting Plutarch's Lives or The Sorrows of Young Werther may cool considerably with the ready availability of such entertainment.) Also, it now dawned on me that not long ago I had urinated in the bathtub.

Most important, however, was my realization that I had finally escaped my most recent captors and was sitting in an inn, not far from the coast of the northwestern United States, the selfsame inn I presently occupy as I set these thoughts down on paper. How long ago seems the tortured journey which brought me here; the thawing of the glaciers which brought my existence to the attention of those Arctic scientists (all due thanks to a phenomenon described as “global warming”); my subsequent revival by medical researchers; and my desperate and far from bloodless escape, armed only with my wits, superhuman strength and stolen papers which now identify me as one Seth Hoffman.

Gentle reader, I know thee not. Perhaps these words are meant for mine eyes alone. But I beseech thee Mnemosyne, mother of Muses, to assist me in this chronicle for, along with periods of disorientation like the one just described, I have begun to suffer from sudden random recollections, which afflict me almost like seizures. I will call to mind some insignificant slight in a Genevese tavern and burn with a nearly homicidal rage, regardless of the fact that the incident in question took place over one hundred and seventy-five years ago. Or I will find myself in near paroxysms of happiness, recalling an all too fleeting moment of joy at a fairground or brothel. But I fear I am losing the ability to organize these impressions in a coherent fashion. Such is the capricious nature of memory, planting flags here and there in the vast arctic wasteland of our consciousness, while around these poles the remainder of our experiences, our fleeting fancies and quotidian dreams, all quite simply melt away-- you know it, oh reader, dear stranger, this sense of eternal dissolution, you’ll know it even as you read these words should you, for just a moment, close your eyes and attempt to recall how this very sentence began…

How I digress. I confess to a fleeting distraction, in the form of the remarkable device found amongst Mr. Hoffman’s personal possessions, tucked within an otherwise unremarkable valise. I have seen it before, and heard it described as a “laptop computer.” (Such things were ubiquitous amongst the staff at McMurdo Station.) I am and have always been a rapid learner. Having brought the device to life, I find myself quite fascinated by the panoply of entertainments afforded by what I believe is known as the information superhighway. But I must return to the task at hand, for who knows how much longer it will be within my powers to do so?

Given my nefarious past, not to mention the fantastic nature of my very existence, the fact that I'm in a position to indulge in these recollections at all must be accounted something of a miracle. But where to begin my tale? With my nascence, in Bavaria, in 1789? Or my unholy resurrection, a quarter century later? For, truth be told, I have lived three lives thus far: the first was my natural allotment; then came the strange afterlife with which the Doctor cursed me; and now this resurrection, long after my mortal coil should have been shed with some finality.

Certainly, the momentary terror I experienced in my hotel room this morning was but a taste of that ordeal I underwent more than two centuries ago, as my second life was beginning. I could no more recollect just how it commenced, than I could my actual moment of birth. Like an infant, or the universe should it possess a consciousness, I suddenly, simply realized I existed, with absolutely no sense of when that existence began, nor what could possibly have preceded it. If I might embellish the simile a bit further, in the earliest days I would liken myself to an infant born in a charnel house, insensate to the Gothic horror of his surroundings, preoccupied as the newborn is with the simple discovery of his own fingers and toes. Gradually, however, the cruel nature of my captivity became clear to me, and I began to make my displeasure felt during the Doctor's daily visits.

