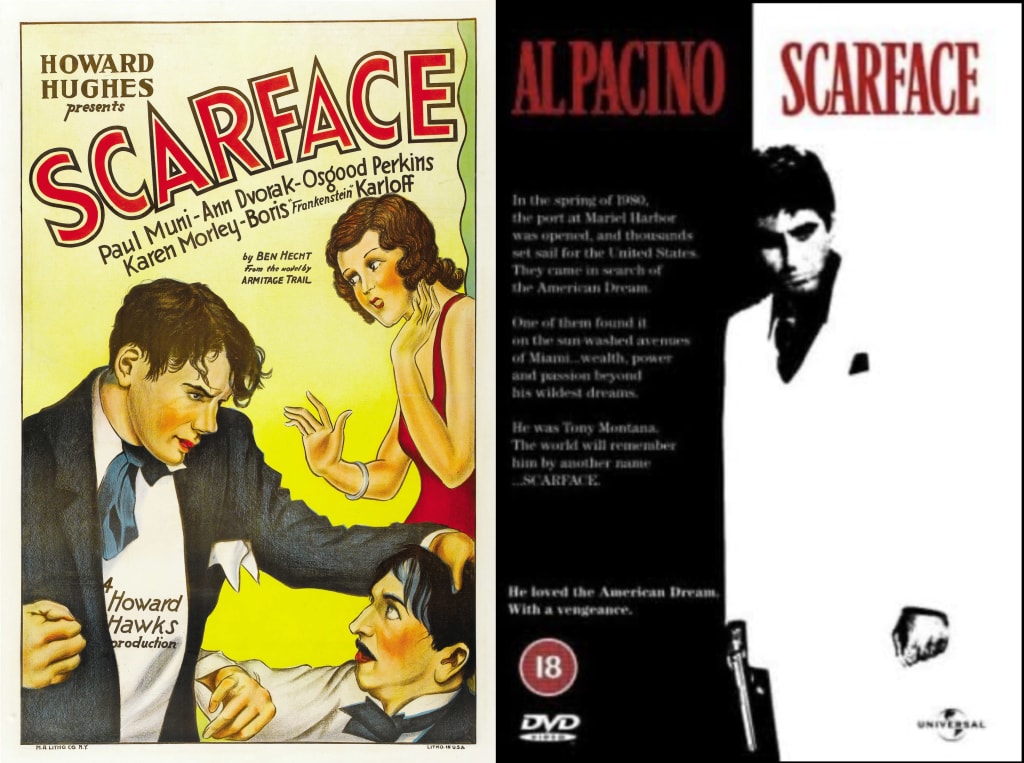

Scarface 1932 vs. Scarface 1983: Two Gangsters, Two Americas

A side-by-side comparison of Scarface (1932) and Scarface (1983), exploring how two very different gangster films reflect the anxieties, ambitions, and cultural pressures of their eras—from Prohibition to the cocaine-soaked 1980s.

Two Scarfaces, Two Americas

The 1932 Scarface arrives in the middle of the Prohibition era, when newspapers obsessed over Al Capone and the public devoured gangster headlines the way we devour celebrity feuds. Howard Hawks and producer Howard Hughes made a film that felt like overhearing the city’s dirtiest gossip whispered through a dictionary of bullets. It’s blunt, fast, and sharp—almost breathless in the way it barrels through Tony Camonte’s rise and fall.

The 1983 Scarface is something else entirely. Brian De Palma and Oliver Stone weren’t trying to recreate Hawks; they were trying to recreate the moment. Miami in the early 80s was ground zero for cocaine trafficking, a city that overwhelmed the senses—neon colors, Latin music, bodies moving fast, money moving faster. If the 1932 film is a newspaper headline, the 1983 film is a fever dream.

Both stories are about a criminal outsider chasing the American Dream. But the country Tony Camonte wanted and the country Tony Montana wanted are almost unrecognizable from one another.

Tony Camonte vs. Tony Montana

Paul Muni’s Tony Camonte is a creature of impulse and intimidation. There’s an almost reptilian stillness to him—he watches, he calculates, and he strikes. His world is small: a boss, a turf, a sister he guards with a corruption of love.

Pacino’s Tony Montana is the opposite. He’s all volume, all posture, all relentless forward motion. He doesn’t just want success; he wants more than whatever anyone else has ever had. He’s the immigrant who refuses to assimilate, the man who believes the rules were written to keep him small. His violence isn’t cold-blooded calculation—it’s volcanic, emotional, operatic.

One is a gangster molded by Chicago’s shadows. The other is a gangster shaped by Miami’s sunburned chaos.

Yet both men are bound by the same fatal instinct: if they’re not climbing, they’re dying.

Two Visions of Violence, Two Cinematic Languages

Hawks used violence as punctuation. A burst of gunfire, the sudden rattle of a Tommy gun, the quiet shock of a body hitting the floor. It was still shocking in 1932 because the Production Code hadn’t fully descended yet, and the movie pushed against whatever flimsy rules existed at the time.

De Palma turned violence into visual opera. The chainsaw scene, the nightclub shooting, the final assault—these moments aren’t just set-pieces. They’re crescendos. He pushes the camera, the colors, and the sound until the brutality becomes overwhelming, almost grotesquely beautiful in its excess. It’s not realism; it’s spectacle, and deliberately so.

The 1932 film wants to show you how violence destroys a city.

The 1983 film wants to show you how violence destroys a man.

What Each Film Says About the American Dream

Every version of Scarface is a tragedy, but the tragedies come from different cultural wounds.

The 1932 film is a warning about unchecked ambition in a country trying to rebuild moral order. It’s the story of what happens when a man uses chaos as a ladder.

The 1983 film is the story of an immigrant chasing a dream that never really existed. It’s capitalism rewired as a survival instinct, success measured only by acquisition, and destruction treated as a sign of power. Tony Montana doesn’t just want America—he wants to bend America to his will.

Both films say the same thing in the end: if the dream becomes the only thing you see, you’ll never notice the cliff you’re about to walk off.

Scarface’s Legacy: Iconography and Misinterpretation

The 1932 Scarface became the skeleton key of the gangster genre. Its fingerprints are everywhere—from film noir to modern crime thrillers. It’s studied, respected, and treated the way we treat old crime photographs: sharp, cold, and essential

The 1983 Scarface became something stranger. It became myth. A poster on dorm-room walls. A mantra for ambition. A symbol embraced by people the movie was actively warning against. What was meant as a tragedy somehow became a lifestyle brand. That misreading tells its own story about the culture that adopted it.

Both films were shaped by fear—fear of crime, fear of outsiders, fear of the country losing control of its own story. And both films became mirrors instead. Each version of Scarface reflects back exactly what its era refused to admit: that the American Dream, at its most feverish, is a story of wanting more than you can hold and believing you’ll be the first one in history strong enough not to burn your hands.

Final Word: Two Versions, One Warning

In the end, the power of Scarface lies in its repetition. Two films made half a century apart arrive at the same brutal truth: ambition without limit becomes annihilation. Tony Camonte and Tony Montana are separated by culture, by history, by the look of their cities and the sound of their violence, but their downfall is identical.

They dream in different accents, but they die in the same language.

That’s why Scarface endures—not because it glorifies the climb, but because it understands the fall. The story keeps returning every generation because the warning keeps being ignored. And as long as America keeps producing men who believe the world is theirs, Scarface—in every decade—will remain necessary.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.