Jack the Ripper: Mystery and Terror in the Streets of Whitechapel

Investigations and Failures: The Struggle to Catch the Killer

In the mid-nineteenth century, the main British boroughs, including the East End of London - where Whitechapel is located - were overpopulated due to the influx of Irish immigrants and the arrival of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe and Imperial Russia from 1882 onwards.2 This problem led to a decline in employment levels and quality of life, and led to the proliferation of a large underclass characterised by poverty, crime and violence, alcoholism and prostitution. According to London Metropolitan Police estimates, in October 1888 there were 62 brothels and 1200 prostitutes in Whitechapel. Also, demonstrations and protests over the economic situation were common between 1886 and 1890, most notably the Bloody Sunday of 1887.1

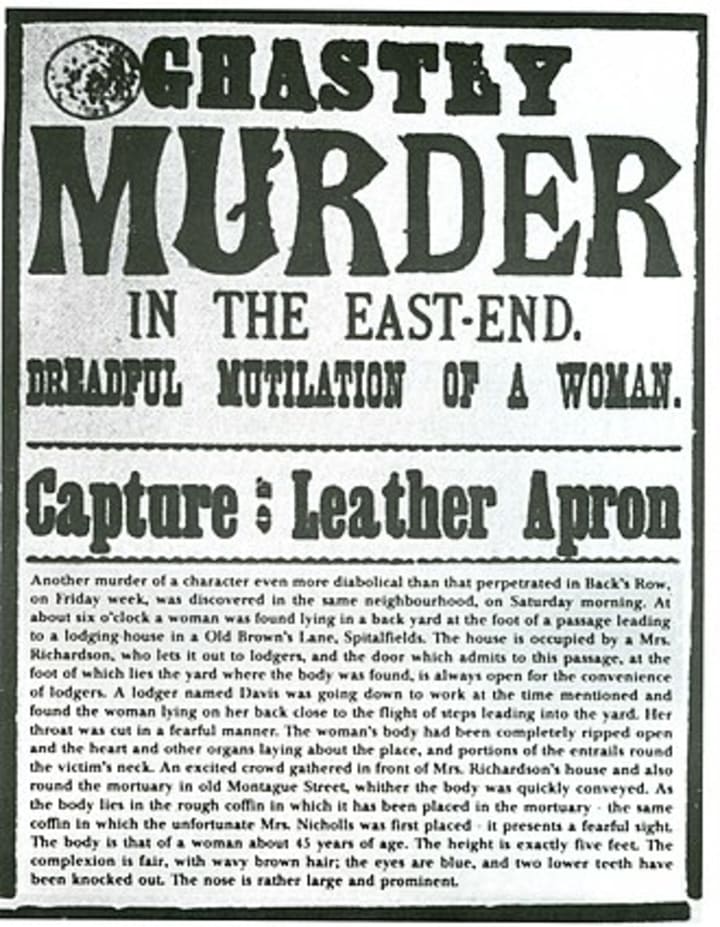

Whitechapel had a particularly bad reputation for anti-Semitism, racism, crime, social unrest and grinding poverty. This perception as a stronghold of immorality came to a head in 1888, when the press began to give unprecedented coverage to a series of grotesque and heinous murders attributed to ‘Jack the Ripper’.

The five canonical murders

Police found the body of the first canonical victim Mary Ann Nichols, at 3.40am on Friday 31 August 1888, in Buck's Row - now Durward Street - Whitechapel. She had a couple of slashes across her throat, her abdomen partially torn with a deep zigzag slit and several incisions made with the same knife.

Annie Chapman's body was found days later, on Saturday 8 September, at approximately 6am, near the entrance to the inner courtyard in Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. She had two slits in her throat, as had Nichols, but in Chapman's case her belly had been completely cut open and eviscerated, with her intestines placed over one shoulder, and her uterus had been removed. A witness claimed to have seen Chapman half an hour before the discovery with a dark-haired man who looked like a "gentleman down on his luck".

The murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes occurred in the early hours of Sunday 30 September; the former's body was discovered at 1 o'clock in Dutfield's Yard - now Henriques Street - and had a cut on the left side of her neck that damaged her carotid artery. However, there were no incisions on his abdomen, which raised doubts as to whether the Ripper was the perpetrator, or whether he had been interrupted during the attack. Although witnesses claimed to have seen Stride with a man earlier, their testimonies were irregular: some said the companion was blond, others dark-haired; and some even claimed he was dressed in tattered clothes, while others argued otherwise.