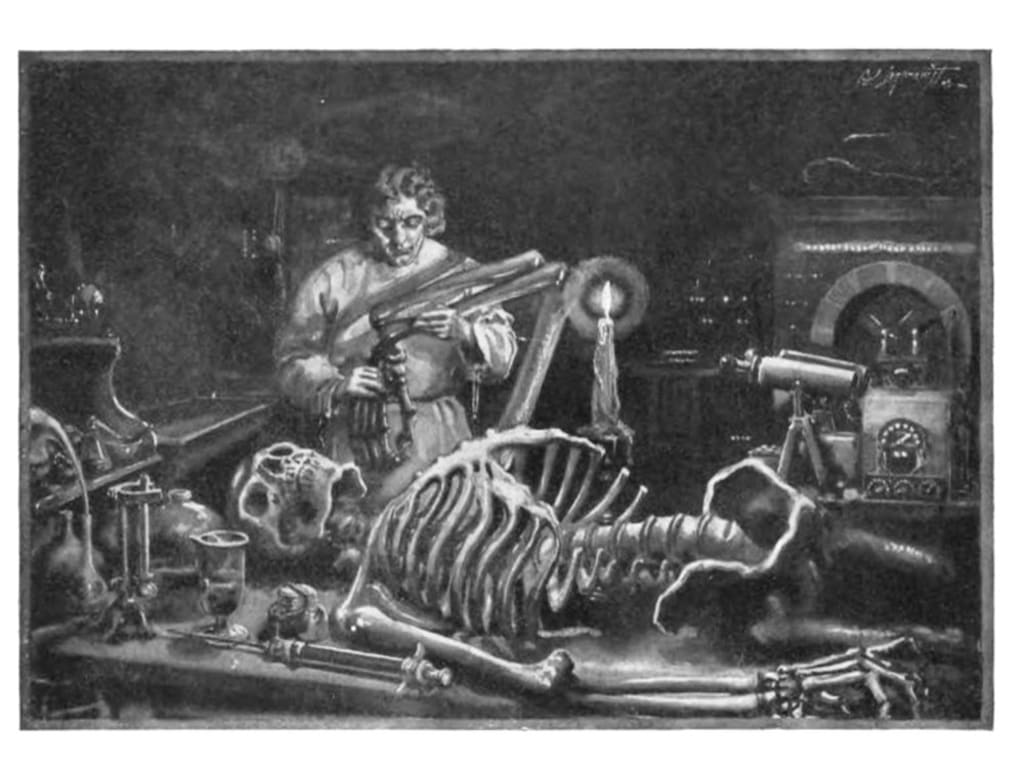

It was not necessary for the Doctor to imprison me-- my weak and useless limbs were shackles enough. There was an elaborate system of weights and pulleys in the candlelit cell which served as my cradle. An observer from, say, a human rights organization (had any existed at the time) would surely have assumed these were designed to inflict some hideous physical cruelty, but this was not the case. The Doctor was shockingly prescient in many respects, among them his anticipation of the intricate mechanics of the modern gymnasium-- he had constructed this device for the sole purpose of exercising my misshapen frame; for, though I possessed the stature of a giant, it harbored barely the strength of a kitten. In truth, given my debilitated state at that time, I'd have been handily overmatched by a particularly vicious cat. Thus, I eagerly anticipated our daily work-outs; they not only provided a break from the monotony of pondering the reason for my existence, but offered the prospect of freedom from the burden of my unwieldy body. The Doctor had to take care not to overexert my muscles during these sessions, as I never offered any protest; in fact, I was literally impervious to physical pain, though this wasn't entirely clear to me at the time.

"How do you feel?" the Doctor muttered, as he manipulated my left arm. The question was, by now, strictly rhetorical, I believe the Doctor had long since ceased to believe I would ever utter a sound, beyond the occasional incomprehensible grunt or cry of psychic agony. So try to imagine his surprise when, on this day, I finally answered him. The seeds which had planted themselves in my mind days earlier had slowly pushed their shoots through the fetid night soil of my consciousness to sprout on my tongue in the form of a few, barely audible, German syllables-- "Ich fühle mich wie der Tod.”

I feel like death.

The Doctor reacted as if bitten, starting away and allowing my arm to drop with a thud. He blinked several times, then composed himself, resuming his physical ministrations as if I'd told him exactly what he expected to hear. "Yes..." he said at length. "I suppose you would."

I wished to converse with him further, was in fact composing an eloquent entreaty in my mind even as he kneaded my bicep. But I was exhausted by the effort I had already expended, and further words remained as inaccessible to me as the revelations one experiences in a dream. Still, the crucial goal had been achieved. The Doctor now recognized that I was more than some insensate lump of flesh he had stitched together for reasons beyond fathoming. My mind yet functioned, I was capable of communicating with him. And now, during the long hours when I was deprived of his company, my mind turned inward. How could it not, when the only alternative was to confront the grotesque mockery of a human shell which it was now my misfortune to call home? Even in the earliest days of my reincarnation, that time of fear, confusion and utter mental anguish, I possessed an inchoate sense of the truth: before I was a monster, I was a man. But what manner of man was I?

What a great many friends Mr. Hoffman has! (Apologies, my attention has drifted once more to this amazing computing device.) I would not have thought it possible to be so well acquainted with so many hundreds of people. And the photographs they share! Delectable-looking foodstuffs, adorable children, beloved pets… clearly, this far-flung future to which I’ve found myself unwillingly transported is not the waking nightmare I once took it to be. Now where is it I’ve left off?

Oh yes, those endless nights in the prison of my flesh… at first, I concentrated on simply recalling my name. But even so basic a fact remained stubbornly beyond my awareness, till at length I allowed my concentration to lapse, opening myself to whatever impressions might form from the vapor of my frustration. It was then that the memories came staggering back, slowly, unsteadily, like crapulous libertines returning from a night's debauch.

"Hans." This was my name, I was sure of it, for I heard it in the mouth of my own father, my biological father, as opposed to the man who would claim a more unholy patrimony. And remembering my father, I suddenly remembered all things, encompassing even my tragic delivery into this vale of tears, at the outset of what was my first life. I must've heard the tale often enough to feel as though I'd been a detached observer on that accursed day, watching the midwife wrestle with the placenta that had nourished me but which now refused to join me in my liberation from the womb, the sanguineous ordeal coming to an end only with my poor mother's final breath. Moreover, I was not born like others; rather, it was as if the homunculus had failed to develop into a fetus at all, but had simply sprung from my mother’s loins, a foreshortened simulacrum of a human being. I was, in short, a dwarf. (The pun is admittedly regrettable.)

