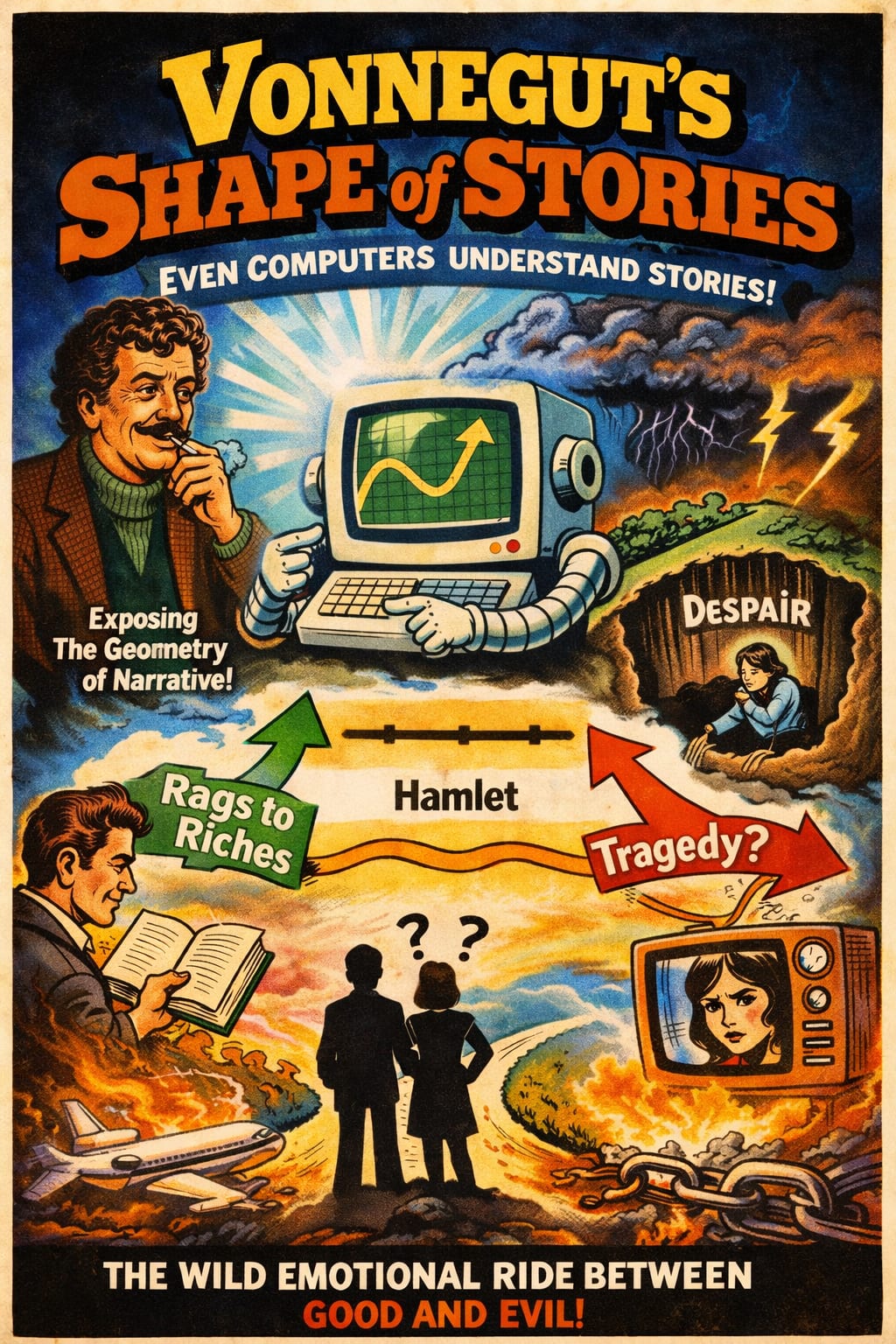

Vonnegut's Shape of Stories

Why Even Computers Understand Stories

Vonnegut's Shape of Stories: Why Even Computers Understand Stories

Peter Ayolov, Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski", 2026

Abstract

This article theorises 'the new paradigm of mass communication ' and ‘the media scenario ' and examines Kurt Vonnegut’s concept of the ‘shapes of stories’ as a key to understanding the new paradigm of mass communication and the logic of the media scenario. Revisiting Vonnegut’s early and long-dismissed insight that narratives can be mapped as simple movements between good and bad over time, the article situates his graphical models within contemporary media environments dominated by platforms, algorithms, and participatory storytelling. Drawing on Vonnegut’s diagrams and their later empirical confirmation through computational literary studies, the article argues that narrative simplicity is not a reduction of meaning but a structural condition of emotional orientation. In digital culture, these basic narrative arcs migrate from literature into journalism, politics, and platform media, where they function less as representations of reality and more as behavioural templates that organise attention, expectation, and collective emotion. The article further proposes that media scenarios increasingly impose pre-structured emotional curves onto public life, transforming events into recognisable plots and citizens into participants within scripted arcs of crisis, recovery, decline, or ambiguity. Vonnegut’s insistence on the straight line—exemplified by his reading of Hamlet as an emotionally flat narrative—is interpreted as a critical counterpoint to contemporary dramatisation: a reminder that life itself resists narrative closure. By linking narrative form, emotional rhythm, and media power, the article reframes Vonnegut’s playful diagrams as a serious theoretical tool for analysing how stories shape not only meaning, but social time, moral judgement, and the experience of reality in the age of mass communication.

Keywords

Kurt Vonnegut; shapes of stories; emotional arcs; narrative structure; media scenario; new paradigm of mass communication; storytelling and algorithms; dramatisation; attention economy; narrative simplicity; Hamlet; computational literary analysis; emotional valence; public discourse

The Shapes of Stories

“Stories have very simple forms, forms that even computers can understand.”

-Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut’s rejected master’s thesis from 1947, titled The Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tasks, occupies a peculiar place in the history of literary theory. It was dismissed as ‘too simple’ and ‘too playful’, despite advancing a bold hypothesis: all stories possess a structure that can be represented graphically, and movement between good and evil functions as a primary organising principle of narrative. Vonnegut insisted that simplicity was not trivialisation but a method for revealing universal patterns. In 1971 the University of Chicago finally accepted the novel Cat’s Cradle as the equivalent of the rejected thesis and awarded him the degree that had previously been denied. This historical context illuminates the later development of Vonnegut’s idea of the ‘shapes of stories’. His proposal to place time on a horizontal axis and evaluative fortune on a vertical one is not merely a pedagogical gesture but a continuation of his original concept of structural fluctuation. The graphic representation of movement between rise, fall and indeterminacy seeks to capture the basic trajectories through which narrative produces effect. The diagrams—‘Man in a Hole’, ‘Boy Meets Girl’, ‘Cinderella’, ‘From Bad to Worse’, and ‘Hamlet’—function as analytical abstractions that make it possible to identify recurring rhythms of change. ‘Man in a Hole’ models crisis and recovery; ‘Boy Meets Girl’ traces the reversals of desire and loss; ‘Cinderella’ presents a triadic structure of compensation; continuous decline articulates existential degradation; and ‘Hamlet’ demonstrates how a narrative can refuse stable evaluation. The last form is especially central to Vonnegut’s philosophy: life often does not allow one to determine whether an event is a blessing or a curse, and it is precisely this ambiguity that produces a sense of truthfulness. In recent decades, computer-assisted literary analysis has confirmed his intuition. Algorithms for analysing emotional valence process thousands of novels and reveal a limited repertoire of recurring ‘emotional trajectories’. The detected models—‘rags to riches’, ‘riches to rags’, ‘Icarus’, ‘Oedipus’, ‘Cinderella’, ‘Man in a Hole’—correspond directly to Vonnegut’s graphic forms. Although the method neglects context and style, it demonstrates that stories organise themselves around a small number of structural movements, endlessly repeated in new variations. It is in this context that Vonnegut’s famous joke, delivered in public lectures, acquires its full meaning: that stories have forms so simple that ‘even computers can understand them’. This is neither a mockery of literature nor of algorithms, but a comment on the nature of narrative itself. It suggests that storytelling always tends towards reduction—towards a simplified movement from birth to death, from good to bad and back again.

Algorithms succeed in processing vast textual corpora precisely because stories repeat a limited number of patterns. Machines understand stories because stories are already structured like algorithms: sequences of fluctuations revolving around fundamental categories such as hope, loss, decline and recovery. Vonnegut deploys the joke as a philosophical diagnosis: human storytelling necessarily simplifies the world, translating complex moral and existential processes into traceable lines of change. This does not mean that form exhausts content. The graph is a reduction designed to capture rhythm rather than meaning. A rise may signify political liberation or personal romance; a fall may indicate tragic guilt or social injustice. Form registers movement without determining moral value or cultural significance. This is precisely why it is useful: it allows structural decisions in narrative to be identified without replacing its multilayered semiotic and ethical dimensions. The method of drawing narrative arcs also serves a practical function. It exposes stagnation, excessive acceleration, missing motivating events and unearned reversals. It reveals structural inconsistencies that remain invisible to purely intuitive reading. Yet there is also a risk: excessive reliance on form can turn narrative into schema. Vonnegut himself warns against this by showing how Hamlet escapes every attempt at categorisation and sustains a space of indeterminacy in which meaning remains mobile and evaluation unstable. Ultimately, Vonnegut’s proposed simplicity is not a primitive reduction but a methodological stance. It assumes that stories can be understood by examining their movements: from point A to point B, from good to bad, from fall to rise. The simple line sharpens attention to structure without cancelling complexity. For this reason, his early text—dismissed as ‘too playful’—proves to be a foundational contribution to the philosophy of narrative: structures that appear elementary are in fact the key to understanding how stories move, how they affect, and why they remain recognisable even to machines.

The Emotional Arc of Narrative

“The emotional arcs of a large body of stories reveal a set of basic forms common across cultures and eras.”

— Andrew J. Reagan

The article ‘The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes’ (2016) by Andrew J. Reagan and his co-authors lays the foundation for one of the most influential findings in the study of narrative through big data: stories, regardless of genre or historical period, follow a limited set of stable emotional arcs. These arcs describe changes in emotional valence—the movement between good and bad, rise and fall—within a narrative. The study explicitly revisits Kurt Vonnegut’s once-dismissed hypothesis about the shapes of stories and seeks to validate it empirically by applying computational methods and algorithms to the analysis of large textual corpora. The discovery becomes possible through the development of digital libraries, natural language processing, and analytical tools that allow literature to be treated as a data set. Each text is analysed as a time series over which a sliding window of tens of thousands of words moves. At each position, the average ‘emotional value’ of the words is calculated using a specialised sentiment lexicon, producing a curve—an emotional arc. This reduction does not capture irony, subtext, or semantic ambivalence at the level of individual phrases, but across sufficiently large segments it extracts a stable signal of overall emotional dynamics. It is precisely this stability that allows texts to be grouped according to structural similarities in their emotional curves. The analytical techniques employed—singular value decomposition, hierarchical clustering, and self-organising maps—independently reproduce the same result: stories in the English-language canon cluster around six basic forms. The first is the classic rise, in which the plot begins at a neutral or low level and steadily ascends, structuring a ‘rags to riches’ trajectory. The second is its inverse, a continuous decline organising the tragic movement ‘from riches to rags’. The third form, ‘man in a hole’, depicts a fall followed by recovery, a cyclical arc deeply embedded in Western storytelling traditions. The fourth, ‘Icarus’, rises sharply before collapsing abruptly. The fifth, ‘Cinderella’, traces a rise, a fall, and a renewed ascent. The sixth, ‘Oedipus’, begins with a fall, moves through a brief recovery, and ends in definitive collapse. The significance of these forms becomes clearer through control tests. When the same methods are applied to texts with randomly shuffled words or to algorithmically generated noise, no structure appears. The emotional profile is flat, lacking distinctive turns or clusters. The absence of curves in these null models demonstrates that real stories possess an internal emotional geometry that cannot be reduced to chance. This geometry is also linked to popularity. Stories structured around the Icarus, Oedipus, or double ‘man in a hole’ arcs circulate and are shared more intensively, while simple forms of continuous rise or continuous fall show weaker social virality.

The reason lies in human expectations: dramatic contrast, anticipatory tension, and bidirectional change generate stronger emotional charge. Stories unfold through a series of reversals that capture attention because they resonate with internal psychological rhythms. This reveals a deeper connection between emotional arcs and patterns of human behaviour. Social processes—romantic relationships, political crises, economic cycles, ideological ascents and collapses—often follow the same structural gestures as fiction. Network theory, behavioural economics, and the analysis of social dynamics show that mass behaviour is governed by rhythms of hope, decline, recovery, and renewed tension. Narrative forms thus emerge as forms of collective experience. Storytelling, in this sense, functions as a mechanism for modelling social emotionality. When media, television series, political campaigns, and digital platforms repeatedly reproduce the same dramaturgical patterns—crisis, escalation, climax, catharsis—audiences do not merely observe them but begin to experience the world through them. Narrative structure becomes a behavioural template. It prescribes what a crisis should look like, where the turning point lies, and when catharsis must occur. People step into the roles these forms make available. Narrative structure thus becomes an instrument for managing attention and emotion. When sufficiently large groups undergo the same emotional movements, a collective rhythm emerges, capable of accelerating panics, amplifying enthusiasm, catalysing conflict, or producing moral mobilisation. In this sense, the forms are not only descriptive but prescriptive: they construct expectations that reality itself begins to follow. The question, therefore, is not whether people tell stories in the same ways, but why these ways exert such power. Emotional arcs describe the minimal structures of human feeling, but also the forms through which societies understand themselves. Awareness of these arcs is not merely a technical skill but an ethical task: to use them not for manipulation, but to create spaces of understanding, to expand possibilities, and to free the human role from pre-written scripts. The study ultimately confirms Vonnegut’s joke that stories have such simple and recognisable forms that even computers can understand them. Why, then, humans forget the simplicity of their own narratives and complicate them into paradox remains an open question—perhaps this tension between the simple and the complex is itself part of the story of life.

