Living in the Frame: The Presented World and the Illusion of Choice

How curated realities shape our beliefs, behaviors, and sense of freedom

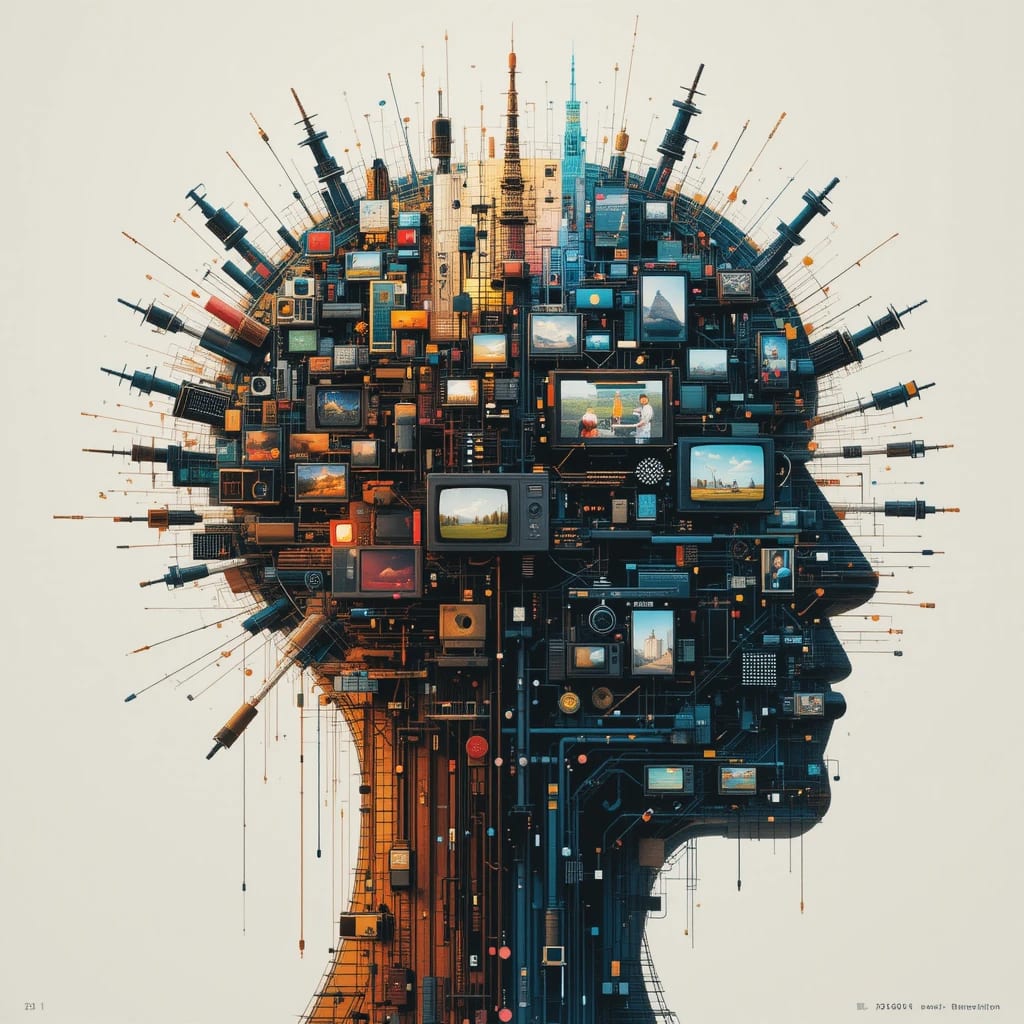

We often speak of freedom—freedom to choose, to think, to believe, and to act. Yet in the modern world, our choices are increasingly made within invisible boundaries. These boundaries are not enforced by governments or religions but by a more subtle force: the presented world. This world isn’t made of concrete or law. It’s made of narratives, images, data, and algorithms—a world curated for us, rather than chosen by us.

The presented world is the version of reality that is framed, filtered, and fed to us through the many mediums we interact with: television, news feeds, social platforms, search engines, advertising, and even education systems. It feels real. It looks like freedom. But it often functions as a mechanism of control, shaping not only what we see, but how we see.

