The Copenhagen Accord

Chapter 8 : Silent Strategies

May 2, 1936 – Copenhagen

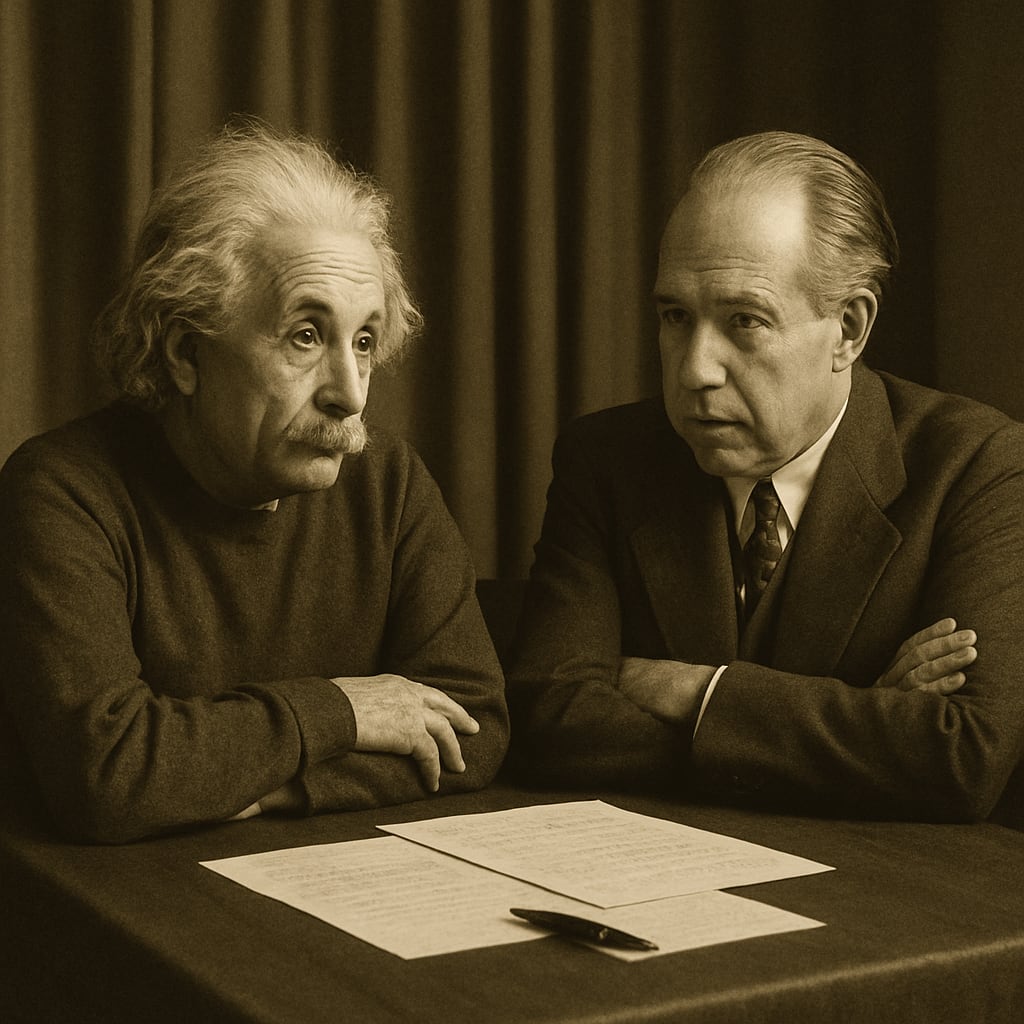

The morning sky over Copenhagen was washed in grey. Einstein sat in the small breakfast room of Niels Bohr’s modest home, stirring his tea with the absentmindedness of a man whose thoughts danced between atoms and the future of civilization.

Bohr had summoned him urgently. There were whispers of a secret agreement circulating between certain neutral Scandinavian nations—a pact for scientific cooperation independent of both Berlin’s pressures and Moscow’s shadows. It was the sort of idea that once would have seemed merely academic. Now, it could shape the fate of Europe.

Across the table, Bohr looked older, his eyes sunken from sleepless nights. “Albert,” he said quietly, “there are more than just physicists in this house today.”

Einstein raised an eyebrow. “Spies?”

“Statesmen,” Bohr corrected. “And yes, perhaps one or two of the other kind as well.”

They had both come to understand that science could no longer exist in a vacuum. The Nazis had accelerated their research into uranium. Einstein had read enough of the coded letters exchanged between former students to realize what was at stake. Germany was building something—something far beyond the reach of conventional warfare.

That afternoon, the meetings began. In a quiet university chamber cloaked in thick velvet drapes, Einstein stood beside Bohr, translating equations into arguments. The Scandinavian delegation—primarily Danish and Swedish—listened with the solemnity of men unaccustomed to wielding power yet burdened now with the need to act.

“We do not ask you to choose a side in war,” Einstein said, his accent pronounced but his voice calm. “We ask you to choose a side in truth.”

A hush followed his words. One of the Swedish ministers, Henrik Nyström, spoke next. “And if we align ourselves with you, Herr Einstein, will it not paint a target on our backs?”

Bohr intervened. “The target already exists. It is written on every textbook your students read. Knowledge is now a battlefield.”

The ministers glanced at one another. They had come expecting philosophy. Instead, they were being asked for resistance.

What emerged that night was the seed of what would later be called the Copenhagen Accord—a clandestine network of neutral laboratories and safe havens for exiled scientists, linked through encrypted channels and funded by private donors. It was Bohr’s idea to include not only physicists but chemists, medical researchers, and mathematicians. “Truth,” he said, “needs allies in every language.”

Einstein, exhausted but invigorated, agreed to stay on for another week. Together, he and Bohr mapped out the first routes—paths by which persecuted minds could escape, and discoveries could continue unmolested.

In a moment of quiet reflection, Einstein asked his old friend, “Do you believe it will be enough?”

Bohr sipped his coffee and looked out the window. “It must be.”

The next day, Einstein received a coded message from Prague. It contained only a single line: “The Eagle seeks iron.” He knew what it meant. Germany had begun testing radioactive isotopes near the Polish border.

It would be months before the Allies would even hear rumors. But here, in Copenhagen, beneath the shadows of ancient steeples and snow-touched rooftops, a counter-effort had begun—not of weapons, but of minds.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.