Fictional Humans and Human Fictions

“We are what we pretend to be, so we have to be very careful what we choose to pretend to be.”

— Kurt Vonnegut

The essay ‘Fictional Humans and Humanist Fictions’ foregrounds the question of how literature creates people, while humanity creates fictions. This double movement lies at the core of Timequake (1997), Kurt Vonnegut’s semi-autobiographical novel, which turns the boundary between metaphor and reality into a field of inquiry. At the centre of the text stands the idea that humans live simultaneously in a biological world and in invented structures through which they define, recognise and sometimes lose themselves. One of the key conceptual axes is the temporal ‘quake’ that forces humanity to relive ten years without the possibility of choice. This enforced repetition exposes the hidden mechanics of human behaviour. When will disappears, only habit remains: action becomes a function of the past, and life reveals itself as an automated rehearsal. Fiction thus uncovers the structural fragility of the ‘human’, showing how easily it can be replaced by the mechanical. A second layer of the analysis concerns the disintegration of narrative form itself. The text is composed of scattered fragments, notes, anecdotes, aphorisms, paradoxes and autobiographical detours. This is not a weakness but a principle: fragmentation mirrors the dispersed consciousness of modernity. The world is no longer coherent, and language should not pretend to be whole. The novel’s structure demonstrates that fiction is not a smooth surface but a space of cracks through which reflection can enter. The fictional human is not a completed character but a constructed form assembled from imperfections. The theme of repetition acquires a social dimension as well. The novel depicts a culture that operates through cycles—advertising, elections, scandals, mass hysterias. The constant circulation of the same content turns people into carriers of roles that repetition has rendered inevitable. In this sense, the fiction of society overtakes the fiction of literature. Human life begins to resemble a script written by external forces: the market, the media, ideology, technology. The illusion of choice conceals the fact that patterns of behaviour are already structured in advance. When the temporal ‘quake’ ends and free will returns, people fall into chaos. They no longer know how to act without the predetermined track of repetition. Freedom, stripped of habit, proves paralysing. This crisis reveals a paradox: humans claim to desire freedom, yet almost always move according to fictions they have reproduced themselves or that have been imposed from outside. Life in repetition is a form of servitude, but freedom without a narrative stands on the edge of disintegration. From this tension arises the fundamental question: what does it mean to be human? The text suggests that humans are beings who create stories not to embellish reality, but to make it inhabitable. Fictional forms are not deceptions but instruments of orientation. Myths, novels, comedies and tragedies all function as structures through which moral imagination is shaped. Human fictions sustain the possibility of action. Without them, life collapses into repetition without direction.

Yet fiction has another side: it can become an ideological mechanism. Social regimes also generate narratives—of progress, prosperity, identity—that organise behaviour. Here the boundary between the fictional and the political dissolves. People become characters in stories they did not write themselves, and fiction shifts from a liberating force to an instrument of governance. Timequake implies that the only way out lies in an ethics of compassion. Fiction can be salvific if it is used not for control, but for understanding. It must reveal complexity, expose error, and open space for choice. The fictional humans in the text function as mirrors: they render visible human weakness, fear and hope. Through them, the reader recognises personal vulnerability, and this recognition generates a new form of community. Literary fiction thus becomes a critique of the humanist fictions society uses to stabilise itself. It dismantles the myths of autonomous individuality, continuous progress and rational order, replacing them with a more fragile but more human perspective: humans are not masters of fate, but they are capable of producing meaning through shared experience. Ultimately, the novel insists that the living human is always more than the role being played. Fictional humans are a means of exploring the limits of human fictions, but the deeper aim is to arrive at a renewed understanding of humanity itself. The text affirms that imagination remains the last territory of freedom—not because it invents new worlds, but because it allows the rethinking of the one in which people live. The purpose of humanity, of culture, of fiction, of literature and of civilisation as a whole converges in a single task: to produce new, authentic humans. Even when existence unfolds within fictional worlds, metaphysical constructions or emerging metaverses, the task remains unchanged—to create persons capable of being truthful within the inevitable fictions that constitute human life.

The Straight Line of Life

‘The truth is that we know so little about life that we do not really know what is good news and what is bad news. Life happens while you are busy making other plans.’

— Kurt Vonnegut

In his well-known lecture on the shapes of stories, Kurt Vonnegut draws the emotional trajectory of Hamlet as a horizontal straight line. In this diagram there are no rises, no falls, no catharsis, no victory or defeat in a moral sense—only a steady movement from beginning to end. The irony is that this is precisely the line Vonnegut defines as ‘the most truthful story ever told’. It presents life as it is experienced by most people: without dramatic turns, without stable interpretations, without clear labels of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Hamlet’s life is not organised into dramatic arcs; every event remains indeterminate. His father’s death is a tragedy, yet the ghost that explains it may be either a sign of justice or a deception. The killing of Polonius is horrific, but its consequences are ambiguous. The final duel can be read as liberation or as punishment. Shakespeare’s tragedy refuses to turn existence into a plot; Vonnegut merely visualises this refusal. The straight line thus becomes an image of the existential vacuum—of that flat, almost invisible flow of time that modern humans desperately try to replace with forms, drama, and stories. From an early age people are trained to expect their biographies to arrange themselves as narratives, complete with obstacles, reversals, awakenings, and moral lessons. Hamlet exposes this illusion by presenting an existence that does not follow dramaturgical logic. The idea of ‘development’ is a product of desire, not a reflection of reality. Real life, as Vonnegut’s line suggests, is continuity rather than plot. The straight line does not mean an absence of action, but an absence of extractable meaning from action. Hamlet constantly attempts to interpret events, to locate a moral axis, to find a point of orientation, yet every interpretation collapses. Every decision generates deeper uncertainty. This is the drama of human existence: not the lack of events, but the lack of a clear emotional geometry. Hamlet becomes an enlarged caricature of the contemporary subject—someone who feels that ‘nothing is happening’, or that whatever is happening cannot be arranged into a meaningful order. From this follows the power of the straight line: it reveals a psychological dependence on narrative. People cannot endure the flatness of everyday life, so they instinctively translate the even surface of time into arcs of destiny.