The Illusion of Infinite Choice

On the surface, the modern world appears to offer endless options. From the thousands of streaming titles on Netflix to the millions of products on Amazon, it feels like we’ve never had more freedom. But this abundance is deceptive. What appears as infinite choice is actually a pre-filtered collection based on algorithms that study our behavior, predict our preferences, and then shape what we’re shown.

You may feel like you're choosing freely, but in truth, you're choosing from a carefully curated set of options designed to maximize engagement, profit, or influence. This is the first illusion of the presented world: the illusion of agency.

We are not seeing “everything” and choosing. We are seeing what has been chosen for us to see—and then deciding from within that narrowed field. Whether it’s the news you read, the clothes you buy, or the candidates you vote for, your field of view is framed long before you even begin to “choose.”

The Frame Is the Message

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan once said, “The medium is the message.” In the age of the presented world, we might add: the frame is the message. How something is presented—what is emphasized, what is cropped out, what tone is used—matters more than the content itself.

For example, the same protest can be presented as a righteous call for justice or a dangerous disruption of peace, depending on how it is framed by the media. A person’s statement can be empowering or offensive, depending on the snippet chosen and the surrounding commentary.

This framing doesn’t just change opinions—it constructs reality. Most of us cannot travel the world to verify events. We rely on presented versions. But when every piece of information is embedded in a context designed to steer interpretation, the presented world becomes a kind of simulation—convincing, emotionally charged, and often misleading.

Manufactured Consent in the Information Age

Noam Chomsky's concept of “manufactured consent” has never been more relevant. In the digital age, this manufacturing doesn’t require censorship—it requires saturation. The presented world is filled with so much information that important truths can be drowned out by irrelevant noise.

In such an environment, control isn't about hiding information. It’s about flooding us with so much content, so many interpretations, that truth becomes a matter of popularity rather than evidence. What trends becomes what’s seen. What’s seen becomes what’s believed.

Thus, public consensus can be steered not through coercion, but through carefully designed presentations. This is the second illusion: the illusion of consensus. We believe certain ideas are widely accepted not because they are, but because they dominate the presented space we inhabit.

The Emotional Economy

One of the most dangerous features of the presented world is its ability to bypass reason. Content is optimized not for depth or truth, but for emotional impact. Outrage, fear, envy, pride—these are the currencies of attention.

And attention is the economy of the modern internet. Every click, like, share, and scroll is data that feeds back into systems designed to hold you longer and influence you deeper.

In this emotional economy, rational debate is hard to sustain. Nuance doesn’t perform well in a feed that moves by the second. The presented world becomes a theater of extremes—where calm voices are drowned out and complex issues are flattened into slogans.

Escaping the Frame

So, how do we live ethically and intelligently in a presented world? The first step is awareness. We must understand that what we see is not all there is. The map is not the territory. The screen is not the world.

The second step is curiosity. Rather than reacting, ask questions. What is missing from this frame? Who benefits from this presentation? What perspectives are excluded?

The third step is deliberate exposure. Seek out voices that challenge your beliefs. Read beyond the headlines. Turn off auto-play. Step outside your digital bubble and engage with people, books, and experiences that don’t fit your usual profile.

Finally, we must learn to tolerate ambiguity. The presented world thrives on certainty and outrage because it’s easier to sell. But real understanding lives in grey areas. It is slow, uncomfortable, and often unsatisfying—but it is also deeply human.

The World Beyond the Frame

In the end, the presented world is not inherently evil. It is a tool—a powerful one. It can be used to inspire, inform, connect, and empower. But when left unexamined, it becomes a trap. A comfortable, familiar, convincing trap.

If we are to reclaim our minds and our freedom, we must step beyond the frame. We must learn to see not only what is shown to us, but what is not. Only then can we move from a life of reactive consumption to one of active, conscious living.

Because the world as it is—and the world as it is presented—are not the same. And only those who recognize the difference can hope to live with true clarity and freedom.

About the Creator

GoldenTone

GoldenTone is a creative vocal media platform where storytelling and vocal education come together. We explore the power of the human voice — from singing and speaking to expression and technique.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.