Forty-five minutes later, police found Eddowes' body in Mitre Square in the City of London. Like Chapman, his throat had been deeply slit, his abdomen had been cut deeply and extensively vertically with evisceration and intestines placed over one shoulder, and his left kidney and most of his uterus had been removed. In addition, her face had been slashed. Joseph Lawende, a neighbour who said he had passed by the street with two friends shortly before the murder, stated that he had seen a woman with a blonde, unkempt-looking man.

Eddowes' bloody apron was found near the entrance to a block of flats in Goulston Street, and graffiti was found on the wall - just above where the garment was - which appeared to implicate a Jew, although it could not be ascertained whether the graffiti had been written by the killer or whether it was merely coincidental, as such illicit writing was common in Whitechapel at the time. Charles Warren, the police commissioner, called for the graffiti to be removed before dawn on suspicion that it might have incited anti-Semitic protests.

Police finally found the atrociously mutilated and totally disembowelled body of Mary Jane Kelly on the bed in her rented room in Miller's Court, Spitalfields, at 10.45am on Friday 9 November. She had a deep cut running from her throat to her spine, her face shredded beyond recognition and all her abdominal organs and heart had been removed.

The five canonical murders occurred at night, usually over a weekend and within a month. It can also be inferred that each murder was more severe than the previous one, except for Stride, whose attack was presumably interrupted. Nichols' body had all her organs, but Chapman and Eddowes had their wombs removed and were disembowelled, while Chapman and Kelly had their faces mutilated.

The link between these five crimes can be traced back to later documents in which they are excluded from other murders. For example, a letter written by the coroner Thomas Bond to the head of the London CID (Criminal Investigation Department), dated 10 November 1888, already lists the five canonical victims. For some analysts, some Whitechapel murders were undoubtedly the work of the same individual, but others involved an unknown number of murderers. Such was the case of authors Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow, who labelled the canonical dossier "the Ripper myth", arguing that while the Nichols, Chapman and Eddowes cases have similarities, there is no evidence that the Stride and Kelly murders were committed by the same person.

There are even those who argue that the Tabram murder does fit the canonical record. Dr Percy Clark, assistant to coroner George Bagster Phillips, concluded that three of the deaths were committed by the same individual, while the rest were the work of "weak-minded individuals ... with conviction to imitate [the original series of murders]". with the conviction to mimic. Although the new head of the CID, Melville Macnaghten, stated categorically in a report that "the Whitechapel murderer had five victims, nothing more", it should be noted that Macnaghten had joined the police a year after the canonical deaths and that his memo included errors in the description of the possible suspects.

Investigation of the murders

The police documents on the Whitechapel murders give an insight into the investigation procedure in Victorian times: to gather information, a large team of officers went from house to house and sounded out neighbours. Forensic material was meanwhile analysed by qualified personnel. When suspects were identified, the investigation was further investigated and, depending on the results, a decision was made to either prosecute or dismiss them from the file. This has been the method used in contemporary police investigations ever since.

In connection with the Whitechapel murders, the police interviewed over two thousand people, investigated approximately three hundred, and arrested eighty. The Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the Whitechapel Metropolitan Police, headed by Inspector Edmund Reid, carried out the investigations into the first two cases in the Whitechapel file. Following Nichols' death, Scotland Yard headquarters sent Inspectors Frederick George Abberline, Henry Moore and Walter Andrews to investigate the case. The City of London Police became involved after the Eddowes murder, through Detective James McWilliam. However, investigations were obstructed because the newly elected CID Commissioner, Robert Anderson, had requested leave from Switzerland between 7 September and 6 October 1888, the period when the murders of Chapman, Stride and Eddowes occurred.

As a result, Charles Warren, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, appointed Donald Swanson as co-ordinator of Scotland Yard's investigations. Dissatisfied with the police effort, a group of citizens from London's East End began patrolling the streets under the moniker of the 'Whitechapel Vigilance Committee', whose aim was to find possible suspects in the murders. In addition to hiring private detectives to interview suspected witnesses, they suggested that the government offer a reward for information about the killer as an alternative way of gathering more information.

