Rare Earth Elements and Sustainability: Balancing Industrial Demand with Environmental Impact

Assessing the Environmental Costs and Sustainable Solutions Behind High-Tech Materials

The global transition toward a carbon-neutral economy relies heavily on a specific group of minerals: Rare Earth Elements (REEs). These elements are the silent engines of the green revolution, powering everything from the permanent magnets in offshore wind turbines to the high-efficiency motors in electric propulsion systems. However, a profound ecological paradox lies at the heart of this transition. While REEs are essential for reducing global carbon emissions, their extraction and refinement processes present significant environmental and social challenges.

Achieving true sustainability requires a holistic evaluation of the REE lifecycle, ensuring that the pursuit of climate goals does not come at the cost of local ecosystems and community health.

The Chemical Drivers of Innovation

Rare earth elements consist of seventeen metallic elements, including the fifteen lanthanides plus scandium and yttrium. Despite their name, these elements are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust; however, they are rarely found in concentrated, exploitable seams, making their extraction technically demanding.

Their value lies in unique physical properties:

Magnetism: Elements like neodymium and dysprosium allow for the creation of powerful magnets that remain stable at high temperatures.

Luminescence: Europium and terbium are critical for energy-efficient lighting and display technologies.

Electrochemical Reactivity: Lanthanum is a core component in nickel-metal hydride batteries.

As the requirement for these technologies increases, the pressure on the natural environments where these minerals reside intensifies, necessitating a shift toward more responsible management practices.

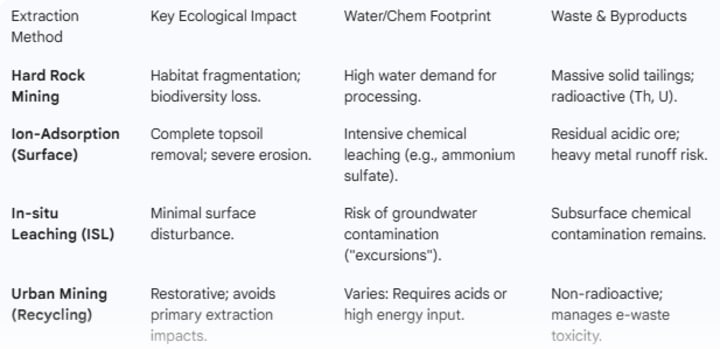

Comparative Environmental Impact of Extraction Methods

The primary sustainability challenge of REEs is not their scarcity, but the geochemical complexity of their processing. Unlike gold or iron, REEs are chemically similar to one another and are often bound up with radioactive materials.

The following table provides a comparative analysis of the primary extraction and recovery methods, highlighting their respective ecological footprints.

Ecological and Land Degradation Concerns

The physical footprint of REE extraction often results in severe habitat fragmentation. Open-pit mining requires the removal of vast tracts of vegetation, which can lead to:

Biodiversity Loss: The displacement of local flora and fauna, some of which may be endemic to the mining region.

Soil Fertility: Without the stabilizing influence of native plants, landscapes become prone to landslides and nutrient depletion.

Water Scarcity: The refinement of a single ton of rare earth oxide can require thousands of gallons of water, often in regions already facing significant water stress.

Targeted Mitigation Strategies

To address the impacts detailed above, the following sustainability-driven interventions are being prioritized by researchers and policy analysts:

Closed-Loop Hydrometallurgy: Implementing systems that recover and reuse chemical reagents, such as sulfuric acid and ammonia, to minimize the toxic load of effluent.

Phytoremediation: Utilizing specific plant species to stabilize and decontaminate soil in post-extraction sites, particularly in ion-adsorption clay regions.

Tailings Valorization: Investigating methods to convert mining waste into stable construction materials, thereby reducing the physical footprint of tailing ponds.

Bio-leaching: Exploring the use of organic acids produced by microorganisms as a lower-impact alternative to concentrated inorganic acids for the separation of lanthanides.

The Social and Ethical Dimensions of the Supply Chain

Sustainability encompasses more than ecology; it includes the protection of human health and labor rights. The concentrated nature of REE production in specific geographic regions has raised concerns regarding resource governance.

In some regions, the lack of stringent regulatory oversight has led to occupational health hazards, including respiratory diseases caused by mineral dust and chemical exposure. Furthermore, the protection of indigenous lands and the assurance of fair labor practices are paramount. Ethical sourcing initiatives are increasingly focusing on traceability, ensuring that the minerals used in "green" products are not tainted by human rights abuses or local environmental neglect.

Transitioning to a Circular Economy

To mitigate the impact of primary extraction, the focus is shifting toward a circular economy model. Currently, the global recycling rate for REEs remains remarkably low—often estimated at less than 1%.

Urban mining—the reclamation of elements from end-of-life electronics—presents a significant opportunity. By developing sophisticated metallurgical techniques to recover neodymium from old hard drives or lanthanum from spent batteries, the pressure on virgin mining can be reduced. Additionally, researchers are exploring material substitution, looking for abundant alternatives that can provide similar performance without the environmental baggage of rare earths.

Policy Frameworks and Global Cooperation

The environmental challenges of REEs are global, requiring a coordinated international response. Policymakers are increasingly looking toward:

Harmonized Environmental Standards: Establishing a "floor" for environmental protections to prevent a "race to the bottom" in mining jurisdictions.

Digital Product Passports: Implementing tracking to verify the ecological footprint of minerals from the mine to the final consumer.

Regulatory Incentives: Providing support for companies that implement water-recycling systems and acid-recovery technologies in their processing plants.

Conclusion: Achieving a Symbiotic Future

The path to a sustainable future is paved with rare earth elements, but that path must be navigated with caution. The transition to green energy cannot be considered a success if it leaves a trail of environmental destruction. By prioritizing circularity, investing in cleaner refinement technologies, and enforcing rigorous ethical standards, the global community can balance the necessity of industrial advancement with the preservation of our planet’s ecological integrity.

About the Creator

Rahul Pal

Market research professional with expertise in analyzing trends, consumer behavior, and market dynamics. Skilled in delivering actionable insights to support strategic decision-making and drive business growth across diverse industries.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.