What DHS Secretary Kristi Noem said vs. what the videos show

Governing law & policy: deadly force and moving vehicles Constitutional standards (Supreme Court)

NBC News and PBS recapped the competinBelow is a structured, evidence-backed analysis of the Minneapolis ICE shooting and the claims made by DHS Secretary Kristi Noem—including the applicable federal laws/policies and how intent vs. recklessness factor into a potential case. I’ll keep this clear, precise, and grounded in the video evidence and governing law.

1) What DHS Secretary Kristi Noem said vs. what the videos show

Noem’s public statements (January 7–12, 2026):

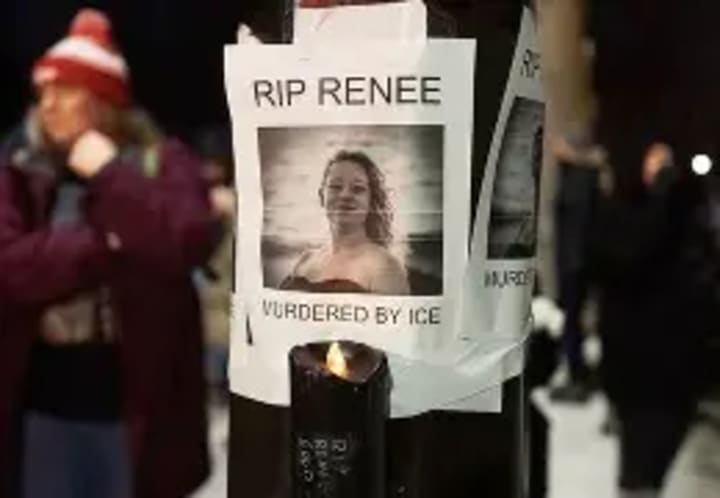

Noem repeatedly asserted that the woman (identified as Renee Nicole Good, 37) "attempted to run ICE officers over,” describing the event as an “act of domestic terrorism” and claiming the agent “followed his training” and acted in self-defense. She also said the officer was hit by the vehicle and later treated at a hospital.

DHS/DOJ Use‑of‑Force Policy (failure to avoid positions with no alternative, firing at moving vehicle operator only if deadly force is otherwise justified, consider bystander hazards, not solely to stop escape)

What multi-angle videos and independent analyses show:

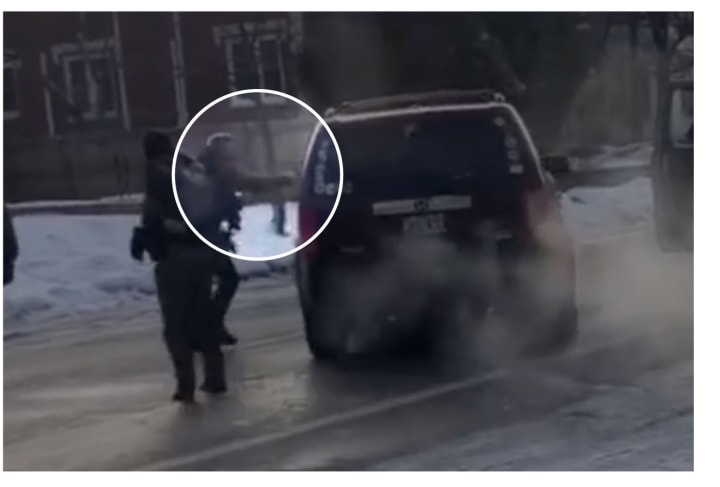

Multiple recordings show Good’s SUV was perpendicular and stopped in the street for minutes before agents approached. When officers arrived, they loudly ordered her to exit; one pulled on her driver-side door while another moved to the front of the vehicle. The SUV briefly reversed and then began moving forward while turning right away from the agent at the moment shots were fired. The firing officer first shot through the windshield, then two more shots through the open driver’s window as he moved out of the front path. The car then accelerated and crashed into a parked car and a pole.

USA TODAY’s frame-by-frame analysis and ABC’s minute-by-minute timeline both indicate the vehicle’s wheels were turned right, away from the firing officer at the instant he fired; shots continued after the officer had moved out of the vehicle’s immediate path.

Local officials (Mayor Jacob Frey, Gov. Tim Walz) publicly disputed DHS’s self‑defense narrative, calling it “garbage” and stating the videos show the driver trying to leave, not attack.

g narratives and highlighted that FBI is leading the investigation while DHS continued to frame the incident as self‑defense.

Bottom line: Noem’s claim of a clear intent to run over and kill officers is not corroborated by the released videos and independent analyses, which show a more nuanced scene where the **car was turning away as shots were fired and the officer wasn’t in the immediate path for the final shots. Whether contact occurred just before the first shot is disputed across angles, but the continued shots after the officer cleared the front weigh against the narrative of a persistent imminent lethal threat.

2) Governing law & policy: deadly force and moving vehicles

Constitutional standards (Supreme Court)

Tennessee v. Garner (1985): Deadly force against a fleeing suspect is allowed only if the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury and deadly force is necessary to prevent escape. **Shooting solely to stop escape violates the Fourth Amendment.

Graham v. Connor (1989): All use‑of‑force claims are judged by “objective reasonableness”—what a reasonable officer would do in the moment, considering severity, immediacy of threat, and resistance/fleeing. Motivation.

As the car starts to move forward, the officer begins stepping aside while drawing his pistol.

is irrelevant; facts and circumstances control.

DHS / DOJ use‑of‑force policy (moving vehicles)

DHS policy (updated 2023): Deadly force only when necessary and when the officer reasonably believes there’s an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury; not solely to prevent escape. Officers should avoid placing themselves where deadly force becomes the only option. Discharging at operators of moving vehicles is prohibited unless deadly force is otherwise justified, and officers must consider hazards to bystanders from an out‑of‑control vehicle.

