What is placebo therapy, and why is it used in clinical trials?

Unmasking the Power of Nothing: Placebo Therapy in Clinical Trials

Imagine taking a pill for pain, only to find out later it was just sugar. Strangely enough you still felt better. That’s not magic; it’s the placebo effect a fascinating way the mind can influence the body. Placebo therapy isn’t trickery. It’s actually a powerful tool in modern medicine that helps doctors test if treatments really work.

What is a placebo?

A placebo is something that looks like real treatment but has no active medicine in it like sugar pills, saltwater injections, or even pretend surgeries. The treatment itself doesn’t do anything. The real magic is in the placebo effect, where people feel better simply because they believe they’re being treated.

How does it work?

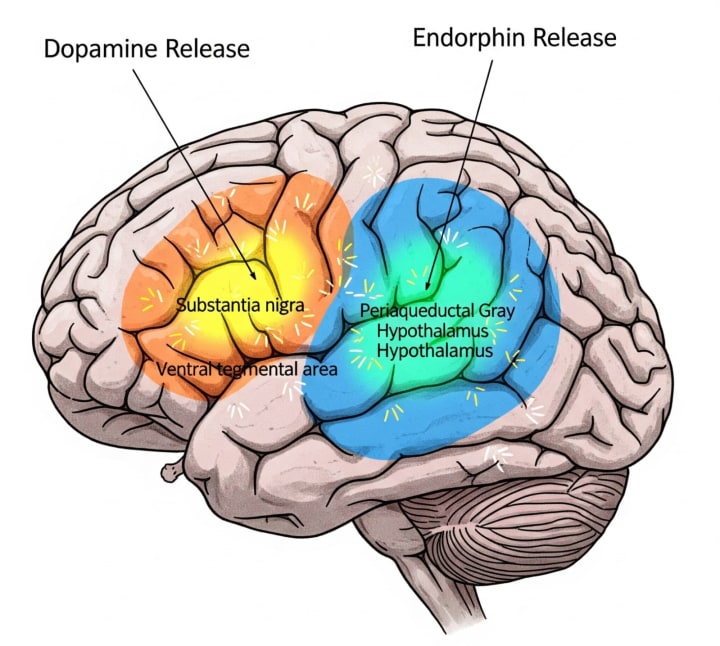

Science shows this effect is very real. Brain scans reveal that placebos can trigger the release of natural chemicals like endorphins (the body’s own painkillers) and dopamine (the “feel-good” chemical). For example, people with stomach issues have reported feeling better after knowingly taking a placebo pill proving it’s not just about being “tricked,” but about how the brain can heal itself. Doctors have noticed the placebo effect for centuries. In the 1700s, a doctor named John Haygarth proved that fake wooden tools worked as well as “miracle devices,” showing how much belief matters. But it was after World War II that placebos became an official part of medical research, helping scientists separate real cures from false ones.

Mechanisms behind the placebo effect

The placebo effect is not just “imaginary” it involves measurable biological and psychological processes:

- Expectation and Belief

-When someone believes a treatment will work, their brain anticipates improvement.

-This expectation triggers brain regions (like the prefrontal cortex) involved in prediction and reward.

-The brain then releases chemicals (such as endorphins and dopamine) that actually change the body’s state.

- Conditioning (Pavlovian response)

If a person has repeatedly taken a real medicine in the past and experienced relief, their body learns to associate the act of treatment with healing. Later, even a placebo can trigger the same physiological response because the body has been conditioned to “expect” improvement.

- Neurochemical Effects

-Pain relief (analgesia): Placebos can cause the release of endorphins (natural painkillers) and activate opioid receptors in the brain.

-Dopamine release: Placebos can increase dopamine in reward-related brain areas, improving mood and motivation (especially studied in Parkinson’s disease).

-Serotonin & other neurotransmitters: Placebos may also modulate other systems depending on the illness.

- Brain Network Activation

Brain imaging studies show that placebos affect:

-Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC): Processes pain and expectation.

-Prefrontal cortex: Involved in belief and decision-making.

-Nucleus accumbens: Reward and pleasure center, linked to dopamine release.

-Periaqueductal gray (PAG): A brainstem region that regulates pain via endorphins.

So, the brain isn’t “faking” improvement it’s activating real biological pathways.

- Stress Reduction & Immune Effects

-Belief in treatment lowers stress and anxiety, reducing levels of cortisol (a stress hormone).

-Lower stress can enhance immune function, speed up healing, and improve overall well-being.

-Studies even show changes in immune cell activity and inflammation levels with placebo treatments.

Nocebo Effect (the flip side)

If a person expects negative effects, a placebo can cause side effects headaches, nausea, or worsening symptoms even though nothing harmful was given. This is called the nocebo effect.

Why are placebos important in research?

When scientists test a new drug, they need to know if it truly works not just because people “think” it does. That’s where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) come in. Some patients get the real drug, others get a placebo that looks the same. If the real drug outperforms the placebo, then it’s considered effective.

To keep things fair, researchers use blinding:

In single-blind trials, patients don’t know what they’re taking.

In double-blind trials, neither patients nor doctors know.

In triple-blind trials, even the data analysts don’t know until the end.

This prevents bias and ensures results are trustworthy.

Are placebos always ethical?

This is tricky. Giving someone a placebo instead of real treatment can feel unfair especially in serious diseases. That’s why rules exist: placebos are only used when no proven treatment is available or when it’s safe to do so. Informed consent makes sure patients know they might receive one.

Real-world lessons

- In antidepressant trials, some drugs were found to work only slightly better than placebos, raising questions about overprescribing.

- In COVID-19 vaccine trials, placebos helped prove safety and effectiveness quickly.

- On the flip side, the nocebo effect shows how negative expectations can make people feel worse like when some vaccine side effects turned out to be linked more to fear than the vaccine itself.

So, next time you take a pill, remember sometimes, the biggest medicine might just be belief.

About the Creator

Muzamil khan

🔬✨ I simplify science & tech, turning complex ideas into engaging reads. 📚 Sometimes, I weave short stories that spark curiosity & imagination. 🚀💡 Facts meet creativity here!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.