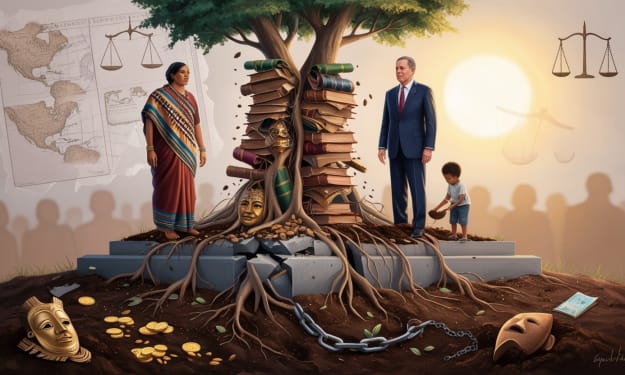

History, Identity, and Power: Who Gets to Write the Truth?

National myths, contested identities, and the global politics of memory.

History is not merely a record of what happened. It is a powerful tool, shaped by those who write it, often reflecting the agendas, traumas, and aspirations of nations. In our post-colonial world, history is contested terrain. Nowhere is this more evident than in the ongoing debate over the origins of the Jewish people, the identity of modern Israelis, and the broader question of who has the right to claim historical legitimacy.

This article does not question anyone's humanity or faith. Instead, it asks: How have modern national identities been constructed? And what are the consequences when myth, memory, and politics intertwine?

Constructing Identity: The Case of Modern Israel

The modern state of Israel, founded in 1948, emerged from a complex web of religious longing, European nationalism, colonial geopolitics, and trauma, especially the Holocaust. Zionism, the movement advocating for a Jewish homeland, gained traction among European Jews in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in Eastern Europe, where anti-Semitism was widespread.

Many early Zionist leaders, including David Ben-Gurion and Theodor Herzl, were secular European Jews who spoke Yiddish, German, or Russian. Hebrew, long dormant as a spoken language, was revived as a national language through conscious political effort. As scholar Ilan Pappé notes, this was part of a broader "ethnic engineering" project—one not unlike similar processes in other postcolonial or settler-colonial states (Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, 2006).

The Khazar Hypothesis: A Contested Theory

One controversial idea, made popular by journalist and historian Arthur Koestler in his 1976 book The Thirteenth Tribe, argues that Ashkenazi Jews (many of whom migrated to Israel) descend not from the ancient Israelites but from the Khazars, a Turkic people who converted to Judaism in the 8th century CE. Koestler’s intent was not malicious—he sought to reduce anti-Semitism by disrupting ideas of racial purity.

However, most genetic studies and historians today dispute this theory. A 2013 genetic study published in Nature Communications by Doron Behar and colleagues found that Ashkenazi Jews show strong Middle Eastern genetic markers, though with admixture from Europe. The consensus is that while Jewish communities have migrated and mixed over centuries, they maintain deep historical ties to the Levant.

Identity and Power: The Politics of Naming

Names carry weight. To rename oneself or one’s city, as has happened across modern Israel and Palestine, is not simply a cultural act—it is a political one. This is seen in the Hebraization of European surnames among early Israeli leaders (e.g., David Grün to David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meyerson to Golda Meir).

This phenomenon is not unique to Israel. Across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, colonized and post-colonial societies have wrestled with names, languages, and memory. In South Africa, colonial names still mark landscapes even as indigenous names are slowly restored. In the United States, debates rage over Confederate monuments and street names. Everywhere, history is edited through symbols.

Memory, Myth, and Modernity

All modern nations tell stories about their past. These stories often blur fact and faith, memory and mythology. The Bible, for example, is both a religious text and a historical source—but it is not a neutral one. Its narratives have been used to justify conquest, migration, and divine right.

The tension arises when religious narratives are used to legitimize contemporary political actions—such as settlement expansion, land expropriation, or war. As scholars like Edward Said have warned, using myth as a basis for modern policy risks erasing the rights and voices of others, particularly Palestinians who also claim deep roots in the land (Said, The Question of Palestine, 1979).

The Right to Question

In many societies, questioning official narratives comes at a cost. Those who ask difficult questions are accused of betrayal, denialism, or even anti-Semitism. But to question is not to hate. It is to seek clarity in a world clouded by propaganda, trauma, and fear.

History must be a conversation, not a monologue. No group should be above accountability. Likewise, no population should be collectively blamed for the actions of a few. The goal is not to deny anyone's right to exist, but to create space for honesty, justice, and reconciliation.

Toward a More Honest Future

We cannot build a just world on foundations of selective memory. Whether we are discussing Israel-Palestine, colonial Africa, or indigenous land rights in the Americas, we must confront how history is written, and who benefits from its erasures.

It is not enough to expose lies. We must also repair the damage they have caused—through dialogue, truth-telling, and policy.

The truth is complex. It may never be complete. But only by facing it can we begin to heal.

Sources:

- Arthur Koestler, The Thirteenth Tribe (1976)

- Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (2006)

- Edward Said, The Question of Palestine (1979)

- Doron Behar et al., Nature Communications (2013)

What do you think? Is it possible to reclaim truth in a world built on competing memories? Let’s have the conversation.

About the Creator

David Thusi

✍️ I write about stolen histories, buried brilliance, and the fight to reclaim truth. From colonial legacies to South Africa’s present struggles, I explore power, identity, and the stories they tried to silence.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.