Inside the Mind of Bryan Kohberger: What His Research Papers Reveal

How Bryan Kohberger’s academic writings on crime, justice, and emotion offer a disturbing glimpse into the mind of the accused Idaho killer.

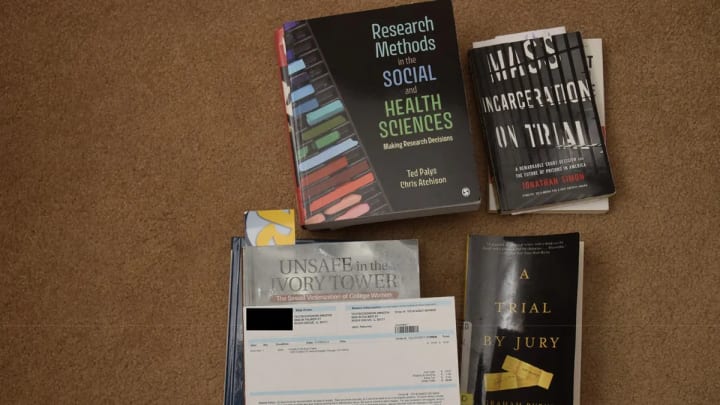

When investigators entered Bryan Kohberger’s apartment near Washington State University after his arrest, they didn’t just find the usual evidence police seek out in a homicide case—clothing, electronics, or DNA swabs. They also cataloged something far stranger: stacks of research papers, quizzes, and essays from his criminology PhD program.

The Idaho State Police photographed these documents and included them in the latest round of discovery files. What might otherwise be dismissed as routine coursework has taken on a haunting new significance in hindsight. Each essay, each handwritten note, seems to offer an unnerving glimpse into the inner workings of Kohberger’s mind before the murders at 1122 King Road.

The writings reveal more than academic curiosity. They expose the obsessions of a man who studied crime not simply to understand it, but perhaps to manipulate the system around it. What emerges is a disturbing portrait of someone who believed his knowledge of criminology might shield him from the consequences of his own alleged actions.

Rational Choice vs. Emotion in Crime

One of the recurring themes in Kohberger’s papers is the debate between rational choice theory and emotional decision-making. Rational choice theory, a cornerstone in criminology, argues that offenders weigh risks against rewards before committing crimes. The “cost-benefit analysis” of crime suggests that criminals act logically, much like economists making calculations.

Kohberger’s work, however, challenges that neat formula. He often wrote about how emotions can override rationality. In one paper, he noted that crimes of passion or crimes driven by adrenaline cannot be fully explained by logic. Intense emotional arousal, he argued, “confounds notions of extremely cold criminal calculus.”

In hindsight, this strikes a chilling chord. Experts have suggested that while Kohberger may have planned the Moscow murders with meticulous detail, his actions once inside the house likely spiraled into chaos. He may have entered with one plan—possibly targeting a single victim—but adrenaline, fear, and rage may have driven him to kill four people instead.

It’s eerie to see him put these theories on paper before the fact. The very mistakes investigators now say he made—leaving behind DNA, parking carelessly, being spotted by a roommate—align with his own writing that offenders often lose control once emotions take over.

Studying Police Weaknesses

Another paper stood out for its focus on law enforcement itself. Kohberger proposed a study of local police officers and their training in digital forensics. He noted that small-town police departments often lacked specialized knowledge in areas like cybercrime or advanced forensic analysis.

On paper, this was just a research proposal. In hindsight, it feels almost predatory. Kohberger chose to live just across the border from Moscow, Idaho—a town with a small police force unaccustomed to handling high-profile homicide investigations. Was this coincidence, or did his academic research inform his sense of security in targeting victims there?

The Moscow Police Department, with fewer than 40 officers, had never investigated a quadruple homicide before. Within weeks, state police and the FBI were called in. Reading Kohberger’s work now, one can’t help but wonder: did he believe the gaps he studied in class could protect him in real life?

The System on Trial: Wrongful Convictions

Several of Kohberger’s assignments focused on the flaws of the justice system. He cited statistics showing that between 2% and 8% of all convictions may be wrongful. He wrote extensively about false confessions, eyewitness misidentifications, and the misuse of forensic testimony.

In one quiz, he pointed out that 70% of wrongful murder and rape convictions involved faulty eyewitness identifications, 30% involved false confessions, and nearly half included misleading testimony from forensic experts. He also highlighted how these errors disproportionately affected people of color.

This wasn’t just theoretical knowledge. Observers in court often speculated that Kohberger whispered legal strategy to his attorney, Anne Taylor. His essays show he knew precisely where the cracks in the system lay—memory flaws, procedural errors, and the limits of forensic certainty.