Due to the type of injuries of the victims, the police initially considered butchers, surgeons and doctors as suspects. According to a report drawn up by Inspector Swanson and addressed to the central office, 76 butchers' shops and slaughterhouses were visited and their employees investigated for six months. This hypothesis was reinforced by Queen Victoria herself, for whom the culprit must have been a butcher or cattle dealer from one of the cattle ships that operated between London and Continental Europe, taking into account the proximity of Whitechapel to the London docks and the docking of these ships every Thursday or Friday, and their departure on Saturday or Sunday, which coincided with the days on which the deaths had occurred. Despite the above, the fact that none of the murders occurred on any of the arrival dates of the ships led the police to dismiss this conjecture.

Suspicions

Given the paucity of forensic evidence and the various contradictions in contemporary sources on the case, it is almost impossible to establish the identity of Jack the Ripper. Although DNA tests have been carried out on letters attributed to the murderer, the results were inconclusive and are now too corrupted to provide any useful information.1 However, there are several theories about Jack the Ripper's identity. One of the most widespread theories at the time was that the killer must have lived in Whitechapel and had a steady job, as the crimes occurred on weekends close to public holidays, and in streets close to each other. It was also thought that the perpetrator might be an educated, upper-class man, possibly a doctor or aristocrat, who had come to the neighbourhood from a more affluent background, although such assumptions may have been due to cultural stereotypes such as fear of doctors, distrust of science, or exploitation of the poor by the rich.

In the years following the murders, records indicate that the police were suspicious of anyone remotely linked to the case, as well as several celebrities who had not even been investigated in the original enquiry. With the passage of time, and the death of those who lived at the time, contemporary authors have been at ease to accuse anyone "without the need for historical evidence". Although a memorandum by Meville Macnaghten in 1894 contained the names of three suspects referred to in police records at the time, the fact remains that the evidence against them was merely circumstantial and therefore they were not prosecuted. In all, there were over a hundred Ripper suspects, including Montague Druitt, Severin Klosowski, Aaron Kosminski and Francis Tumblety; others, however, were linked only by the press, such as William Bury, Thomas Neill Cream, Robert D'Onston Stephenson and Frederick Deeming.

Letters

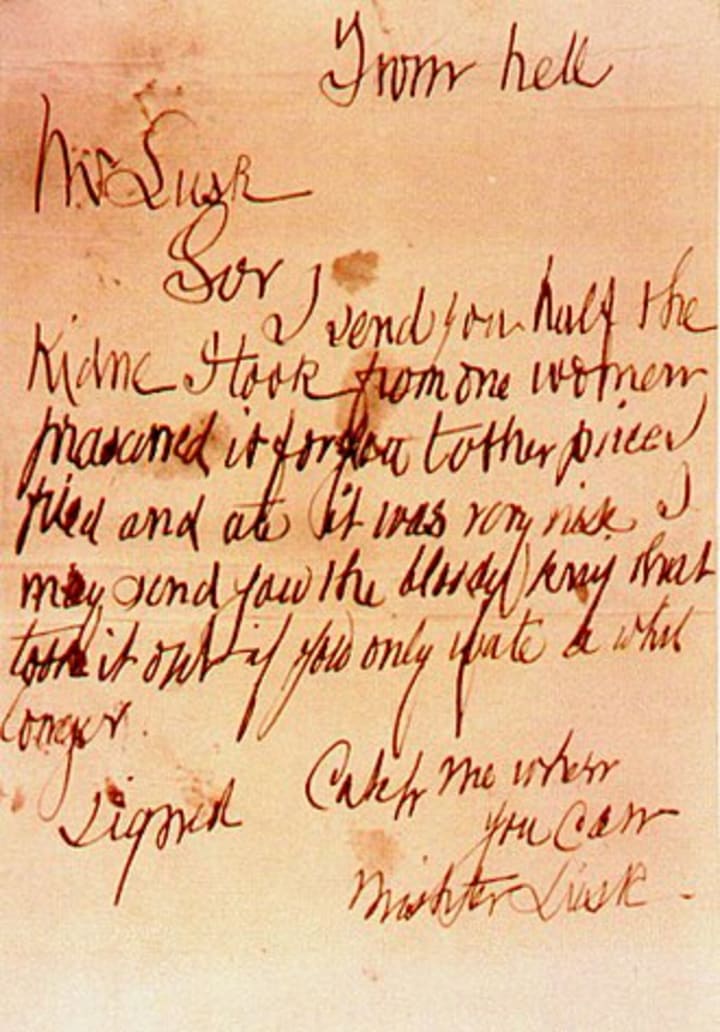

The press and police received numerous letters in the course of the Whitechapel murders, and while some were proposals to help catch the killer, most were of no use to the investigation. However, hundreds of these letters were allegedly from the Ripper, and three of them were notable: the "Dear Boss" letter, the "Saucy Jacky" postcard and the "From Hell" letter.

