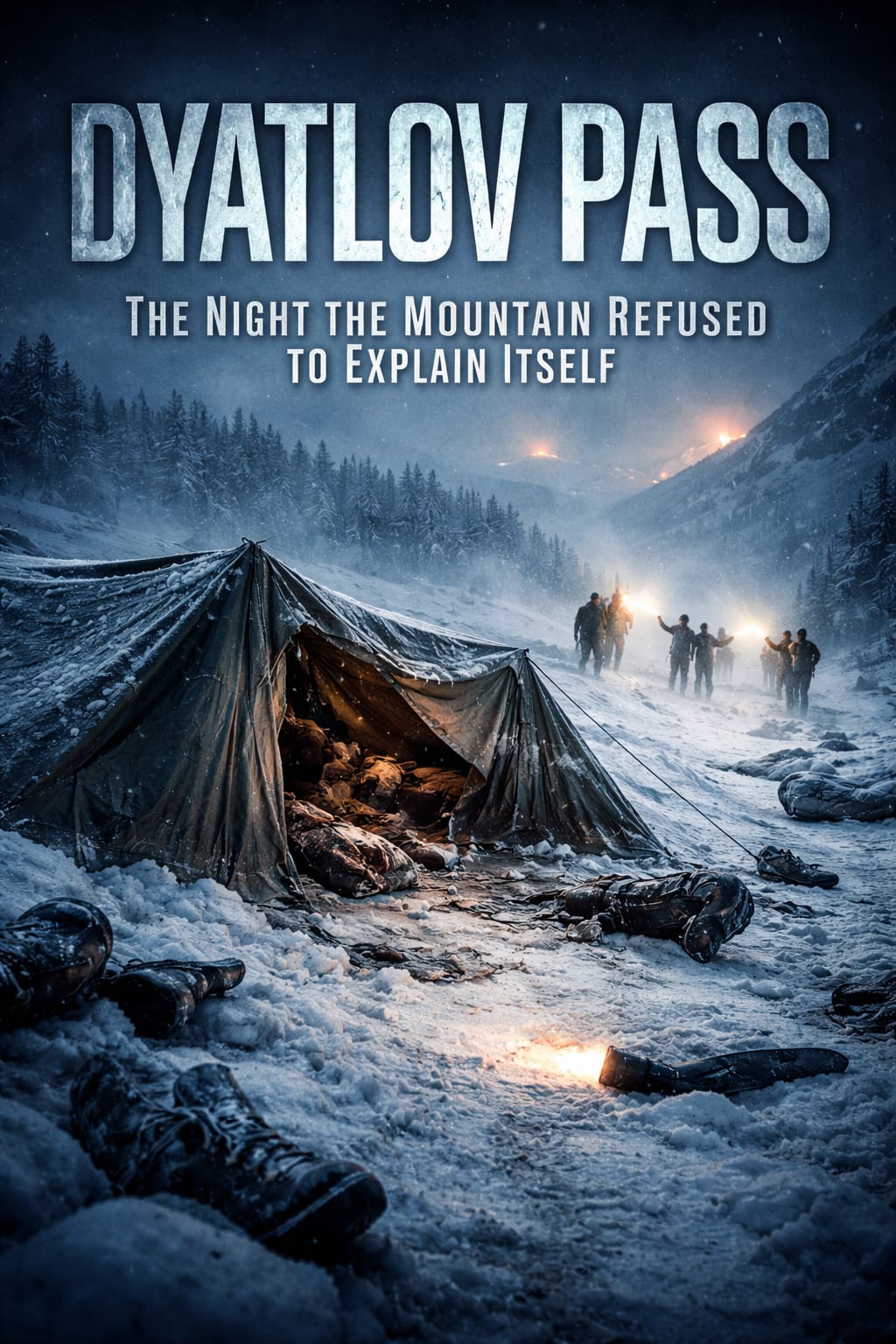

Dyatlov Pass

The Night the Mountain Refused to Explain Itself

The northern Ural Mountains are not dramatic in the way the Alps are dramatic. They do not rise like stone cathedrals or glitter with postcard beauty. They are older than that—rounded, wind-carved, patient. In winter, they become something else entirely: a vast white emptiness where sound dies quickly and mistakes are punished without mercy.