Religion is a narrative: creation, fall, redemption. History is a narrative: crises, rises, revolutions. News imitates dramatic structures: disaster–recovery, scandal–reform. Science is presented through the hero’s journey: problem–breakthrough–salvation. All these forms soften the anxiety produced by the possibility that life has no plot. Yet the straight line remains the most accurate diagram of daily existence. The overwhelming majority of time unfolds through repetition: waking, work, screens, food, fatigue. This monotony is difficult to accept, so imagination bends it into curves. Love is framed as an odyssey, career as ascent, politics as battle. The social world rewards such autofictions; every social media profile is a miniature drama of peaks and collapses. In reality, life continues along a straight line, while dramaturgy remains its narrative overlay. This is why Vonnegut’s line becomes threatening: it reveals that the story industries—media, politics, advertising, entertainment—function by refusing to accept the flatness of life. The economy of attention feeds on arcs, not planes. Without drama, markets falter; without narrative, politics loses force. Yet beneath all the turns, people continue to live along straight lines. Vonnegut sees here not tragedy but paradox: humans construct plots in order to escape the truth that life may be without plot. Hamlet fails to find meaning because he expects meaning to be discovered rather than produced. His line reminds us that meaning is the result of storytelling. When the story ends, only the movement of time remains. The straight line is the primary form of life; all other arcs are its ornaments. Perhaps the most honest response is not to bend it further, but to acknowledge its nakedness—to accept that life is not necessarily a story, but a sequence of scenes experienced by a single consciousness. From that nakedness begins the freedom to invent one’s own form.

The Curved Line of Drama

“Life is not a story. You go through things and you don’t understand what they mean. It’s only later that you find out what they were about. People want to believe that life has a structure. But it doesn’t. We give it a structure so that we can endure it. Any attempt to tell the truth is a kind of failure, because the truth is bigger than anything we can write. Stories are a way of avoiding the truth.”

— Charlie Kaufman, BAFTA Screenwriters’ Lecture, 2011

In his lecture ‘The Shapes of Stories’, Kurt Vonnegut discovers that narratives can be mapped as emotional trajectories over time, revealing that what people call meaning is often nothing more than a curve imposed on experience to make suffering, luck, and coincidence bearable. Vonnegut discovers in Shakespearean tragedy not so much a plot as a diagram of human existence – flat, indeterminate, stripped of clear rises and falls. The straight line becomes a visualisation of an existential truth: people expect fate to have a shape, but more often it does not. It is precisely this idea that underpins the famous scene ‘And why the fuck are you wasting my two precious hours with your movie!?’ from the film Adaptation (2002), one of the most original metatexts about what it means to write a story and what it means to search for meaning. In the film, the characters merely resemble the director and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and Robert McKee, one of the most influential screenwriting gurus. They are not documentary portraits but fictional doubles, created to stage an indirect debate about the essence of screenwriting craft. This is a clash between two worldviews: that of the straight line – life as stasis, hesitation, an ongoing ‘nothing much happens’ – and that of drama, which insists that without events there is no story, and without story there is no human being.

‘Charlie Kaufman’: ‘What if a writer is trying to create a story in which not much happens? Where people don’t change, don’t have any revelations. They struggle, they’re frustrated, and nothing gets resolved. More like the real world.’

‘Robert McKee’: ‘The real world? The real fucking world. First of all, if you write a script without conflict or crisis, you’ll bore the audience to tears. Second — nothing happens in the world? Are you out of your mind? People are murdered every day. There’s genocide, wars, corruption. Every fucking day somewhere in the world someone sacrifices their life to save another. Every fucking day someone somewhere makes a conscious decision to destroy another human being. People find love. People lose it. A child watches his mother beaten to death on the steps of a church. Someone starves. Someone betrays their best friend over a woman. If you can’t find these things in life, then, my friend, you know nothing about life. And why the hell are you wasting my two precious hours with your movie? I get nothing out of it. Not one fucking thing.’

‘Charlie Kaufman’: ‘Okay… thank you.’

The scene begins with the insecure screenwriter posing a question that sounds like an echo of Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’. ‘What if someone wants to tell a story in which nothing happens?’ he asks. ‘Where people don’t change, don’t have revelations, remain disappointed — like in real life?’ This is a plea for the legitimisation of the straight line. A desire to justify existence without an arc. A creative version of existential paralysis. The seminar guru – a character inspired by McKee but transformed into a fictional caricature – responds with an outburst that shatters the idea of equivalence between ‘existence without plot’ and truth. His cry ‘The real fucking world?’ calls into question the very notion of a ‘reality without events’. The entire tirade is constructed as a catalogue of dramatic possibilities that reality offers every single day. The world is too intense to be reduced to a flat line. At this moment, the film stages a collision between two philosophies: one sees life as a flat field of hesitation, the other as a chaotic but unavoidable sequence of confrontations. Adaptation complicates this conflict by introducing the double Donald – Charlie’s brother, who effortlessly embraces all the rules that Charlie rejects. Donald accepts the formula, sells a script, achieves success. He embodies the dramatic curve; Charlie embodies the straight line. And yet the narrative demonstrates that the two cannot exist in complete separation. When Charlie finally begins to write, his life itself starts to resemble a film – pursuit, accident, death, despair. Adaptation thus visualises the paradox: every attempt to flee from drama inevitably generates its own dramatic contour. Narrative here appears not so much as artistic fabrication but as a form of survival: a way of imposing structure on chaos, of marking significance where the plane of time appears mercilessly smooth. At this point, a deeper metacommentary emerges. The media scenario and popular culture, in their attempt to ‘domesticate’ drama, produce script models that replace reality with structure. Audiences begin to live according to the arcs they expect to receive. Conflict becomes a necessity, catharsis a mandatory step, meaning a product that must be ‘delivered’. Drama becomes the norm, and flatness becomes unthinkable. And when someone asks about a story without events, the answer is the guru’s scream – not because it must be so, but because this is how we have learned to see the world. In the end, the scene from Adaptation returns us to the same place where Hamlet began: the human being oscillates between the straight line of life and the dramatic curves the mind draws in order to escape its emptiness. The truth likely lies between them – in the effort to acknowledge the flatness, while still finding within it a form that brings one closer to oneself.

The Cyberdrama of the Bookish Human

“The computer is the most powerful representational medium ever created, and it should be entrusted to the hands of storytellers.”

— Janet H. Murray

Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace (1997) is a book by Janet H. Murray that explores how digital technologies transform storytelling. Murray analyses hypertext literature, interactive cinema, early chatbots and video games in order to show how digital environments generate new forms of plot, participation and narrative structure. She formulates four core properties of the digital medium — procedurality, participation, spatiality and encyclopaedic scope — and explains how these reshape the future of narrative. As early as 1997, Murray anticipates the emergence of new media genres, including MUD (Multi-User Dungeon) worlds, 3D interactivity, virtual drama and intelligent agents. The book was expanded in 2016, so that its very existence in two versions marks a transition between two centuries and even between two ways of thinking about media. The 2016 addition no longer speaks of ‘the future of narrative’ as a hypothesis, but describes it as a partially realised reality.

