Finding a Way Through Swampy Ground to Cross the Bering Bridge

Animals and humans must have had a strong desire to reach the Americas.

Contrary to popular belief, the land bridge that spans the Bering Strait and endures for a large portion of the last Ice Age was probably quite different. According to a new study, the area between Asia and North America comprised boggy wetlands dotted by rivers and higher ground rather than a mixture of grassland, tundra, and ice sheet. The question of how and when the earliest humans arrived in the Americas is further complicated by the results.

Paleontologists have long been perplexed by the abrupt emergence of land-dwelling Asian species in North America, and occasionally the opposite. It was eventually discovered that the sea levels were so much lower during the previous Ice Age that it was feasible to cross the present-day Bering Strait on dry land, forming the vast area known as Beringia.

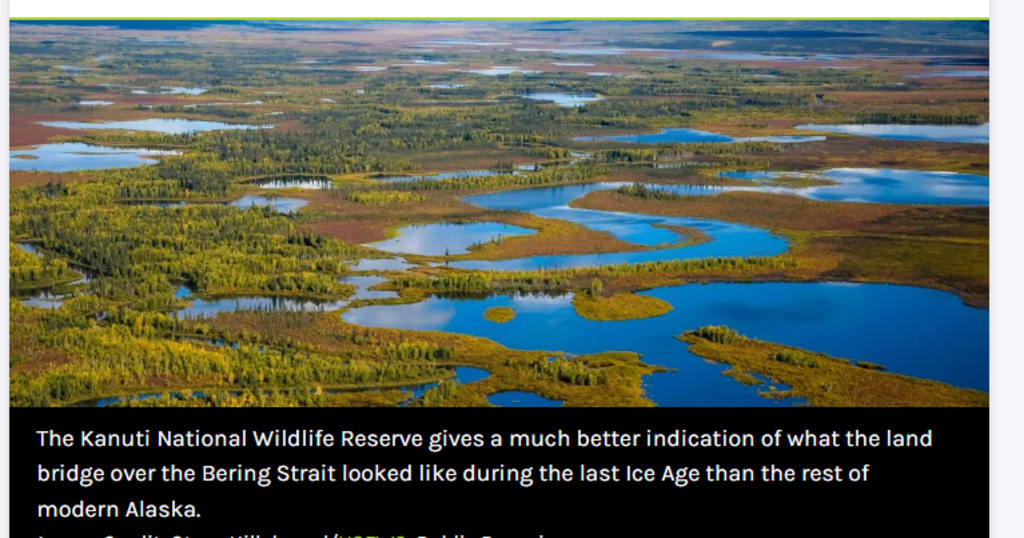

The terrain was presumed to be dry, at the very least. Although the entire region was obviously considerably colder 36,000–11,000 years ago when the two were united, the majority of Alaska and the eastern tip of Siberia are so similar that it was supposed the land in between was identical to both. But that changed after the first set of sediments of the proper age were found on the bottom where the bridge used to be.

In a statement, Professor Sarah Fowell of the University of Alaska Fairbanks stated, "We were searching for a number of sizable lakes." "In reality, we discovered evidence of numerous small lakes and river channels."

The discovery is not that shocking in retrospect. Because the land bridge is significantly lower than the terrain on either side and has been submerged by increasing waves, it is now under the ocean—not because it has subsided. Rivers could have flowed off both continents to gather there because of the lower altitude, at least during the summer. A marshy riverine environment could result from those rivers feeding the expected lakes due to uneven topography, yet flat ground allows the water to spread extensively. Fowell and his associates didn't even need to look indicating that one in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta is too far away for contemporary parallels.

Dr. Jenna Hill of the U.S. Geological Survey stated, "We have been searching on land to try to reconstruct what is underwater." "But that doesn't tell you what was on land between Siberia and Alaska that is now submerged."

Fowell, Hill, and associates focused on 36 locations that were previously identified as lower-lying locations and employed the R/V Sikuliaq to gather core samples from the sea bottom in regions that had been above sea level at the pertinent time. They believed these to be the lakes of the time. The surrounding environment at each site is depicted by pollen, DNA, and intact objects like egg cases and leaves. These show that while some trees, perhaps on higher ground, thrived, a large portion of the area was aquatic, drawing wading birds.

Although the work is not yet published, it is so important that it serves as the foundation for seven papers at the American Geophysical Union Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., this week.

The study of past ecosystems is the responsibility of paleogeologists everywhere, but understanding how some species crossed the Beringia and why others did not is of far greater interest.

Short distances of marsh could be traversed by humans and other creatures like bison and mammoths, but hundreds of kilometers were likely a different story. As a result, the crew is certain that improved travel chances were offered by higher ground.

"We are still seeing evidence of mammoths, even though it may have been marshy," Fowell stated. At one location, mammoth DNA was even found. "Grazers were present even though the area was primarily made up of ponds and floodplains; they just moved uphill after higher, drier areas."

However, it is simpler to understand why American camels and woolly rhinoceros, among others, never made the entire journey because they had to pick their route from one dry outpost to another, occasionally pushing through overlapping swamps. According to Hill, "the wet, watery landscape could have been a pathway for species that travel by water or a barrier for some species." "This fits into the larger picture in that way." It has been suggested that there is a "Beringian Gap" because of the fact that anything stopped these animals from finding their route.

One of the most contentious scientific issues of the last few decades has been the arrival of humans in the Americas. The majority of northern North America was covered in ice at the time the Bering Bridge was built, which meant there was nothing to eat. It was long believed that the first individuals to cross the bridge traveled south through a tunnel free of ice around 14,000 years ago.

Since then, there has been intense discussion on how the first Americans came to the Americas due to mounting evidence suggesting there were people there long before the corridor opened. There have been proposals for "sea ice highways," coastal routes, and even more straightforward ocean crossings. This could alter how the remainder is perceived if the ability to traverse brief watery sections was a necessary prerequisite for the first portion of the trip.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.