If he truly believed he could manipulate these weaknesses, it may explain his calm demeanor during hearings. To him, court may have felt less like a reckoning and more like a seminar where he could critique the process.

Sexual Offending and Emotional Arousal

Among the most disturbing writings were those focused on sexual predators. Kohberger described how offenders often enter situations with one intent but are overtaken by irrational motives and emotional arousal. He analyzed how weapon use increased compliance and arousal, even though it carried long-term risks.

In one paper, he noted that “suboptimal decisions are reflected in the data” because offenders, blinded by immediate outcomes, lose sight of consequences. He even ventured into controversial territory, writing about fetishes and paraphilias, lumping behaviors like voyeurism and exhibitionism alongside discussions of transvestism and fetishism.

Reading these passages now is deeply unsettling. Prosecutors have said there was no evidence of sexual assault at the King Road house. But Kohberger’s writings raise the possibility that a sexual component doesn’t always manifest in physical acts—it can exist in the thrill, the control, the arousal of the crime itself.

The parallels between his academic analysis and the crimes he’s accused of are hard to ignore.

Death Penalty: Contradictions and Strategy

Kohberger also wrote extensively against the death penalty. He argued that capital punishment was racially biased, ineffective as a deterrent, and harmful as public policy. He cited statistics showing disproportionate application against Black defendants and argued that harsher sanctions do not reduce crime rates.

Yet classmates remembered him arguing the opposite in discussions, pushing pro-death penalty arguments in conversations. Was this contradiction evidence of genuine ambivalence—or simply a sign that he wrote whatever would get him the best grade?

Had the case gone to trial, his anti-death penalty essays would almost certainly have been used during the mitigation phase. His own words might have become exhibits in a fight to spare his life. That possibility underscores how much his academic world and his criminal case intertwined.

Grades, Ego, and Arrogance

For all his intellect, Kohberger was far from a flawless student. Professors frequently critiqued his writing for being overwrought, filled with “flowery language” and an excessive use of passive voice. He often seemed more interested in sounding smart than communicating clearly.

He usually scored in the 90s, but not always. On one paper about the death penalty, he received an 80—his lowest mark in the materials reviewed. The feedback stung: he had jumped into analysis without adequately summarizing the book assigned.

It’s easy to imagine that such criticism frustrated him. For a PhD candidate, an 80 is far from stellar. His need to appear intellectually superior may have mirrored the arrogance he displayed later in court, sitting stone-faced as victims’ families described their pain.

Inside the Courtroom: Blank Face or Analytical Mind?

Courtroom observers frequently remarked on Kohberger’s blank expression. As grieving families poured out their anguish, he rarely flinched. At most, an eyelid twitched. To many, this looked like indifference.

But revisiting his academic writings, another possibility emerges. Perhaps he wasn’t indifferent—perhaps he was analyzing. Just as he dissected legal procedures in his essays, he may have been cataloging courtroom dynamics like a student in a seminar.

His knowledge of wrongful convictions, prosecutorial misconduct, and faulty eyewitnesses suggests he may have seen himself not as a passive defendant but as a participant in the legal chess match. Whether this confidence was justified or delusional is another matter.

The Bigger Picture: When Criminology Crosses the Line

There’s a long-standing fascination with criminology students who cross the line from studying offenders to becoming offenders themselves. Most never do—but Kohberger’s case raises questions about what happens when academic obsession turns dark.

In his papers, he wasn’t just learning about the justice system. He was identifying its weaknesses, theorizing about emotional breakdowns during crimes, and critiquing police shortcomings. He wasn’t just writing essays—he was rehearsing scenarios.

That rehearsal may have fed a dangerous illusion: that his knowledge made him untouchable. But in the end, the very flaws he studied weren’t enough to save him. DNA, cell phone records, and surveillance cameras anchored the case against him in ways no amount of theory could undo.

Conclusion: Lessons From the Papers

Bryan Kohberger’s essays and quizzes were meant to earn grades, not headlines. Yet they now stand as eerie artifacts—academic work transformed into psychological evidence. They reveal a man fascinated by crime’s emotional volatility, by law enforcement’s limitations, by the system’s failures.

But they also reveal arrogance. He believed he could outthink, outplan, and outmaneuver the very system he critiqued. Instead, his papers serve as haunting reminders that knowledge does not equal wisdom—and that studying crime is a far cry from escaping its consequences.

In the end, the writings tell us as much about his delusions as his education. They are less a map of how to get away with murder than a trail of breadcrumbs showing why he never could.

About the Creator

Lawrence Lease

Alaska born and bred, Washington DC is my home. I'm also a freelance writer. Love politics and history.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.