The "Dear Chief" letter was dated 25 September 1888 and was initially received by the Central News Agency on 27 September, which coincided with the postmark. The news outlet forwarded the document to Scotland Yard two days later. Initially considered a hoax, the document gained notoriety after the discovery of Eddowes' body, as the body was missing an ear and the letter, sent three days before the murder, included a threat to "cut off the lady's ears". Despite this, the investigations concluded that Eddowes' ear had been incidentally cut off by the killer during his attack. In addition, the document also stated that the perpetrator was to send his victim's ears to the police, which did not happen. The significance of this letter also lies in the fact that its author first used the nickname "Jack the Ripper" to refer to himself, and since then the press and police, who used to call him "Leather Apron", began to refer to him as such. Some sources pointed out that the nickname had actually been used originally in a letter dated 17 September of the same year, however there was no consensus in validating this assumption and it was considered a hoax in 20th century police records.

Similarly, the Central News Agency received the postcard "Saucy Jacky" on 1 October, the date of the postmark. It should be noted that the handwriting and tone were similar to those of the "Dear Boss" letter, with the author claiming that two more victims had been killed in close proximity to each other, and describing the murder as "a double event", presumably in reference to the deaths of Stride and Eddowes. Although the letter was thought to have been sent before the murders were made public by the police, so that it would have been unlikely that anyone else would have known about the double event at the time, the postmark date indicated that the author had sent the document more than 24 hours after the deaths, when the media was already giving the public coverage of what had happened.

George Lusk, leader of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, received the letter "From Hell" on 16 October. However, when compared to previous letters, the document had a different handwriting and style of writing. The letter came in a small box that also contained half of a kidney preserved in ethanol, and the author claimed to have eaten the rest of the fried organ. Although some sources deduced that the kidney belonged to Eddowes, whose corpse lacked the organ, other references concluded that it was only a macabre joke. The English surgeon Thomas Openshaw, of the London Hospital, examined the kidney and determined that it was indeed human and came from the victim's left side. However, he was unable to establish any other biological characteristic. Later the doctor received another letter signed by the Ripper.

Scotland Yard published facsimiles of the "Dear Chief" letter and the postcard on 3 October in the hope that someone would recognise the handwriting. In Warren's opinion: "I think this is all a hoax, but we are obliged in any case to find the author. On 7 October, George R. Sims explained in the Sunday paper Referee that the letter had been written by a journalist to boost the popularity of a newspaper. Based on this hypothesis, the police confirmed shortly afterwards that they had identified a journalist named Tom Bullen as the author of the letters, according to a letter sent by Inspector John Littlechild to George R. Sims on 23 September 1913. It was not until 1931 that the journalist Fred Best confessed that he and a colleague from The Star had written the letters signed by Jack the Ripper in order to increase interest in the Whitechapel murders and "keep the business alive".

The media

Although Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer, his crimes received unprecedented media coverage thanks to tax reforms passed in the 1850s that encouraged the mass distribution of low-priced newspapers. During the Victorian era, such publications boomed, including newspapers as cheap as a halfpenny and popular magazines such as the Illustrated Police News, which focused their efforts on publicising the murderer.

Journalists were aware that there was little information they could publish about the Whitechapel crimes, as the Manchester Guardian acknowledged, noting that "any information that may be in the possession of the police appears to need to be kept secret.... It is believed that their attention is particularly directed at.... a notorious character known as 'Leather Apron'". The sense of frustration in certain media about the few details that were known about the police investigations led to publications that lacked veracity, and fictitious descriptions of the killer emerged, although some reporters occasionally dismissed the false rumours as "the result of the journalist's mythical fanciful excrescence". As these erratic stories spread, some began to make conjectures based on press claims; for example, the police arrested John Pizer, a Jewish leather shoe salesman who was known by the nickname "Leather Apron", the same nickname used by the Manchester Guardian to refer to the Ripper. Once it was confirmed that there was no evidence linking him to the crimes, Pizer was released

About the Creator

diego michel

I am a writer and I love writing

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.