The Quiet Revolution

Chapter 9: Echoes of the Atom

May 1943 — Geneva

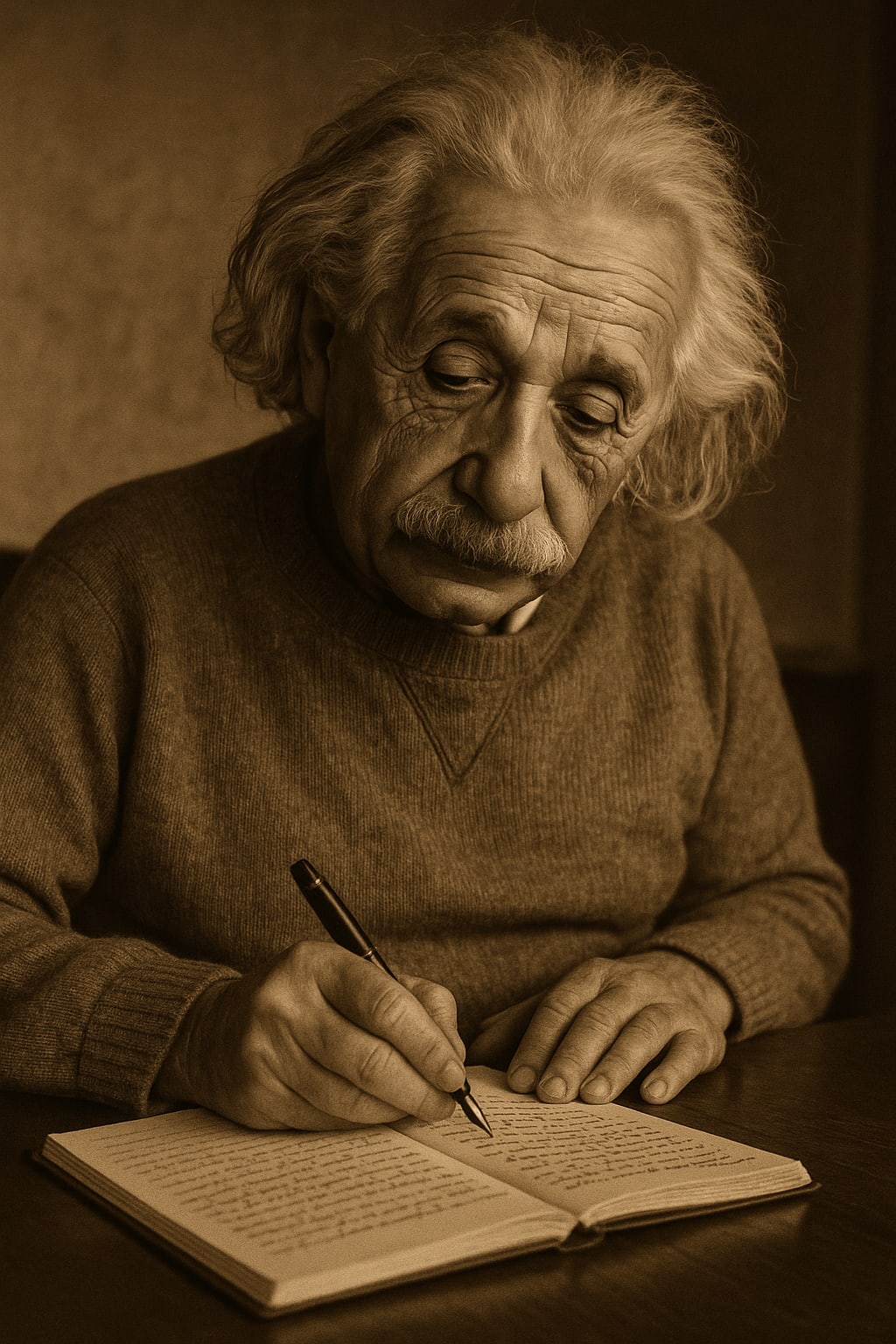

I write tonight with a heavy hand and a restless heart.

The war has swallowed much of Europe, yet Switzerland—like a rock in a torrent—remains outwardly calm. Behind the diplomatic neutrality, though, I feel the pressure mounting, not only on my nation, but within me. The work we began to stop the atomic catastrophe before it starts has taken a darker turn.

Earlier this year, I received news that the Germans are indeed accelerating their nuclear program. Heisenberg, whom I once taught and respected, is rumored to be leading a team under direct orders from the Reich. I fear that our warnings and peaceful appeals have not reached him. Worse still, some Swiss officials—out of either fear or self-interest—have begun discussions with both sides, hoping to profit or survive no matter the war’s outcome.

It is a time of whispers and shadows.

I met with Irene Joliot-Curie and Frédéric again, this time joined by a quiet but brilliant Hungarian physicist, Leo Szilard, who made his way to Geneva by obscure and dangerous routes. His knowledge of chain reactions and atomic structure is both terrifying and awe-inspiring. He believes that, unless we intervene, someone will succeed in building the bomb—whether it is Heisenberg, the Americans, or even the Soviets. No ideology has a monopoly on destruction.

We spent nights in closed rooms, the smell of chalk and ink mixing with the stale air of urgency. I have never seen Szilard sleep.

What are we to do, then? This is the question that haunts me.

We considered writing to the Allied powers—Roosevelt, Churchill—urging them to prepare, to stay ahead of the Axis in this race toward the abyss. But to do so would mean directly participating in the militarization of science. Have we not learned from the past? Did not my own formula, E=mc², birth this nightmare possibility? I cannot escape the role my thoughts played in opening this door.

In the end, we sent a memorandum—not as a warning, but as a plea.

It was sent through secret diplomatic channels, addressed to neutral scientific contacts in London and New York. In it, we offered our support for monitoring and regulating fission research post-war, calling for an international scientific council that would forbid any nation from constructing a bomb, and for transparency in atomic experimentation.

It is likely the letter will be ignored, perhaps even intercepted. Still, we had to try. We signed it with our names and our conscience.

I am reminded more than ever of Spinoza's words: All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare. There is no easy path forward. The physics is clear, the ethics is not.

Last night, as I walked along Lake Geneva, the sky was heavy with clouds. The stars, hidden. And I thought—not for the first time—of what it would look like if one of those stars fell to Earth in flame, not from nature, but from man.

I can feel the future vibrating on the edge of possibility. Either we find a way to hold this power in common, with wisdom, or it will devour us all.

— A.E.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.