The Structure and Layers of the Ocean Floor

Exploring the Composition and Topography of the Ocean Floor

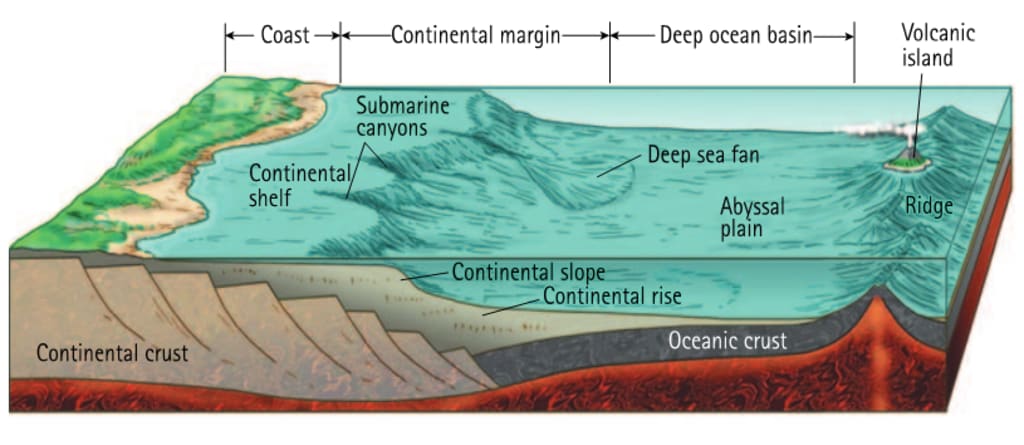

The ocean, covering over 70% of Earth’s surface, is a vast and mysterious realm. Beneath its surface lies the ocean floor—an intricate landscape that rivals the complexity of the continents. This underwater terrain is not flat or uniform, but composed of a variety of features shaped by geological processes over millions of years. Understanding the structure and layers of the ocean floor is crucial for marine science, geology, and environmental studies.

1. Introduction to the Ocean Floor

The ocean floor, or seabed, refers to the bottom of the ocean. Like the land we live on, it is part of the Earth’s crust, specifically the oceanic crust, which differs in composition and density from the continental crust. The oceanic crust is thinner and denser, primarily composed of basaltic rocks, whereas the continental crust is made up of granitic rocks.

The ocean floor is not a vast, flat expanse; it is a diverse and dynamic environment. From the shallow continental shelves to the deepest oceanic trenches, the seafloor consists of multiple structures and layers, each with its unique characteristics.

2. Major Features of the Ocean Floor

The ocean floor is composed of several key features:

a. Continental Shelf

The continental shelf is the extended perimeter of each continent, lying submerged under relatively shallow water. These shelves are biologically rich and are the locations of important fisheries. The slope is gentle and may extend hundreds of kilometers from the shore.

b. Continental Slope

Beyond the shelf lies the continental slope, a steeper incline that marks the boundary between continental and oceanic crust. This area often contains submarine canyons carved by underwater currents and sediment flows.

c. Continental Rise

At the base of the slope, the seafloor flattens out slightly in a region known as the continental rise. It consists of accumulated sediments that have cascaded down from the continental shelf and slope, forming thick layers over time.

d. Abyssal Plain

One of the flattest and smoothest regions on Earth, the abyssal plain lies beyond the continental rise. It is covered with fine-grained sediments and can reach depths of 3,000 to 6,000 meters. These plains make up the majority of the deep ocean floor.

e. Mid-Ocean Ridges

These underwater mountain ranges are created by tectonic activity where plates diverge, allowing magma to rise and form new crust. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is one of the most well-known examples. These ridges often have central rift valleys and hydrothermal vents.

f. Ocean Trenches

Trenches are the deepest parts of the ocean, formed at subduction zones where one tectonic plate is forced beneath another. The Mariana Trench in the western Pacific is the deepest known part of the Earth's seabed, reaching over 11,000 meters.

g. Seamounts and Guyots

Seamounts are underwater volcanic mountains. If a seamount becomes eroded and flat-topped, it is called a guyot. These formations often serve as habitats for diverse marine species.

3. Geological Layers of the Ocean Floor

The structure of the ocean floor can be broken down into several geological layers, from top to bottom:

a. Sediment Layer

The uppermost layer consists of sediments that accumulate from various sources, including eroded land materials, dead marine organisms, volcanic ash, and cosmic dust. These sediments vary in thickness and composition depending on location. For example, sediments are thicker near continents and thinner at mid-ocean ridges.

b. Basaltic Crust

Beneath the sediment layer lies the oceanic crust, composed primarily of basalt—a dark, fine-grained volcanic rock. This layer is about 5-10 kilometers thick and is created at mid-ocean ridges through volcanic activity.

c. Upper Mantle

Below the oceanic crust is the upper mantle, made up of peridotite and other dense, solid rocks. This layer is part of the lithosphere, which includes the crust and the rigid uppermost portion of the mantle. The lithosphere is broken into tectonic plates that float on the more ductile asthenosphere beneath.

4. Plate Tectonics and Ocean Floor Formation

The concept of plate tectonics is vital to understanding the structure of the ocean floor. The Earth's lithosphere is divided into several plates that move relative to each other. At divergent boundaries, plates move apart, creating mid-ocean ridges where new oceanic crust is formed. At convergent boundaries, one plate subducts beneath another, forming trenches and volcanic arcs.

These tectonic movements are responsible for shaping the ocean floor’s topography. Over millions of years, plates spread, collide, and slide past each other, continually renewing and transforming the seafloor.

5. Marine Life and the Ocean Floor

The physical structure of the ocean floor significantly affects marine life. Shallow areas like continental shelves support a wide range of species due to ample sunlight and nutrient availability. In contrast, the deep-sea environment, such as abyssal plains and trenches, is home to organisms adapted to high pressure, low temperatures, and darkness.

Hydrothermal vents, found near mid-ocean ridges, are hotspots of biodiversity. They release mineral-rich fluids that support unique ecosystems, including chemosynthetic bacteria and exotic creatures like giant tube worms.

6. Human Exploration and Technology

Exploring the ocean floor is a challenging task due to its inaccessibility and extreme conditions. However, advancements in technology have enabled significant discoveries. Tools like sonar mapping, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and deep-sea submersibles help scientists map and study the ocean floor in detail.

Satellite altimetry is also used to measure slight variations in sea surface height, which can indicate the presence of underwater mountains or trenches. Despite these advances, much of the ocean floor remains unexplored, making it one of the last frontiers on Earth.

7. Importance of Studying the Ocean Floor

Studying the structure and layers of the ocean floor is vital for multiple reasons:

Scientific Research: Understanding plate tectonics, earthquake activity, and geological history.

Environmental Monitoring: Assessing climate change impacts, such as sediment composition and sea-level rise.

Resource Exploration: Locating underwater resources like oil, gas, and minerals.

Biodiversity Conservation: Protecting unique deep-sea ecosystems from human exploitation.

8. Conclusion

The ocean floor is a complex and dynamic environment shaped by geological processes and home to diverse ecosystems. From the shallow continental shelves to the mysterious deep-sea trenches, every feature tells a story of Earth's evolution. Although modern technology has shed light on many of its secrets, vast areas remain unexplored. Continued exploration and study are essential for understanding our planet’s past, managing its resources, and protecting its marine life for future generations.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.