The Quiet Rebellion of Genius

Chapter 10: The Silence of the Atom

May 1941.

The air over Zürich trembles with the dull unease of wartime proximity. Switzerland remains officially neutral, but neutrality is fragile when flanked by fascism. Einstein walks through the corridor of the Federal Polytechnic, now adorned with blackout curtains and guarded entrances. His gait is slower than it was a decade ago, but his eyes remain sharp—burning with restlessness and responsibility.

The Nobel laureate has become more than a physicist: he is now a public symbol, an ethical compass, and increasingly, a political liability.

In the private lab granted by the university, Einstein receives visitors less frequently. His close circle includes a small cadre of students and collaborators—among them, young Swiss physicist Erna Gasser, whose sharp critiques and precise calculations remind him of his earlier self.

Erna brings troubling news that morning.

“They’re mobilizing more uranium in Bavaria,” she says, breathless. “The Gestapo has swept up two of our couriers. And we’ve lost contact with Szilárd in Hungary.”

Einstein pinches the bridge of his nose, his usual tic when confronted with bureaucratic nightmares. But this is worse. The silence around uranium movement means that somewhere, in some fortified basement of the Reich, theoretical physics is being conscripted into service.

“They’re getting close,” he murmurs. “Too close.”

He walks to the blackboard and begins scribbling equations with the urgency of a man trying to outrun history. Fission. Chain reactions. Theoretical thresholds. All the knowledge he once believed too advanced to weaponize is no longer a theoretical exercise—it is a blueprint of terror in enemy hands.

That afternoon, he drafts what will become known as the Zurich Memorandum—a clandestine letter co-authored with Erna and a few trusted others. It outlines what they know of Nazi research into nuclear fission and strongly urges the Allied scientific community—especially in Britain—to accelerate countermeasures. He knows it will be intercepted. He knows it will make him a target. Still, he signs it.

“I am no longer content to be a pacifist when physics has become a weapon. Silence is now complicity.”

News arrives a few days later: Szilárd has managed to escape, barely. But his message is sobering—the Germans have already started construction on a test facility deep in the Black Forest. Einstein’s dread crystallizes.

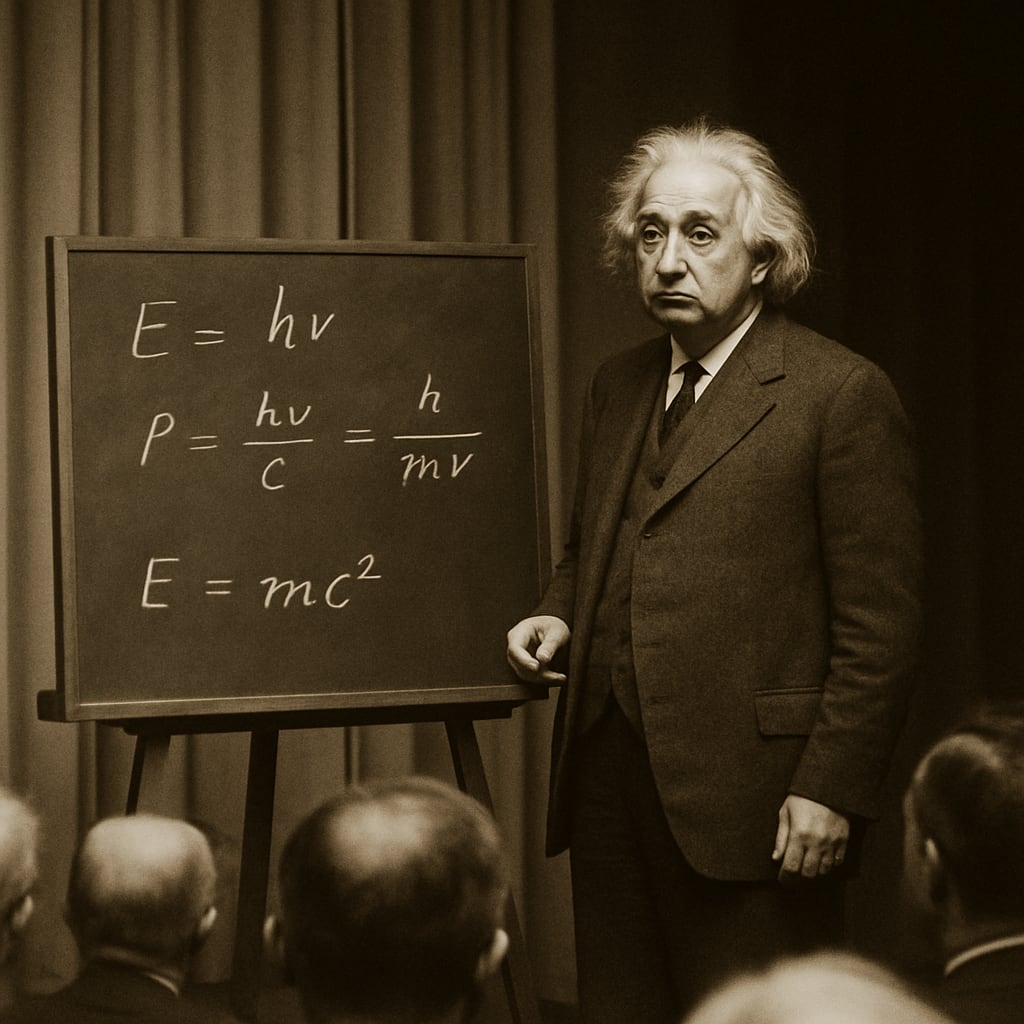

In a rare public appearance, he delivers a speech to the Swiss Physical Society. The hall is tightly packed with students and journalists, eager to hear him speak.

He doesn’t lecture on relativity.

Instead, he delivers a chilling forecast:

“Science is not a neutral force. It follows the contours of the society that wields it. When science is severed from human values, it becomes monstrous. Today we stand on the brink—not of discovery—but of annihilation by discovery.”

The crowd is stunned into silence. The usual applause does not follow.

Later that night, he sits in his dim apartment, radio humming static from across Europe. In a locked drawer, he keeps a small, hand-written list of names—scientists, technicians, engineers—he believes may be useful if the Allies ever listen.

On the back of the list, he’s scribbled a single line:

“The atom speaks, but it does not choose sides. That is left to us.”

As the bells of Zürich toll midnight, Einstein wonders whether the theory he once believed would liberate mankind may, in fact, be its undoing.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.