Ice Worms: The Glacier Ghosts Thriving Where Life Shouldn’t Exist

Glacier ice worms thrive where life should be impossible—feeding under the midnight sun and holding secrets that could reshape science.

Glaciers are often described as frozen deserts, beautiful but barren expanses of ice where survival is impossible. To early explorers trudging across the Alaskan wilderness in the 19th century, the idea of life hiding inside the ice was absurd. Snow was supposed to be sterile, a pure canvas untouched by biology. And yet, when the evening sun dipped behind the ridges, the surface of those glaciers came alive.

The snow rippled as if breathing. Tiny black threads wriggled upward in the twilight, carpeting the white crust in restless motion. These were not hallucinations born of fatigue but a discovery so strange that many scientists dismissed it outright. Worms in ice? Impossible. But the evidence kept returning from climbers, geologists, and naturalists until doubt was no longer sustainable. The glacier worm was real.

The Biological Paradox

Mesenchytraeus solifugus, as they would later be named, defy the fundamental rules of biology. Most creatures grow sluggish as temperatures fall, their metabolism slowing like a clock winding down. Ice worms reverse the equation. At 32°F they thrive, their cells firing with a burst of activity that scientists compare to a molecular furnace in overdrive.

The key lies in their mitochondria, the cellular power plants. In the ice worm, these organelles generate extraordinary levels of ATP, the chemical energy that fuels life. Instead of freezing to a halt, their physiology supercharges at the very threshold of cold.

This miraculous balance, however, teeters on a knife’s edge. Raise the temperature just a few degrees above freezing and catastrophe follows. Their tissues begin to disintegrate in a process called autolysis—self-digestion. Unlike polar bears or penguins, who endure cold through insulation and warmth, ice worms endure by binding themselves to the ice. Warmth is their predator.

A Nightlife on the Glacier

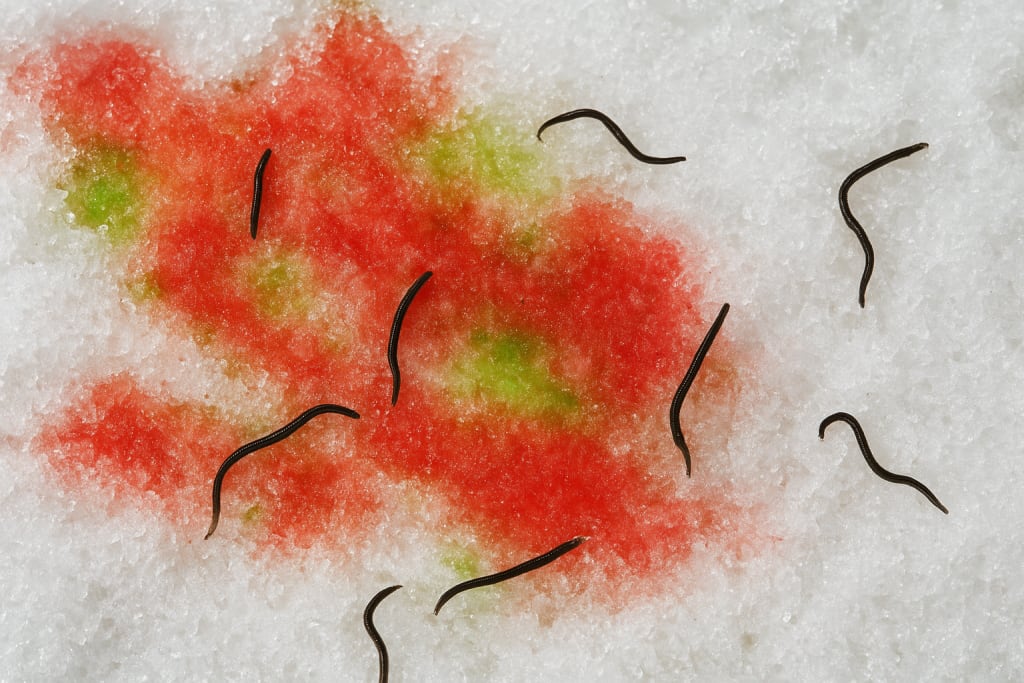

For all their fragility, ice worms are surprisingly active. As twilight falls, they emerge from thin films of water that thread between ice crystals. By the millions they slither across the glacier’s surface in search of food. Their diet seems impossibly meager: snow algae, pollen drifting on winds from forests hundreds of miles away, and microscopic microbes frozen in the ice.