My father was rendered half-mad with grief-- but the remaining half was, I suspect, mad to begin with. As a young professor at the University of Ingolstadt, he had become involved in a somewhat mysterious fraternity; prior to my birth and the simultaneous death of my mother, the ideas espoused by this secret society, who playfully called themselves the Illuminati, were more or less airy abstractions to him. But as I grew older, my father determined to press me into service as an experimental subject, to illustrate the notions espoused by his fellow freethinkers. Not incidentally, it was through the Illuminati that my father became acquainted with the Doctor, clearly no stranger to perverse empiricism himself.

Upon thinking of my father, the first moment which comes to mind was the day he took me to a festival in Kelheim, to see a demonstration of the Mechanical Turk. The Turk was an astonishing automaton, evidently capable of rational thought, able to easily beat experienced players at chess. How I longed to test my own game against that of this miraculous machine! For, though my limbs might’ve been stunted, my stature unprepossessing, the Lord had compensated me with a brain of preternatural power, and the game of kings had fascinated me since my earliest childhood. It is this brain of mine which has allowed me to speak multiple languages fluently, and to adapt so quickly to this strange new world. It was also, I would come to learn, a brain which the Doctor desperately coveted.

In addition to the Turk, at the Kelheim festival I was privileged enough to observe, and even operate, one of the earliest typewriters. I find this skill serves me well now, as I continue to experiment with Hoffman’s extraordinary machine. Indeed, it would appear that most any combination of words I produce results in an instantaneous riot of images. This is an almost ungodly power! I must push my dark thoughts to one side, for fear of inadvertently summoning them into existence, and return at once to my narrative, which I continue to write by hand, on foolscap provided by this establishment, despite my dubious penmanship.

Eventually, of course, I was to learn that the Turk was a fraud, a magnificent one, but a fraud nonetheless. I discovered this was so when my father rented out my services to a competitor of Baron Wolfgang Von Kempelen, the Turk’s creator. The man who hired me, one Claude Beaufoy, possessed an automaton of his own, a Mechanical Frenchman, complete with highly articulated armature and handlebar mustache. It was immediately clear what my duties would be. As was the case with Von Kempelen’s creation, the Frenchman possessed an ingeniously hidden inner chamber, from which I would be able to control its movements like a puppeteer.

I bonded with Beaufoy, and would gladly have joined him on the Frenchman’s European tour. But alas, the money would prove insufficient for my father’s needs. When the Doctor approached him with a far more generous offer— to this day, I have no idea what sum of money ultimately changed hands— my father agreed to sell to him my most prized possession, the most prized possession of any man with a semblance of sanity.

My brain.

Of course, the folklore will have you believe that the source of this organ was the gibbet, or a defiled grave, its original provenance never to be known. Errant nonsense! The Doctor would scarcely have worked with the brain of a known criminal, and the procedure would’ve been impossible, in any event, if the key ingredient were allowed to deteriorate for any length of time.

No, there was no Burke and Hare brutality associated with the extraction of my cerebellum; I was most carefully murdered, my grey matter immediately put on ice. Further details, however, shall forever remain a mystery, because all records of the procedure were destroyed by this man I’ve called the Doctor, though popular culture has dubbed him Frankenstein. (The name means nothing to me. Mary Shelley penned her little "ghost story" based on the true facts as she'd heard them from Dr. John Polidori, but in the tradition of romans à clef, she wisely chose to change all appellations. I will practice similar discretion, for pragmatic reasons; I am guilty of some ghastly crimes and, though it's safe to say the statute of limitations may have run out on those which predate a mortal's lifespan, I wish to take no unnecessary chances.)

There is so much to tell. My vengeance upon the Doctor, my adventures on the ice, my rapid assimilation into this strange new society… all must be set down before… but first, I must follow up on an earlier avenue of investigation, a few suggestions submitted to the omniscient computer which have borne unexpected fruit. I blush to recount what those suggestions were— suffice it to say, I’d hoped to make up for the centuries of deprivation I’ve endured, where interactions with the fairer sex are concerned. The delay shouldn’t be significant, at which point I shall return to this journal…

Damn you, Chronos, what infernal trick have you employed! How can so much time have passed outside of my ken? The sun has vanished, my pursuers are pounding at the door, and I have prepared no viable means of escape. This uncanny chronicle shall certainly accompany me to whatever haven I seek next… as shall my newest traveling companion. How strange, this feeling that I, a profane creation of a brilliant, yet fundamentally unsound mind, should have so much in common with this deceptively simple-looking cabinet of infinite wonder.

But enough procrastination, my enemies are at the gate! Onward now, ever onward, into the gathering night!

About the Creator

Michael Ferris

Michael Ferris is a screenwriter, living in Los Angeles.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.