In late January of 1959, nine young people set out into that emptiness.

They were students and recent graduates from the Ural Polytechnic Institute, most of them in their early twenties. They skied together, trained together, trusted one another. Their leader, Igor Dyatlov, was 23 years old—serious, meticulous, known for careful planning and quiet competence. This was not a reckless group chasing adventure for the thrill of it. This was a disciplined expedition aiming to complete a Category III winter trek, the highest difficulty rating at the time.

They packed well. They documented everything. They kept diaries, took photographs, joked in their notes. Nothing in their writing suggests fear, tension, or even unease.

That is what makes what happened next so disturbing.

Their last confirmed campsite was on the eastern slope of a mountain the local Mansi people called Kholat Syakhl—often translated as “Dead Mountain.” The name predates the incident by centuries and refers not to curses, but to the fact that game animals rarely passed through the area. It was an empty place.

On the night of February 1st, 1959, the weather was harsh but not unusual for the region: strong winds, sub-zero temperatures, blowing snow. The group pitched their tent on an exposed slope instead of descending into the forest below. Investigators later speculated that Dyatlov may have done this deliberately, as a training exercise—to practice camping under worst-case conditions.

If so, it would be his final decision.

Days passed. Then weeks. When the group failed to return or send word, a search was organized—first by fellow students, then by the military. On February 26th, rescuers found the tent.

It was still standing.

That detail alone should have been comforting. It wasn’t collapsed. It hadn’t been flattened by an avalanche. But as the searchers drew closer, comfort turned into confusion.

The tent had been cut open from the inside.

Not the entrance. The side.

Clothing, boots, food, and equipment were still inside—neatly arranged, as if the occupants had planned to return. Footprints led away from the tent in a scattered line down the slope. Some were barefoot. Some wore socks. A few had a single boot.

No signs of a struggle. No animal tracks. No indication of panic in the snow itself—just a quiet, impossible retreat into the freezing dark.

The first two bodies were found beneath a large cedar tree about a mile from the campsite. They were nearly naked, dressed only in underwear. Their hands were raw and damaged, as if they had clawed at bark. A small fire had been built beneath the tree, its remains barely visible.

They had died of hypothermia.

Between the tree and the tent, searchers found three more bodies, spaced out along the slope as if they were trying—desperately—to return. One was Dyatlov himself. All showed signs of extreme cold exposure. No fatal injuries.

At this point, the story might have ended as a tragic but explainable case: disorientation, exposure, a poor decision under stress.

But four members of the group were still missing.

Their bodies were discovered months later, buried under several meters of snow in a ravine. And this is where the case breaks apart.

These four were better dressed, wearing clothes taken from their already-dead companions—suggesting they survived longer. But their injuries were catastrophic.

One woman had a fractured skull. Another had multiple broken ribs. One man’s chest injuries were so severe that a medical examiner compared the force to that of a car crash.

And yet—there were no external wounds consistent with such trauma. No bruising, no lacerations, no signs of impact against rocks or trees.

One woman was missing her tongue.

Another had radiation traces on parts of his clothing.

The official Soviet investigation concluded in May 1959 with a single, vague sentence:

“The cause of death was a compelling natural force which the hikers were unable to overcome.”

The case was closed.

That sentence has haunted people ever since.

Over the decades, theories multiplied.

Some argued avalanche—but the tent was not buried, the slope angle was shallow, and experienced skiers would not flee half-dressed from a minor slide. Others proposed katabatic winds, sudden violent gusts capable of producing terrifying noise and pressure. This might explain panic, but not the injuries.

There were whispers of military tests, secret weapons, or parachute mines detonating in the air. Witnesses reported strange orange lights in the sky that night. Files were classified. Some remain missing.

Others blamed infrasound, low-frequency sound waves produced by wind interacting with the mountain’s shape, possibly inducing panic or dread. Interesting—but still speculative.

Then there are the wilder ideas: escaped prisoners, local tribes, unknown creatures

About the Creator

The Insight Ledger

Writing about what moves us, breaks us, and makes us human — psychology, love, fear, and the endless maze of thought.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.