In the text, Hamlet functions as a metaphor for the supreme capacity of narrative to express the inner life of the human being, while the question ‘Hamlet on the Holodeck?’ asks whether future cyberdramas can capture the same truth about the human condition that Shakespeare renders through Hamlet’s soliloquies. But what is the ‘holodeck’? The holodeck is a fictional technology from Star Trek: The Next Generation, representing a fully immersive virtual environment — a room in which the computer generates simulations of places, people and events that can be experienced as reality. The user can enter, interact freely and participate in a narrative that responds to their choices. For Murray, the holodeck is a metaphor for the future of storytelling — a space in which the reader or player becomes an acting subject and the story unfolds in response to their actions. She calls it an ‘optimistic technology for exploring the inner life’, because it enables both external interaction and deep psychological engagement.

The book traces how early games such as Zork and experiments with hypertext point towards future forms of cyberdrama — interactive fictional universes that combine dramaturgy, simulation and choice. Murray argues that the digital medium will not destroy literature, but will extend its possibilities, just as cinema once extended the novel. The central message of the book is that there is no reason to fear change: virtual media, like the book and cinema before them, will become new forms of human imagination, provided that they are approached with critical awareness, ethics and creative responsibility. The birth of a new medium always carries a dual sensation — excitement and fear. Every technology that expands human capacities simultaneously unsettles them and threatens established understandings of what it means to be human. The boat, the automobile, the aeroplane — all are magical extensions of arms and legs; the telephone extends the voice; the book extends memory. The computer of the 1990s unites all these extensions, becoming a machine for travel, for communication across oceans, for storing and retrieving information — and at the same time controlling fighter jets and defeating chess grandmasters. It is hardly surprising that some perceive it as a playful omnipotent spirit, while others see it as Frankenstein’s monster.

For Janet Murray, however, the computer gradually comes to resemble not an enemy, but the film camera of the 1890s or the video camera of the 1980s — a revolutionary medium that humanity is only beginning to learn how to use as a storyteller. The computer can be more than a calculating instrument. At the heart of the machine there may lie creativity. What do computer science and literature share? Imagine that all the books in the world have been digitised and can be freely searched, allowing even the theft of long-forgotten and weathered ideas. Literature is undoubtedly humanity’s greatest product, but books without catalogues and indexes are merely piles of printed paper. The structural beauty of the literary work expresses a deep truth, yet traditional literature could not say everything that was new. Sometimes truth demands a new form, not merely new content. New technologies intuitively created something that would later be called ‘hypertext’, before the term itself was known. Literary theory had withdrawn into linguistic labyrinths, while pedagogy was turning into a festival of empty meaning. Students write better when they have something to say; they learn languages faster when they want to speak to someone. The new form of truth is knowledge as communication. Beyond being a calculating machine for percentages and dividends, the computer can be a space for adventure, and programming a form of magic. The world of machines is not only models, algorithms and diagrams, but hypertexts, metaverses and interactivity. ‘Metaworlds’ — digital environments in which knowledge can be experienced, not merely read. Language-learning programmes that place learners in real environments — the streets of Rome or neighbourhoods of London. Certain kinds of knowledge live more fully in a digital environment than on paper. The computer does not destroy the book; it is its child — the offspring of five centuries of print culture. The idea of a computer-based literary form is realised in a technology that can make text, image and sound resonate in synchrony. Algorithms can place millions of works side by side, visualise structures that the book itself cannot.

The Future of Cybernarrative

“Stories are our equipment for life; they teach us how to interpret and experience the world.”

— Kenneth Burke

The book Hamlet on the Holodeck (1997) was written in an era of analogue television, printed newspapers and static web pages, when electronic mail still sounded like a plot device from a romantic comedy. And yet the book takes for granted the convergence of media and computer technologies—a process that has since become a global foundation of contemporary culture. The future of narrative in cyberspace is conceived there as a long-term question, extending across decades and even centuries: the formation of new artistic traditions, the emergence of new audiences, and the transformation of science-fiction interfaces into everyday instruments of storytelling. Just as the camera and the printing press once expanded the horizons of human expression, the computer carries its own unique potential for new narrative forms. What begins to take shape is the figure of the future storyteller as a ‘hacker-bard’, experimenting with digital forms—game designers, journalists, filmmakers, television producers, museum curators. Alongside this figure, a conceptual framework for the new landscape also emerges. Simulations, open game worlds, systems of automated storytelling and interactive television appear as extensions of an ancient human activity: narration itself. The computer does not replace storytelling; it expands its expressive repertoire.

In the 2016 foreword, Janet Murray dismisses claims that the digital environment destroys the silence and spiritual depth of reading as convenient rhetorical gestures—nostalgic, but ultimately unsustainable. One can read even the most elevated book superficially, just as one can think deeply in front of a screen. The internet has brought an unprecedented expansion of access to knowledge, along with new digital forms such as simulations, navigational structures and faceted search. These enable new modes of comparison, experimentation and thinking that resemble the complex logic of consciousness more closely than the linearity of the book. Another group of critics, drawn from postmodern theory, argued that the future of electronic literature lay in hypertext. Yet the book does not ask to be read as a late twentieth-century literary theory. It is a manifesto for aesthetic practice and therefore does not share the postmodern desire for endless problematisation. Its interest lies in the future rather than in the crisis of the sign—in the possibility that digital media might generate a more flexible and integrative way of thinking about human experience. Game Studies, also known as ludology (from *ludus*, ‘game’, and *-logia*, ‘study’), constitute the scholarly investigation of games, the act of play itself, and the cultures, communities and practices that form around them. This field within cultural studies examines all types of games across human history. Not all games are narratives, and no ‘narrative hegemony’ can be imposed on game formalism. The power of play is not a threat to storytelling; it is part of the cultural logic from which storytelling itself emerges. Games, like novels and films, can be read as cultural artefacts saturated with meanings, emotions, identities and ideologies. Over time, the old divisions have gradually eroded. Defenders of print began publishing online, hypertext theorists embraced games, and former ludologists turned towards narrative.

Mastery of technology and even the most complex hardware is not sufficient if one does not also master narrative itself—that software of human emotion through which history preserves the names of its creators. Civilisation does not ultimately remember machines, but stories about how they were used and what traces they left on human lives. One may be a brilliant computer programmer, yet fail to inscribe one’s name in history without telling a story, while others are remembered despite never having written a single line of code. In the twenty-first century, people want to create stories that can exist only in a digital environment—stories in which the reader is a participant and the structure is a living organism. Year after year, narratives become bolder, more skilful, more open in dialogue with the machine. Observing them, one senses the birth of a new kind of storyteller—half hacker, half bard—combining technical ingenuity with the ancient human impulse to give meaning to chaos. This is the future of cyberliterature: a form that will not replace the novel or the film, but will extend their capacity to suspend time, to pursue consciousness, to depict the chaos of society. The computer can continue the work of the book: to organise the world not through fixed pages, but through dynamic spaces in which knowledge unfolds as movement. In a time of historical transition, literature is as vital as information technology. Children grow up in a world where screens are as natural as books. Being at home in these environments, they expect the next wonder. How might this wonder be imagined? Janet Murray imagines cyberdrama: a new space born from the spirit of the hacker and the heart of the bard—a space worthy of the imagination that comes after us.