The algae bloom in vibrant streaks of red and green, painting patches of “watermelon snow” that faintly smell of fruit. To hikers, it is a curiosity; to the ice worm, it is sustenance. Each night, these worms feast under the stars, leaving trails on the snow like faint brushstrokes, only to retreat again before daylight.

And they are not alone in this icy food chain. Birds such as the gray-crowned rosy finch swoop down to snatch them, carrying away not just a meal but also the worms’ genetic legacy. Scientists believe birds may have transported worms from glacier to glacier over millennia, scattering their populations across the coastal ranges of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington.

Billions Underfoot

To imagine their abundance is staggering. In some places, biologists estimate densities of billions of worms per square kilometer. Each step across a glacier after sunset may crush thousands unseen beneath the boots of climbers. The sheer biomass of these creatures challenges the assumption that glaciers are barren. Instead, they are pulsing ecosystems, powered by worms no larger than an eyelash.

By breaking down algae and organic debris, the worms enrich the meltwater that flows downhill. Streams gushing from glaciers carry not just ice but nutrients, feeding mosses, insects, and eventually the forests below. In this way, the glacier worm acts as a hidden engineer of alpine life, bridging frozen heights with fertile valleys.

Relics of an Ice Age

The mystery of their distribution stretches back thousands of years. Genetic studies suggest that during the last Ice Age, worms ranged widely across vast frozen corridors. As the glaciers retreated, their descendants became marooned on isolated ice fields. Today, distinct northern and southern lineages survive, separated by hundreds of miles yet still carrying traces of their shared ancestry.

Some scientists even suspect that long-distance dispersal continues. A bird feeding on worms in Alaska may later drop a living stowaway on a glacier in Washington, explaining odd pockets of genetic overlap. If true, it means that the fate of the glacier worm has always been tied not only to ice but also to wings.

A Medical Frontier Hidden in Ice

Beyond their ecological intrigue, ice worms may illuminate mysteries of human health. Their ability to supercharge mitochondria at freezing temperatures could hold medical value. Researchers have speculated that studying these mechanisms might reveal new strategies to combat diseases rooted in mitochondrial dysfunction—conditions where human cells fail to generate energy properly.

What allows a worm to thrive where life should falter could one day help us extend the limits of our own biology. Like deep-sea extremophiles that inspired new drugs and enzymes, glacier worms may hold biotechnological secrets hidden in their icy DNA.

A Race Against Melting Time

But there is a darker chapter to this story. Glaciers are shrinking at unprecedented rates across the Pacific Northwest. Ice that once sprawled for miles has receded into thin ridges and fractured tongues. With each summer of accelerated melting, the habitat of the ice worm collapses. Unlike mountain goats or alpine flowers, they cannot climb higher or adapt to warmer air. When the glacier goes, they go.

The loss would not be just ecological but symbolic. Ice worms remind us that life finds a way even in the harshest conditions, bending the rules of existence itself. To watch them vanish would be to watch a paradox dissolve, a whisper of resilience erased by heat.

The Ghosts of the Glacier

On a cool summer night, as the last light fades from the sky, one can kneel on the surface of a glacier and see them emerge—slender, dark, restless. To some climbers they seemed like spirits of the mountain, tiny phantoms rising from the ice. To scientists they are enigmas, their very existence a contradiction.

In their fragile wriggle lies both wonder and warning. The worms show that nature’s creativity has no limits, that ecosystems bloom in places we once thought empty. But they also show how quickly a miracle can vanish. As the ice retreats, so too does a living paradox, leaving behind only the silence of melting snow.

References

1. Main, D. (2021) Meet the ice worm, which lives in glaciers—a scientific 'paradox'. National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/amazing-ice-worms-threatened-melting-glaciers (Accessed: 28 August 2025).

2. Hotaling, S. et al. (2019) ‘Long-distance dispersal, ice sheet dynamics and mountaintop isolation underlie the genetic structure of glacier ice worms’, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 286(1905), 20190983. Available at: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2019.0983 (Accessed: 28 August 2025).

3. Nichols College North Cascade Glacier Climate Project (n.d.) Ice Worms. Available at: https://glaciers.nichols.edu/iceworm/ (Accessed: 28 August 2025).

About the Creator

Jiri Solc

I’m a graduate of two faculties at the same university, husband to one woman, and father of two sons. I live a quiet life now, in contrast to a once thrilling past. I wrestle with my thoughts and inner demons. I’m bored—so I write.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.