Life in Extreme Places

Microorganisms Living in Earth's Harshest Environments

Life in Extreme Places: Microorganisms Living in Earth's Harshest Environments

When we picture life on Earth, we often think of lush forests, deep blue oceans, or bustling cities. But beyond these familiar landscapes lies an astonishing truth: life has conquered even the most inhospitable corners of our planet. From boiling volcanic springs to the crushing depths of the ocean, microorganisms—tiny, often invisible forms of life—thrive where no other life dares to venture. Welcome to the world of extremophiles: Earth's ultimate survivors.

What Are Extremophiles?

Extremophiles are microorganisms (and sometimes other small life forms) that not only survive but actually require extreme conditions to live. They are divided into categories depending on the specific harsh environment they inhabit:

- Thermophiles love heat.

- Psychrophiles thrive in extreme cold.

- Halophiles flourish in salty environments.

- Acidophiles prefer acidic surroundings.

- Alkaliphiles enjoy high-pH, basic conditions.

- Barophiles (or Piezophiles) survive crushing pressures, like in deep-sea trenches.

Each of these organisms has evolved unique biochemical tools and adaptations that allow them to endure conditions lethal to most known life forms.

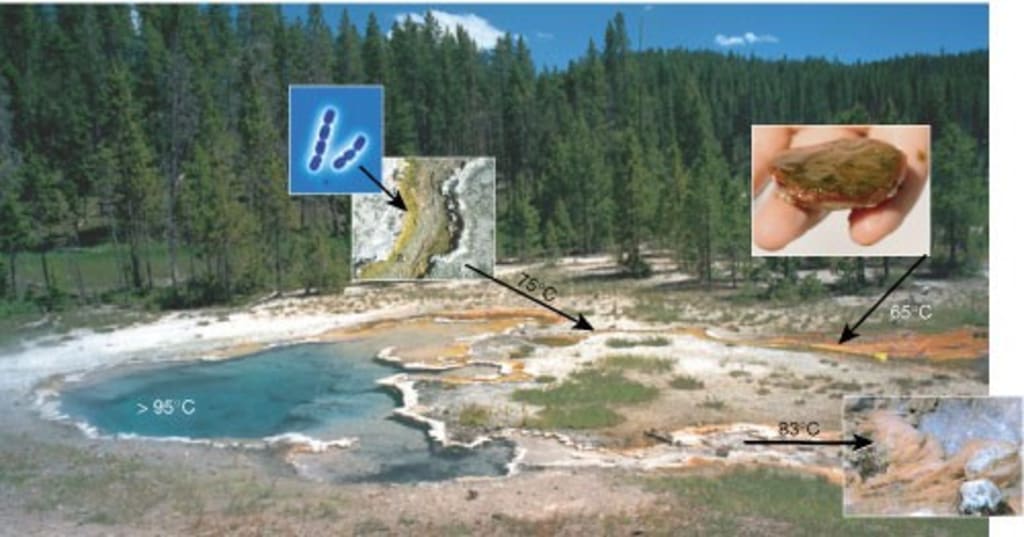

The Boiling Waters of Yellowstone

One of the first places where scientists recognized extremophiles was Yellowstone National Park. In the late 1960s, microbiologist Thomas Brock discovered heat-loving bacteria in the park’s scalding hot springs, where temperatures can soar above 80°C (176°F).

One particularly famous discovery was Thermus aquaticus, a bacterium that revolutionized modern biology. Scientists isolated an enzyme from it called Taq polymerase, which can withstand high temperatures without denaturing. This enzyme became essential to the development of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), a technique used in everything from forensic science to COVID-19 testing.

Without the humble extremophiles of Yellowstone, our modern genetic research landscape would look vastly different.

Life Beneath the Ice

While thermophiles bask in boiling heat, psychrophiles prefer things on the icy side. These organisms live in places like Antarctica's Lake Vostok, a body of water buried under nearly four kilometers of ice, isolated for millions of years.

In these frigid environments, psychrophiles produce special proteins that prevent ice crystals from forming inside their cells—a deadly event that would rupture and destroy most organisms. Instead, these microorganisms have flexible cell membranes and enzymes optimized for cold temperatures.

Their existence has astrobiologists buzzing: if life can thrive under Antarctic ice, could similar life forms exist on icy moons like Jupiter's Europa or Saturn's Enceladus?

Saltier Than the Sea

The Dead Sea’s name suggests a complete absence of life. Yet even there, in water ten times saltier than the ocean, halophiles—salt-loving microorganisms—carry on.

Halophiles have ingenious ways of surviving the dehydrating effects of salt. Some balance the external pressure by accumulating large amounts of potassium inside their cells, while others produce proteins specially adapted to function in high-salt environments.