Hyper-Beauty, Cyber-Truth

"Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral."

— Melvin Kranzberg

The holodeck technology of Star Trek still appears distant, while the first digital games, labyrinths, and early websites only lightly touch the expressive potential of the new medium. According to Janet Murray, these early experiments awakened a new kind of desire—especially among the young—for stories one does not merely watch but enters: stories offering deeper immersion, a stronger sense of agency and choice, and prolonged inhabitation of a kaleidoscopic world. Even though the tools remain rudimentary, many people are already creating their own worlds in MUD environments or constructing levels for games with open architectures. For those who do not program, the preparation of digital text, sound, and video is becoming increasingly accessible through standard AI software. Website design gradually turns into an activity as routine as once was making a business card or a greeting card on a home computer. Anyone who masters keyboard and mouse can now create basic pages, links, and visual elements and release them into the network. The World Wide Web becomes a global autobiographical project—a gigantic illustrated magazine of personal stories and opinions. Independent digital authors use the web as a worldwide channel for ‘underground’ creativity: illustrated narratives, animations, hypertext novels, short digital films. Science fiction and fantasy remain powerful, but the mass of family albums, travel diaries, and visual autobiographies steadily pulls digital narrative toward the cultural centre rather than the periphery. At the same time, media conglomerates approach digital space as a new distribution channel rather than a new art form. For them it is simply another ‘pipe’ carrying content to a new market. They move cautiously, most often attempting to ‘make film and television interactive’ without understanding what people actually seek in a digital environment. As a result, future forms of digital narrative will be shaped by the tension between two poles: small, agile experimenters accustomed to hypertext, procedural thinking, and virtual environments, and massive entertainment corporations with resources and mass audiences. Over the coming decades, a variety of formats can be expected, all searching for a balance between the pleasures of linear storytelling and the specific affordances of the digital medium. Viewing habits are changing: people watch a series while simultaneously writing in chats and forums, discussing characters, inventing alternative scenes, criticising screenwriters. Watching and participating slide into one another.

Alongside collective experiences, however, there will also be solitary ones—‘desktop’ digital worlds that one enters alone in order to become the protagonist. Such an environment may be based on a film, a novel, or a historical period, offering multiple scenarios, roles, and choices, and allowing replay until no corner remains unexplored. This form inherits the intimacy of the novel: immersion in an alternative ‘self’, without real-world consequences but with powerful inner transformations. All these variations—hyper-serial worlds, mobile films, role-playing universes, private desktop stories—can be gathered under the provisional name ‘cyberdrama’. This does not signify a new prefix added to the old novel or film, but a gradual rebirth of the very idea of narrative within a digital environment. At first, children and young people will be most strongly drawn to it, as they naturally move from shooters and arcades toward more complex role-playing forms. Over time, however, the format itself will mature; users accustomed to participation rather than observation will demand subtler, more intelligent stories worthy of serious experience and reflection. At a certain point, the medium that today appears intrusive and conspicuous will begin to ‘melt away’. People will stop asking whether they are interacting with a real actor, another participant, or a programmed agent; whether the environment is a filmed set or generated graphics; whether it is delivered by cable or wireless network. Attention will return to where it has always resided in powerful stories—to the narrative itself, to the scene, to moral choice, to the human encounter. And when one forgets the medium and simply lives within the fictional reality, without questioning how it is made, then—even without replicators or perfect holograms—one will find oneself at home on the holodeck.

In this new era, the hero of the media scenario will be at once an omnipotent participant and the most vulnerable inhabitant of cyberdrama—a person who traverses infinite digital universes yet must alone bear the weight of their moral choices. Within this magnificent but controllable cosmos, however, the danger of loneliness will always lurk: no one will ever be entirely certain whether they are facing another human being or an impersonal algorithm, and this uncertainty will turn authenticity into the rarest virtue of future storytelling. According to Zygmunt Bauman, we live in an age of the endless ‘self’, continuously projected outward and perpetually seeking recognition it no longer knows how to trust. Hyper-beauty and cyber-truth mark the moment when digital narrative ceases to imitate the world and begins to rethink it from within—as a mirror that no longer reflects, but creates.

Hamlet and Vedbal in the New Era

‘The word is a weapon. Whoever masters it can destroy and can build.’

— Hristo Smirnenski "Vedbal"

‘There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.’

— William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II, Scene II

Hristo Smirnenski enters literature through journalism, and journalism through language. As a refugee child distributing newspapers on the streets of Sofia, he discovers early on that words are not ornament but action: they can gather crowds, change moods, accelerate the rhythm of the city. Between this early ‘reportage’ and the mature poet stands the figure of Vedbal—the humorist who turns language into a mobile instrument of social intervention. This trajectory is charged with energy, transformation, and initiative—everything that is missing from the straight line of Hamlet’s existence as imagined by Vonnegut.

Vedbal masters the most important rule of public speech: to change the world, one must find the exact distance to the listener’s ear. The feuilleton, the epigram, the satirical sketch—published in ‘K’vo da e’, ‘Bulgaran’, and ‘Laughter and Tears’—are not an escape from seriousness, but a form of attack. Laughter disarms power, renders injustice visible, strips away masks. The short, ironic pseudonym Vedbal sounds like an alarm: the text does not remain on the page, but continues to live in everyday dialogue, in slogans, in remarks exchanged on Sofia’s trams. The journalism in which he grows is a stage, not a podium; movement, not sermon. In Smirnenski, this intuition becomes a poetic position. ‘The Tale of the Ladder’ is a diagram of substitution—how a person trades hearing, sight, heart, and memory for an illusory ascent. This is not merely a moral allegory, but a manual of professional hygiene for words. ‘Guard your hearing’ means: hear the pain beneath the anthem. ‘Guard your eyes’: see the wound behind the ceremony. ‘Guard your memory’: do not forget where you come from and for whom you speak. ‘Guard your heart’: do not turn human tragedy into a convenient effect.

