The Titanic submersible

New update news on The submersible

What are submersibles?

Submersibles are small, limited range watercrafts designed for a set mission that are built to allow them to operate in a specific environment, according to maritime historian Salvatore Mercogliano. These vessels are typically able to be fully submerged into water and cruise using their own power supply and air renewal system.

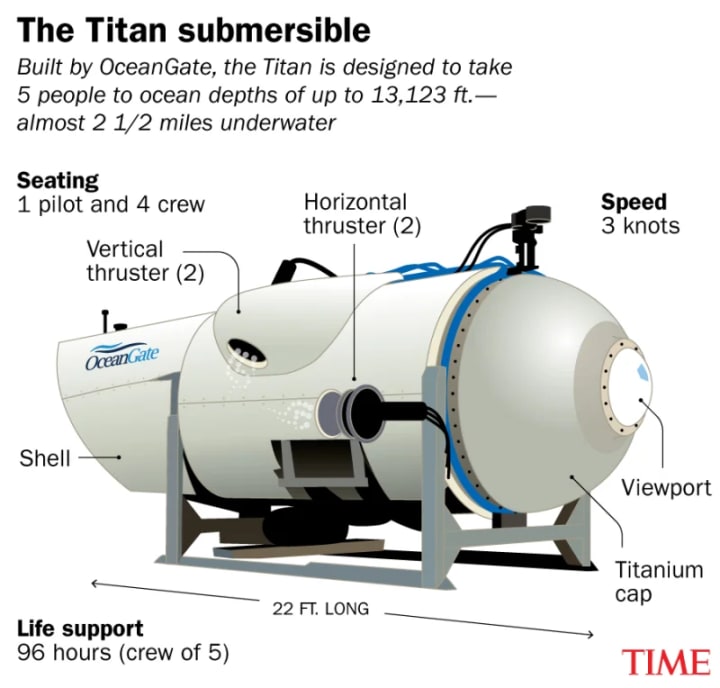

While some submersibles are remotely-operated—essentially manually controlled or programmed robots—these usually operate unmanned. Vessels like the missing Titan are known as human-occupied vehicles. The Titan was designed to transport five people to depths of around 2.4 miles in order to reach the Titanic shipwreck. It weighs around 11.5 tons and can also take on speeds of about 3 knots, or 3.4 miles per hour.

“It doesn’t have a lot of propulsion so it can’t sail great distances but it has just enough propulsion to sail and operate in and around the wreck and then come back to the surface,” Mercogliano told TIME.

What are the safety regulations in place for submersibles?

Typically, marine operators must seek to have vessels “classed” by an independent body. The process would involve examining the vessel according to stringent standards and ensuring that the designs are safe. However, the Titan has not been classed in this way. OceanGate said in a blog post in 2019 that it did not seek to class the Titan because the process “does not address the operational risks.”

Instead, the company claims that “no other submersible currently utilizes real-time monitoring to monitor hull heath during a dive,” and therefore the integrity of the hull is guaranteed on each dive. It is also regarded as an experimental vessel that Mercogliano says is not bound to any particular regulations.

“Since this vessel doesn’t operate in coastal waters, it’s actually out in international waters, so there’s literally no rules and regulations that are governing it,” he says. In a 2019 profile interview for Smithsonian magazine, Rush, OceanGate’s CEO, said that there had been no injuries in the commercial submersible field for decades. “It’s obscenely safe because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown—because they have all these regulations,” he said.

AD

But Mercogliano notes that any rules Rush may have been referring to would only apply if the vessel was in U.S. waters. “The submersible does not fly a flag, and it is not registered in any state or nation,” he said.

According to the New York Times, OceanGate was warned several times about potentially fatal outcomes of the expedition as early as January 2018, when experts became concerned about safety. The company’s own director of marine operations, David Lochridge, formulated a report that emphasized the “the potential dangers to passengers of the Titan as the submersible reached extreme depths.”

Additionally, as many as three dozen industry figures wrote a letter to Rush in March 2018, to voice their apprehension at the “experimental” approach OceanGate was using. The letter warned that the trip “could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.”What are the safety regulations in place for submersibles?

Typically, marine operators must seek to have vessels “classed” by an independent body. The process would involve examining the vessel according to stringent standards and ensuring that the designs are safe. However, the Titan has not been classed in this way. OceanGate said in a blog post in 2019 that it did not seek to class the Titan because the process “does not address the operational risks.”

Instead, the company claims that “no other submersible currently utilizes real-time monitoring to monitor hull heath during a dive,” and therefore the integrity of the hull is guaranteed on each dive. It is also regarded as an experimental vessel that Mercogliano says is not bound to any particular regulations.

“Since this vessel doesn’t operate in coastal waters, it’s actually out in international waters, so there’s literally no rules and regulations that are governing it,” he says. In a 2019 profile interview for Smithsonian magazine, Rush, OceanGate’s CEO, said that there had been no injuries in the commercial submersible field for decades. “It’s obscenely safe because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown—because they have all these regulations,” he said.

AD

But Mercogliano notes that any rules Rush may have been referring to would only apply if the vessel was in U.S. waters. “The submersible does not fly a flag, and it is not registered in any state or nation,” he said.

According to the New York Times, OceanGate was warned several times about potentially fatal outcomes of the expedition as early as January 2018, when experts became concerned about safety. The company’s own director of marine operations, David Lochridge, formulated a report that emphasized the “the potential dangers to passengers of the Titan as the submersible reached extreme depths.”

Additionally, as many as three dozen industry figures wrote a letter to Rush in March 2018, to voice their apprehension at the “experimental” approach OceanGate was using. The letter warned that the trip “could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.”

Finally according to the latest news the sumbersible was blevied to have been struck by alightning or hogh water wave deep from the atlantic ocean.

The USA coast guard say all the participants are dead

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.