Beyond their fascinating biology, halophiles have a pinkish pigment that often colors salty waters a vivid red or purple—a stunning reminder that even "dead" places can be teeming with unseen life.

Acid Baths and Alkaline Lagoons

Acidophiles and alkaliphiles push the boundaries of pH tolerance.

Acidophiles thrive in environments like acid mine drainage sites, where sulfuric acid can lower pH to near zero. One of the best-known examples, Ferroplasma acidarmanus, lives in toxic, acidic environments inside abandoned mines. These microorganisms have evolved highly impermeable cell membranes that keep acid from leaking into their interior, while also utilizing specialized proteins that continue to function at such hostile pH levels.

On the opposite end, alkaliphiles inhabit soda lakes and other high-pH environments, where the water is so basic that it can strip the oils off your skin. Instead of crumbling under the chemical assault, these organisms have adapted enzymes and cellular structures that remain stable and operational under alkaline conditions.

Crushing Pressures of the Deep

At the bottom of the Mariana Trench—Earth’s deepest oceanic abyss—the pressure exceeds 1,000 times that at sea level. Here, where sunlight never penetrates and temperatures hover near freezing, barophiles reign supreme.

Organisms like Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus have adapted flexible membranes and pressure-resistant proteins. These extremophiles are critical to deep-sea ecosystems, helping recycle nutrients and even playing a role in the breakdown of oil spills.

Deep-sea exploration missions continually uncover new species that astonish scientists, hinting that we’ve only scratched the surface of understanding life under extreme pressure.

How Do Extremophiles Survive?

The secret to the extremophiles' resilience lies in their molecular makeup. Many extremophiles possess:

Heat- or cold-stable enzymes: Specially adapted to maintain structure and function at extreme temperatures.

Protective molecules: Like antifreeze proteins, high-salt concentrations, or acid-neutralizing compounds.

Flexible or reinforced cell membranes: Depending on whether they face freezing or crushing conditions.

Efficient DNA repair mechanisms: Vital for surviving high-radiation environments, like those found near hydrothermal vents or high-altitude deserts.

Essentially, extremophiles have re-engineered the fundamental chemistry of life to fit their environments, a testament to evolution's limitless creativity.

Why Extremophiles Matter

At first glance, the study of extremophiles might seem like a scientific curiosity—a fun footnote about life at the fringes. But in reality, these tiny organisms have profound implications across multiple fields:

1. Astrobiology

If life can survive under Earth's most hostile conditions, then extraterrestrial life could very well exist in the extreme environments of other planets and moons. Missions to Mars, Europa, and beyond are guided by what we learn from Earth's extremophiles.

2. Medicine and Biotechnology

Enzymes from extremophiles have already revolutionized medicine and molecular biology. Besides PCR, extremophile-derived compounds are being investigated for novel antibiotics, cancer treatments, and industrial applications that require high heat or pressure.

3. Climate Change Studies

Understanding how microorganisms adapt to extreme conditions offers clues about how ecosystems might shift as Earth’s climate continues to change. Extremophiles could even help engineer solutions to environmental challenges, such as cleaning up toxic waste.

4. Philosophical Insight

Perhaps most profoundly, extremophiles expand our definition of what it means to be "habitable." Life is no longer confined to Goldilocks zones of perfect temperature and conditions. Life is inventive, stubborn, and adaptive beyond imagination.

The Future of Extremophile Research

We are only at the beginning of exploring extremophile life. Future missions will probe even more remote and hostile environments: the deepest parts of the oceans, the highest reaches of the atmosphere, and the underground oceans of distant moons.

With new technologies like autonomous submersibles, advanced genetic sequencing, and improved space exploration tools, we stand on the edge of extraordinary discoveries. Could extremophile-like organisms exist in the sulfuric acid clouds of Venus? Could Mars’ underground caves harbor hidden life?

The odds seem better every year, and each extremophile discovered on Earth adds another piece to this tantalizing puzzle.

Conclusion

Life, it turns out, is more flexible and daring than we ever imagined. From scalding geysers to frozen wastelands, from toxic sludge to crushing depths, extremophiles remind us that survival is often a matter of creativity and persistence.

In studying these extraordinary microorganisms, we don’t just learn about them—we learn about the boundless possibilities of life itself.

And perhaps, most thrillingly, we realize that Earth might not be the only place in the universe where life has found a way.

About the Creator

Jeno Treshan

Story writer Jeno Treshan creates captivating tales filled with adventure, emotion, and imagination. A true lover of words, Jeno weaves unforgettable stories that transport readers to far-off lands.

Comments (1)

I had no idea extremophiles were so diverse. Yellowstone's hot springs are a prime example. Who knew they'd lead to such important tech?