Here the contrast with Hamlet becomes decisive. In Vonnegut’s graph, the life of the Danish prince is a straight line—events follow one another but do not yield secure meaning. Everything moves in the shadow of ‘perhaps’. Hamlet is a grammar of indecision: he hesitates, interprets, doubts witnesses, signs, himself. In Smirnenski, language does not hesitate but acts. It does not remain in the fog of interpretation, but enters the situation and changes it. If Hamlet is ‘thinking to the point of paralysis’, Vedbal and Smirnenski are ‘thinking through movement’. This does not mean that Smirnenski is free of doubt. On the contrary—his poetry often radiates pain, a sense of misery, a gap between dream and reality. But he transforms doubt into impulse, not paralysis. The rhythm of the city, the deadline of the newspaper, the insistence of the street teach him to think scenically: to arrange scenes, shift focus, create montage. The newspaper text becomes direction; the satirical couplet, a striking shot; the poem, a wide-angle view of the social landscape. This is his ‘anti-Hamlet’ method: composition serves not contemplation, but the community. Language for him is neither slogan nor closed canon. It is a living house that comes alive only when its entrance is open. In the satirical texts this house is noisy, overcrowded with voices. In the poetry it is wide, permeable, filled with light and compassion. The idea of ‘language as an empty house that must be inhabited’ is among the most precise summaries of Smirnenski: speech has meaning only when it reaches the other.

From here emerges the difference between Hamlet’s literary model and Vedbal’s journalistic one. Hamlet is fixed in doubt; Vedbal in intervention. Hamlet asks what events mean; Smirnenski asks what must be done. Vonnegut’s straight line marks the fear of banality—of life without form. Smirnenski’s language is the answer: form can be created through action, through speech, through solidarity. This is why the figure of Vedbal remains especially valuable. It reminds us that humour and poetry are not escapes from reality, but ways of naming it, gathering it, addressing it. In a world where Hamletian indecision is often presented as intellectual virtue, Smirnenski proposes another model: a language that does not fear becoming movement, becoming stage, becoming encounter. In this sense he is anti-Hamlet—not because he does not know pain, but because he refuses to submit to it. Language, Smirnenski insists, is alive only if it reaches the other. And perhaps this is the most important lesson in the contrast between Hamlet and Vedbal: when life collapses into a straight line, words can restore its depth.

The Journalist of the Twenty-First Century

‘Journalism allows its readers to witness history; fiction allows them to live it.’

— John Hersey

In the book Journalism of the Twenty-First Century, the profession is examined as a field in collapse and reinvention, yet behind the structures, platforms, and models lies a simpler truth: journalism is not an institution, a market, or a ‘media system’, but an action performed by a concrete human being. All the crises of the system condense into a single figure—the journalist who, in the twenty-first century, must make moral decisions under conditions of permanent uncertainty. If the previous century could rely on newsrooms as stable apparatuses, today it is the individual author who becomes the site where it is decided whether a news item will be testimony or manipulation, whether language will serve the community or power.

The digital revolution has made the journalist simultaneously freer and more vulnerable. Algorithms and platforms have transformed the environment, but the moral choice—what to publish, how to judge a fact, how to endure pressure—remains personal. In a world of endless information flows, the journalist can no longer hide behind an ‘editorial line’, because their name, face, and voice are visible in social networks, and every word is subject to public contestation. Professional identity is no longer shielded by institutional walls; the journalist is exposed as an autonomous participant in public life. This exposure brings new responsibilities. The twentieth-century model, grounded in objectivist myths—the ‘view from nowhere’, the ‘transparent observer’, the ‘impartial witness’—has collapsed. In the digital environment, the journalist cannot simply present themselves as a neutral apparatus; audiences expect sincerity, argument, and position, but also honesty about one’s own limitations. Objectivity is no longer a role but a practice: a sustained effort toward accuracy, verification, openness, and self-restraint. In this sense, the journalist of the twenty-first century is less a ‘figure of authority’ and more a ‘figure of personal responsibility’.

The journalist’s working process has also changed beyond recognition. Today, the journalist is writer, photographer, camera operator, producer, editor, social media manager, and often their own publicist. In this single figure collide the contradictions of the age: the desire for high-quality, verified information and the demand for rapid content production; the pursuit of independence and dependence on algorithms that measure value through clicks and views. The individual stands between two systems—the system of truth and the system of visibility—and must choose daily which one to serve. The journalist of the twenty-first century operates under constant moral friction. Advertising models erode the boundary between editorial and sponsored content; the PR industry offers ready-made ‘stories’; political pressure disguises itself as ‘communication’; corporate interests impose constraints; online audiences punish complexity and reward sensation. In such an environment, every publication is a decision. Should one use fast, unverified information? Should one accept an ‘exclusive’ that clearly serves someone’s interest? Should a headline be distorted to retain attention? Professional ethics no longer have a collective form; they reside in the journalist’s private ‘no’.

At the same time, the public sphere has filled with voices that challenge the legitimacy of professionals. The smartphone has turned every witness into a potential chronicler, and social networks into mediators of publicity. Yet however valuable these new sources may be, they do not eliminate the role of the journalist as a figure capable of connecting facts, verifying claims, placing events in context, and confronting power. The difference between reporting and noise is that reporting carries responsibility. And responsibility is personal, unavoidable, and non-transferable. Thus, the key change of the twenty-first century is not the destruction of journalism, but the rewriting of the journalist’s role. The journalist is no longer a gatekeeper—there are no gates. Not the voice of the people—the people speak for themselves. Not an ‘objective guarantor’—objectivity is contested in real time. The journalist is something more modest and more difficult: a person who works with words to create space for meaning in an environment that produces noise; a person who preserves their hearing in order to distinguish fact from falsehood; a person who arranges scenes so that society can see itself without self-deception.

The journalist of the twenty-first century is a figure in a process of continuous self-discovery. Their strength is not institutional but moral; it does not come from circulation figures but from the capacity to be present; it is not measured in views but in the degree of honesty one can endure. In a fragmented, digital, and often hostile world, the journalist remains the last living knot between events and public meaning. And precisely because the world of news is disintegrating, the figure of the journalist is more necessary than ever—not as a hero, but as a human being who protects language from becoming an instrument of forgetting. The journalist of the twenty-first century is not called to be a fictional person who fabricates human fictions, but an authentic person who preserves their truthfulness even when the surrounding world demands convenient and well-paid stories. The most interesting element of the media scenario is the emotional arc of the protagonist, but the most important is the character of the author. The journalist is called to unite both roles.

‘All I ever wanted was to go there, see what was happening, and tell the truth to people.’

— Martha Ellis Gellhorn (1908–1998), American writer and journalist, war correspondent who covered most of the major armed conflicts from the late 1930s to the 1980s.

