The Zurich Cipher

Chapter 7 : The Warsaw Conundrum

May 1937 – Warsaw

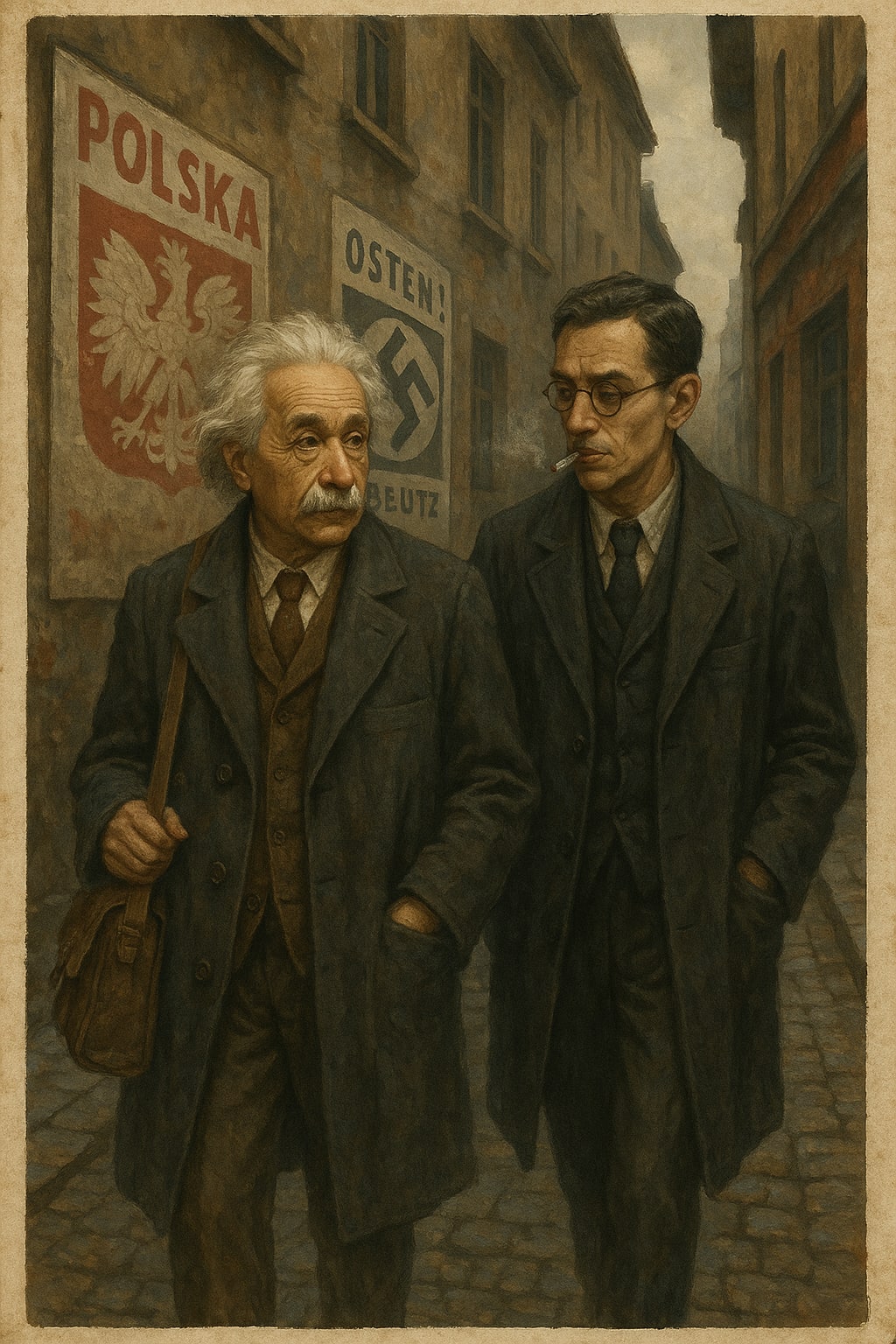

The Polish air was crisp, bitter even in May, as Albert Einstein stepped off the overnight train from Prague. He wore the same worn wool coat, the same leather satchel heavy with annotated drafts and diagrams — though now its contents were more dangerous than ever: not formulas, but agreements, whispers, and warnings. Warsaw was no longer just a city on the map of occupied minds — it had become a strategic battleground in the clandestine war of ideas.

Waiting on the platform was a man of similar intellect but different battle scars — Stefan Banach, the mathematical prodigy of Lwów. Gaunt, fast-talking, and chain-smoking, Banach had agreed — reluctantly — to serve as a liaison between the Polish scientific underground and Einstein’s “Central Committee of European Rationalists.” The group had no formal name, but in Gestapo reports, they were already known as der Denkkreis: the Circle of Thought.

“Come,” Banach said without a handshake. “There are ears even in the bricks.”

They walked silently through Śródmieście, past the poster-plastered walls that alternated between Polish state propaganda and veiled threats from the German embassy. They ducked into a bookshop posing as a lending library, where the books on the front shelf were all decoys — Tolstoy, Mickiewicz, Goethe — hollowed out and coded. Behind a locked door, in a dim back room lit by a kerosene lamp, sat five people, none older than thirty. A physicist, a linguist, a rabbi, a medical student, and a communist printer.

Einstein removed his coat and sat in silence. They watched him the way acolytes might a prophet — if the prophet came with footnotes.

“It is not science we lack,” said the physicist, whose name was Emilia Kowalska, “but belief that science can still protect us.”

Einstein replied softly, “That is precisely why it must.”

The meeting stretched for hours. The group discussed the tightening grip of German influence in the Polish press, the slow erosion of intellectual freedoms, the growing suspicion toward Jewish professors in Warsaw University. Einstein listened more than he spoke, but when he did, it was precise:

“Authoritarianism fears not guns, but minds that will not align. You are dangerous not because you resist physically — but because you still think freely.”

Banach scrawled equations on a chalkboard in the corner, building a cipher to allow encrypted letters between Warsaw and Zurich. Meanwhile, Einstein outlined a new plan — one Banach at first dismissed as “impossible in this climate” — to create a mobile academic journal, printed from movable locations, translated into four languages, and smuggled across borders disguised as medical manuals.

“It will be called Ratio Libera,” Einstein declared. “The Free Reason.”

Emilia raised an eyebrow. “And who will publish it? The Polish Ministry of Health?”

Einstein smiled. “A Catholic hospital in Gdańsk has already agreed. Their chief surgeon studied under my cousin.”

As the night deepened, they passed around hard bread and black tea. Einstein spoke with the young rabbi, who quoted Spinoza in whispered tones. They discussed theology, resistance, and the nature of moral courage.

Before dawn, Banach walked Einstein back to the train station. The sky had begun to bruise with light.

“You’ll be followed, you know,” Banach muttered. “If not now, soon.”

Einstein nodded. “Let them follow thoughts — they may yet learn from them.”

Banach paused at the edge of the platform. “Do you ever regret it? Not leaving for America?”

Einstein looked east, toward the rising sun.

“Sometimes,” he admitted. “But then I remember: no revolution is born from safety.”

The train doors closed with a hiss.

Back in the bookshop, Emilia pulled a small bundle from under a floorboard. It was a single galley proof, typeset and thin — the first issue of Ratio Libera. At the bottom, beneath a quote from Galileo, was a signature in blue ink:

A. Einstein, Editor-at-Large.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.