The Banality of Evil in Terrence Malick’s 'Badlands'

Terrence Malick’s Badlands turns the Charles Starkweather murders into a chilling meditation on the banality of evil. This review explores how Malick’s vision inspired Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska and stripped Hollywood violence of its illusions.

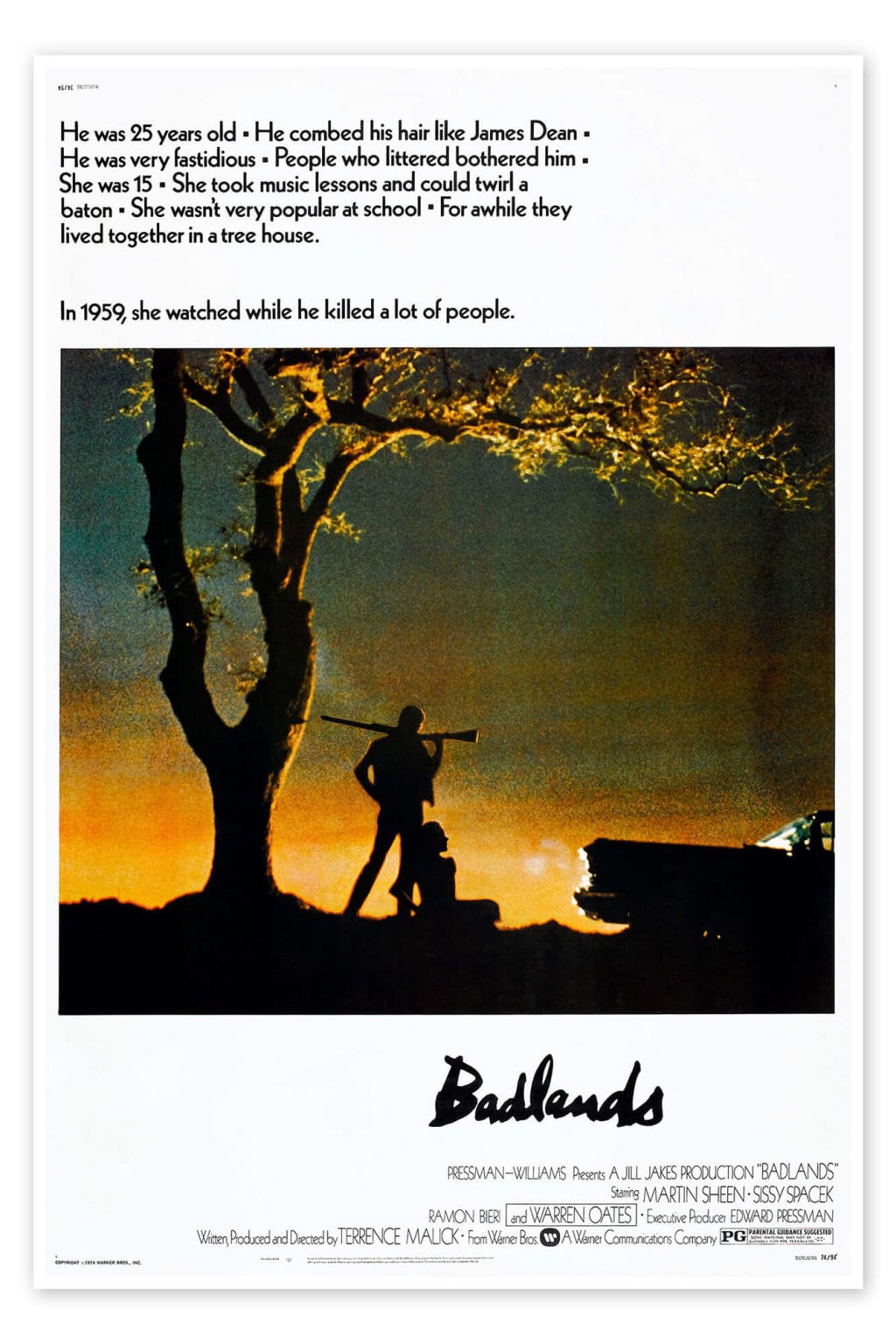

Badlands

Directed by: Terrence Malick

Written by: Terrence Malick

Starring: Martin Sheen, Sissy Spacek, Warren Oates

Released: October 15, 1973

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️½ (4.5/5)

Terrence Malick’s Badlands turns the Charles Starkweather murders into a chilling meditation on the banality of evil. This review explores how Malick’s vision inspired Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska and stripped Hollywood violence of its illusions.