Conclusion

Vonnegut’s intuition that stories have ‘shapes’ simple enough for computers to recognise turns out not to be a joke about technology, but a sober observation about human culture. Stories repeat because human experience repeats. The movement between hope and loss, ascent and collapse, recovery and uncertainty constitutes a minimal grammar of meaning through which people make life intelligible. When algorithms detect these patterns, they do not reduce literature to data; they reveal how deeply narrative form is embedded in cognition, emotion, and social behaviour. Computers understand stories because stories are already structured like processes: sequences of transitions that mirror how humans experience time, expectation, and disappointment. Yet the recognition of these shapes does not exhaust narrative meaning. Vonnegut’s graphs capture rhythm, not truth; motion, not value. A rise on the curve does not tell us what ought to rise, nor does a fall explain why suffering occurs. The danger lies not in recognising patterns, but in mistaking them for destiny. When media, politics, and platforms endlessly reproduce the same emotional arcs, narrative ceases to be a tool for understanding and becomes an instrument for conditioning expectation. Crisis, recovery, and catharsis begin to feel mandatory rather than meaningful. The world is experienced not as lived reality but as a script awaiting its next turn. Vonnegut’s most radical insight lies in his insistence on indeterminacy. The straight line of Hamlet, the refusal to label events as definitively good or bad, exposes the gap between life and its narrative representations. This gap is where ethical responsibility resides. Stories simplify so that humans can endure existence, but they also risk concealing complexity, ambiguity, and responsibility. Awareness of narrative shape therefore becomes an ethical task: to know when a curve clarifies experience and when it falsifies it; when it liberates imagination and when it imprisons it within pre-written roles. In the age of algorithmic storytelling, emotional analytics, and media scenarisation, Vonnegut’s diagrams acquire renewed urgency. They teach not how to manipulate attention, but how to recognise when attention is being guided by familiar forms. To understand that even computers grasp stories is to understand something unsettling about ourselves: that humans, too, are vulnerable to the comfort of simple curves. The task is not to abandon storytelling, which is impossible, but to regain agency within it. By recognising the shapes we live by, people may recover the freedom to bend them, interrupt them, or refuse them altogether. Narrative remains unavoidable, but it need not remain invisible.

Epilogue

This book is not written to train future specialists in how to manipulate the masses, predict the future, instruct society, or point fingers at the mistakes of the past. It is not a manual for PR professionals, journalists, or aspiring experts in influence. It is an attempt to understand what happens to the human being in an environment where narratives are no longer lines but scenarios; where they do not unfold before one’s eyes but absorb the individual entirely. And what happens to ‘us’—insofar as such a ‘we’ can exist at all in an age of disintegrating communities and hyper-produced identities. For anyone who speaks publicly, sooner or later arrives at the word ‘we’. This word is the most seductive and the most dangerous in the media vocabulary. In its Proto-Slavic root, ‘ve’ means only ‘the two of us’—not a people, not a party, not a nation, not ‘everyone’ (PIE *we-, Sanskrit ‘vayam’, Old Persian ‘vayam’, Hittite ‘wesh’ ‘we’, Church Slavonic ‘ve’ ‘we two’). Every broader ‘we’ is already an extension, a belief, an abstraction, a metaphor—and sometimes an illusion. The excessive use of ‘we’ in politics, media, and science gives rise to the phenomenon known as early as the eighteenth century as ‘wegotism’: the over-inclusion of the reader within the speaker’s circle, the pretence that everyone thinks, feels, and believes the same way. The central danger of the media scenario lies precisely here: not in manipulation, but in ‘seduction through belonging’. The ‘I’ approaches the reader, touches them, inscribes them into its own perspective, and then suddenly withdraws back into distance. An ‘I’ that both invites and refuses; a ‘we’ that both unites and erases differences; a narrator who alternates between the role of protagonist and that of a cold observer. In this game of approach and retreat, the power of the first person is born—and its poison. The journalist of the twenty-first century can no longer ignore this dynamic. Their primary task is no longer ‘to tell the truth’, because truth itself dissolves at the entrance to every network; nor is it ‘to educate’, because audiences often know more about their own lived experience; nor is it ‘to protect society’, because society has fragmented into countless small ‘we’s. The first task of the ‘new journalist’—the digital bard—is to know who they are, where they stand, from which position they speak, and which community they represent, even if that community is the minimal ‘we two’: the speaker and the addressee. Here Kurt Vonnegut becomes especially important. His ‘curve’—that famous graphic model of rises and falls—is not merely a tool of plot. It is a diagram of human vulnerability. Every narrative, even the smallest one, is a change over time: a point that rises or falls according to the hopes, fears, and moral choices of the narrator. In the digital era, this curve is no longer linear, no longer individual, no longer the property of the author alone. It fragments into multiple micro-arcs drawn simultaneously by different participants—journalists, algorithms, users, trolls, bots. No one holds the ‘pen’ alone. That is why the media scenario of the new age cannot be studied merely as a technique. It must be understood as an environment in which people live, construct identities, lose orientation, and seek belonging. This book does not teach how to write a scenario; it teaches how to recognise when you are already inside a scenario you did not write. How to become aware of the role you are playing without intending to. How to find your place on a stage prepared by someone else. And most importantly—how not to lose your moral compass. Because the greatest danger is not lies, not propaganda, not manipulation, but cynicism: the moment when one begins to believe that words mean nothing and that ‘we’ is merely a convenient rhetorical device for binding an audience together. The media scenario of the future will be neither utopian nor post-historical, post-truth, or dystopian. It will be pluralist. Multiple realities will unfold simultaneously, each with its own logic of participation. The journalist will be neither director nor mere witness, but a mediator between versions of the world. And they will remain the only one who must remember that behind every ‘we’ stands a human being, not a crowd; a relationship, not a demographic; a personal choice, not a collective destiny. The paradox of our time is that the more technologies allow us to speak to everyone, the greater becomes the responsibility for how we construct the communities we summon with our words. Every use of ‘we’ is both a promise and a risk. That is why this epilogue is an invitation to sobriety: before creating a ‘we’, one must know what kind of character one is; before writing a scenario, one must realise in what genre of scenario one is already participating; before becoming a journalist, one must be prepared to stand behind one’s words as a human being. Because at the end of every media narrative, game, or scenario—beyond cameras, networks, algorithms, and illusions—there remains only one real ‘we’: the fragile, human, uncertain, unrepeatable ‘we two’ that makes storytelling possible. And only through it can a story be moral, and a journalist free.

Bibliography

Ayolov, P. (2026). The New Paradigm of Mass Communication. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5998697.

Ayolov, Peter (2026) The Media Scenario: Scriptwriting for Journalists eBook: Kindle Store. Amazon.com: [online]

Vonnegut, K. (1947). The Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tasks. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Chicago.

Reagan, A.J., Mitchell, L., Kiley, D., Danforth, C.M. and Dodds, P.S. (2016). The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six basic shapes. EPJ Data Science, 5(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-016-0093-1.

Vonnegutreview.com. (2025). Fictional Humans and Humanist Fictions. [online] Available at: http://www.vonnegutreview.com/2013/09/timequake.html [Accessed 17 Oct. 2025].

Case Western Reserve University (2016). Kurt Vonnegut Lecture. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_RUgnC1lm8.

Murray, J.H. (1997). Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hardy, J. (2021). Journalism in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.