Maryland: The Lynching of William Andrews

Most disturbing crime of every state in U.S.A.

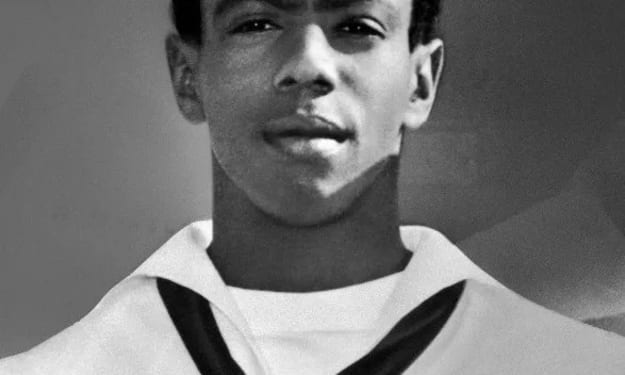

William Andrews was an African American laborer who was lynched by a white mob in Princess Anne, Maryland on June 9, 1897. Andrews, then 17, was tried, convicted, and hanged all in one day after being accused of assaulting Mrs. Benjamin T. Kelley.

In the late 19th century, Maryland was a land marked by deep-seated social divisions. One of the most harrowing episodes during this turbulent time was the lynching of William Andrews, an African‑American laborer, whose tragic fate became a symbol of the racial injustices that plagued the era.

William Andrews, known by some as Cuba, worked tirelessly as a laborer and was recognized for his strong work ethic. Despite his dedication, Andrews’ life was overshadowed by the pervasive racial tensions of his time. In June 1897, following allegations against him in connection with an incident involving a white woman, tensions reached a boiling point. Andrews, who had expressed remorse and attempted to comply with the legal process, found himself at the mercy of a hostile community.

On June 9, 1897, the situation took a dire turn. Following his transfer to Baltimore for what was meant to be a protective measure, Andrews was returned to his hometown for trial. It was there that a large, angry mob gathered outside the courthouse. Despite the efforts of the presiding judge and law enforcement, the crowd’s anger proved overwhelming. In a display of brutality that shocked onlookers, the mob overpowered the limited police force present.

Once the court adjourned, a large mob began to grow outside the courthouse making it impossible for the officers to transfer Andrews to the nearby Somerset County jail. While handcuffed, William Andrews was ripped away from the arms of the officers by an infuriated mob that cheered after hearing a guilty verdict. Andrews was brutally kicked, punched, and beaten with all sorts of weapons until the crowd of people were satisfied. After the crowd realized Andrew Williams was still alive they dragged his body to the property of Z. James Doughtery, where he was hanged on a walnut tree until he was finally pronounced dead. His body remained on the walnut tree until around 2:30 p.m. on June 9, 1897

The violence inflicted upon him was severe, and despite Andrews’ protests and pleas for mercy, the mob carried out a lynching that would forever scar Maryland’s history. The methodical nature of the attack, combined with the public display of violence, underscored the deep racial divides and the failure of the legal system to protect vulnerable individuals.

In the days that followed, the lynching of William Andrews sparked outrage and sorrow among many in the community, yet it also highlighted the systemic failures that allowed such acts of brutality to occur. Although some local officials attempted to quell the public outcry, the incident would become a defining moment in Maryland’s troubled racial history.

For decades, the lynching of William Andrews was a subject of quiet reflection—an event that was both condemned and, in some areas, tacitly accepted as part of the region’s painful past. Historians have since examined the incident as a critical example of the social and legal injustices of the era, emphasizing the need for change and the importance of remembering these dark chapters in history.

The story of William Andrews has since been used by civil rights advocates and educators as a powerful reminder of the need to address racial injustice and build a more equitable society. Memorials and educational programs now seek to honor Andrews’ memory while acknowledging the deep wounds inflicted by such acts of violence.

Today, Maryland continues to grapple with its historical legacy. The lynching of William Andrews serves as a somber lesson on the consequences of unchecked hatred and the importance of upholding justice for all members of society. His story remains a call to action—a reminder that the work of healing and reconciliation is never truly complete.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.