The Banality of Evil Comes to the American Frontier

Philosopher Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” in 1963’s Eichmann in Jerusalem to describe Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann’s frightening normalcy. Eichmann defended his role in the Holocaust by insisting he was “just doing his job.” His tone—methodical, bureaucratic, disturbingly ordinary—suggested that true evil often hides in plain sight, wearing the mask of routine.

Ten years later, Terrence Malick applied this same observation to America’s own brand of quiet horror: the 1958 killing spree of Charles Starkweather. In Badlands, Starkweather becomes Kit McCuller (Martin Sheen), a garbage man who drifts into murder as casually as one might clock in for work. His violence isn’t driven by rage or ideology—it’s performed with the dispassionate rhythm of habit.

⸻

Violence Without Style or Comfort

Malick refuses to dress Kit’s crimes in the cinematic language of thrillers. There are no music cues warning of danger, no stylish editing to excite or distance us. Instead, Malick presents the murders plainly, as if to remove our ability to rationalize or compartmentalize them.

Even the music feels alien—detached, hauntingly neutral. It doesn’t underline the violence but underscores the emptiness that drives it. Through this stripped-down presentation, we are forced to confront Kit and Holly (Sissy Spacek) as they are: two young, emotionally vacant people fumbling through identity and desire.

Kit, a veteran of the Korean War, has learned to see death as ordinary. Life, to him, holds meaning only when it serves his wants—freedom, love, a fleeting sense of importance. Holly, alienated by her father (played with understated ache by Warren Oates), becomes an accomplice through her own numbness. She is fifteen, naive, and conditioned by loss to accept absence as normal.

⸻

How Badlands Inspired Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska

Malick’s portrait of moral vacancy and emotional distance directly inspired Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 masterpiece Nebraska. Like Malick, Springsteen was captivated not by Starkweather’s acts but by the emptiness behind them.

Where Kit externalizes his pain—turning it outward into violence—Springsteen internalizes it. The killer in “Nebraska” becomes a metaphor for Springsteen’s own fears: the isolation, boredom, and quiet despair that can curdle into something monstrous.

In Badlands, Kit’s crimes stem from a lack of meaning. In Nebraska, Springsteen channels that same lack into art—a cry from a man staring into the void and choosing to create instead of destroy.

⸻

Malick’s Uncomfortable Mirror

Terrence Malick critiques the way movies traditionally sanitize violence. Hollywood thrillers create a safe distance between us and brutality through style and spectacle. Badlands does the opposite. It collapses that distance, presenting Kit as an unsettlingly familiar figure.

He’s not a horror-movie monster. He’s a charming young man, lazy, selfish, dangerously ordinary. Malick repeatedly frames Kit and Holly against vast South Dakota and Montana skies—landscapes so beautiful they feel complicit in the horror. The message is clear: these people, this violence, exist in the same breathtaking world we do.

⸻

The Horror of Chance

What makes Badlands unforgettable isn’t just its aesthetic restraint but its moral chaos. Kit’s murders have no purpose, no pattern, no grand design. He kills because he happens to, because a moment tilts that way.

That randomness is what terrifies us. Evil here isn’t the product of destiny—it’s the byproduct of chance. The same way Eichmann happened to find purpose in bureaucracy, Kit happens to find his in murder.

It’s the haunting suggestion that we survive not through divine order, but through accident—the arbitrary mercy of someone else’s choice not to pull the trigger.

⸻

Final Thoughts

Badlands remains one of Terrence Malick’s most haunting achievements. It dismantles our cinematic comfort zones, exposing how ordinary the machinery of evil can look when stripped of spectacle.

Through Kit and Holly’s empty pursuit of freedom, Malick reminds us that beneath the beauty of America’s badlands lies something darker—the terrifying possibility that meaning itself is an illusion.

⸻

Tags:

Terrence Malick, Badlands review, Bruce Springsteen Nebraska, Martin Sheen, Sissy Spacek, Charles Starkweather, American cinema, 1970s movies, I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast, film analysis

About the Creator

Sean Patrick

Hello, my name is Sean Patrick He/Him, and I am a film critic and podcast host for the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast I am a voting member of the Critics Choice Association, the group behind the annual Critics Choice Awards.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.