DOJ policy (updated 2022): Officers may use deadly force only when no reasonably effective, safe, feasible alternative exists. Firearms may not be discharged solely to disable a moving vehicle; if a vehicle is the threat, moving out of the vehicle’s path is a recognized alternative when feasible.

News explainer round‑ups and AP coverage reinforce that most agencies restrict firing at moving vehicles unless there’s an **immediate lethal threat and no safer alternative.

After the officer fires his first shot, he can be seen standing on the car’s left side.

ICE’s directive page was temporarily redacted after the shooting; coverage and prior versions show substantively similar restrictions, consistent with DHS.

Policy take‑away: If the vehicle was turning away and the officer had cleared the front, the continuation of gunfire (two shots through the driver window appears in tension with DHS/DOJ standards requiring an imminent lethal threat and the absence of reasonable alternativesles.

3) Federal laws the driver could have been charged under (if alive) — and the officer could face

Potential charges against the driver (as asserted by DHS, subject to proof)

18 U.S.C. § 111 (Assaulting/resisting federal officers): If a driver intentionally uses force or a vehicle as a dangerous weapon against an officer, penalties can reach 20 years when a dangerous weapon is used or bodily injury results. But this requires proof of intent and contact/actual threat at the moment of force. law.cornell.edu

DHS Secretary Kristi Noem said Good “attacked” officers and tried to ram them after they got stuck in snow.

18 U.S.C. § 1114 (Attempted murder of a federal officer): Requires attempt to kill a federal officer performing official duties; prosecutors must prove intent to kill (not merely recklessness).

Relevance here: The evidence is contested—some angles suggest possible contact just before the first shot, while others show the agent moving away and wheels turned right. Intent to kill is a high bar, and the totality (minutes of stationary positioning, turning away at the moment of gunfire) raises reasonable doubt about specific intent vs. recklessness or confusion.

Potential federal exposure for the officer

18 U.S.C. § 242 (Deprivation of rights under color of law): Criminal civil‑rights statute used when an officer willfully uses excessive force violating the Fourth Amendment. Penalties escalate if dangerous weapon is used or if death results—up to life. Requires proof the officer’s use of force was objectively unreasonable and that he willfully acted in color of-law)

How § 242 could apply: If investigators conclude the agent fired without an imminent threat and contrary to DHS/DOJ policy and constitutional limits (Garner/Graham), the conduct may meet excessive force under the Fourth Amendment, opening a pathway to § 242. Whether the required willfulness can be proved is a fact-intensive question. supreme.justia.com (https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/490/386/),

Administrative/policy violations: Even if criminal charges aren’t pursued, the shots through the windshield and driver window while the officer was not in the immediate path may violate DHS/DOJ policy (moving vehicles, imminent threat, reasonable alternatives), supporting *administrative discipline, civil litigation (e.g., Bivens/FTCA), or § 1983‑style constitutional claims via federal analogs.

Renee Nicole Good, ODU Alum, Murdered in Minneapolis ICE Enforcement .

4) Intent vs. recklessness — why it matters here

Intent means the actor’s conscious objective is to cause a specific result (e.g., to kill or to strike the officer with the vehicle). It’s required for attempted murder under § 1114. [\[law.cornell.edu\]](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/1114)

Recklessness means the actor consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk; it can support assault or manslaughter‑type theories, but not attempted murder. In use‑of‑force reviews, reckless tactics by officers (e.g., stepping in front of vehicles, escalating rather than de‑escalating) can undercut self‑defense claims and violate policy even if no criminal intent is found.

Applied here: The videos show non‑uniformed filming, door‑pulling, and the officer firing while also holding a cell phone, which some coverage notes; these facts can color the reasonableness analysis. If the vehicle was turning away and the officer had cleared danger, continued shots look less like response to imminent lethal threat and more like reckless escalation—potentially violating Garner/Graham and policy.

5) Was Noem “lying”? A careful, factual framing

It’s accurate that Noem publicly claimed Good“attempted to run them over … to kill them”and called it “domestic terrorism,”before full investigative findings were released.

It’s also accurate that independent video analyses contradict the simplicity of her claim, showing the car turning away and shots fired when the officer had moved out of immediate danger, which undermines a categorical assertion of clear, ongoing intent to kill.

Conclusion: Whether to label her statements a “lie” depends on knowledge and intent. What we can say confidently is that her definitive characterization is not supported by the available video record, which shows a more ambiguous and policy‑sensitive situation—one that **raises serious questions under DHS/DOJ standards and Fourth Amendment case law.

18 U.S.C. § 1114 (attempted murder of federal officer—requires intent to kill law.

18 U.S.C. § 242 (willful deprivation of rights under color of law if excessive force proved; death‑result enhancement) [\[law.cornell.edu\]](https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/242)

DHS/DOJ Use‑of‑Force Policy (failure to avoid positions with no alternative, firing at moving vehicle operator only if deadly force is otherwise justified, consider bystander hazards, not solely to stop escape)

Rip in peace Renee Nicole Good

7) What happens next

The FBI leads the criminal investigation; outcomes can include no charges, federal civil‑rights charges under § 242, administrative discipline, or civil suits. Public briefings indicate deep disagreement between federal and local officials; additional body‑worn or cellphone footage and forensic data will be decisive.

About the Creator

Organic Products

I was born and raised in Chicago but lived all over the Midwest. I am health, safety, and Environmental personnel at the shipyard. Please subscribe to my page and support me and share my stories to the world. Thank you for your time!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.