The Unbroken Equation

Chapter 11 : Geneva, 1937

May 3, 1937

The chill of Lake Geneva drifted through the open window of Einstein’s modest apartment. A kettle hissed on the stovetop while chalk dust floated lazily in the morning sun. He stood before a blackboard crowded with dense notations, pausing only to sip the now-cold tea forgotten on the sill. The room was quiet save for the soft scratch of chalk and the distant clatter of streetcars below. Europe, meanwhile, was anything but quiet.

Rumors from Berlin spoke of a new alliance between the Reich and several Eastern European strongmen. Einstein, now residing in Switzerland under a neutral flag, was surrounded by scientists, diplomats, and exiles whose presence in Geneva was becoming increasingly intentional. What had begun as a personal refusal to endorse American militarism had grown into a small but fierce intellectual haven in the heart of Europe. And Geneva, already the seat of the League of Nations, had taken on a new symbolic gravity thanks to Einstein’s presence.

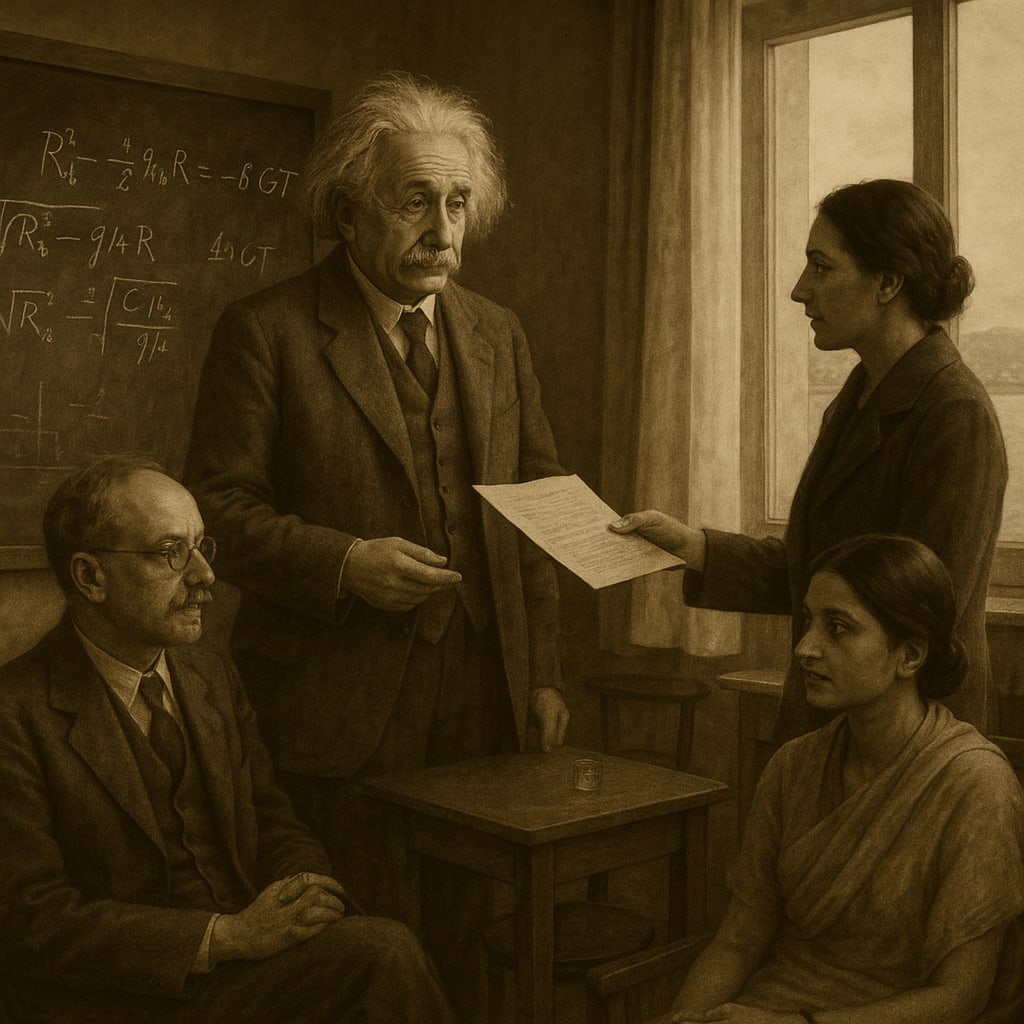

This morning, a visitor waited in the hallway — Marie Curie’s daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie, laureate in her own right and now a liaison between French resistance scientists and Geneva’s radical intellectuals. She stepped inside, coat damp from a morning rain, and unwrapped a carefully sealed envelope.

“They’re asking for your signature,” she said, handing him a folded statement denouncing Franco’s regime in Spain and calling for an international scientific boycott of countries aiding fascist governments.

Einstein read in silence. His pen hovered over the page. “Boycotts do little to shift regimes,” he muttered, “but public silence does even less.” He signed.

Their conversation drifted toward fission, energy, and responsibility. The German atomic program was real, and growing. Einstein had heard whispers through old colleagues still trapped behind the borders — Heisenberg, Hahn. The same minds that once debated quantum uncertainty over wine now toiled under orders to weaponize their discoveries. Einstein felt the tension tighten in his chest again — the same fear that had drawn him to advocate for peace, now pulling him back toward urgent warnings.

That afternoon, at the League of Nations building, Einstein met with a delegation of Scandinavian physicists and pacifists. One of them, a young Danish thinker named Boe Rasmussen, posed a question that would haunt Einstein for months: “If our discoveries become weapons, does that make us their architects or their victims?”

Einstein responded carefully: “We are always both.”

May 12, 1937

News from Italy reached Geneva: Mussolini had issued a public decree offering haven and funding to any scientist willing to work on “national defense through physics.” The offer, cloaked in nationalist grandeur, was aimed at minds like Einstein’s, Niels Bohr’s, and Joliot-Curie’s.

Einstein published a letter the following day in La Revue Scientifique:

“A mind is not for rent to tyrants. The universe is governed by laws that care nothing for borders, blood, or slogans. Our work should serve the dignity of life, not its domination.”

The letter was reprinted across Europe. Within days, his words were quoted by protestors in Warsaw and by a clandestine radio broadcast in Barcelona.

But the walls were closing in. Switzerland’s neutrality was becoming increasingly fragile. And Einstein began to feel the weight of decisions deferred. He convened an evening meeting in his flat — not of scientists, but of artists, writers, and philosophers. He believed that truth needed more than equations to survive. It needed stories, beauty, resistance.

Among the guests were the painter Paul Klee, the composer Arthur Honegger, and a young Indian poet named Mira Sen, a disciple of Tagore. They discussed not bombs or equations, but memory — how the world would remember the truth, if the tyrants wrote the laws of history.

Einstein lit a candle and wrote in his diary:

“If I have failed to stop what’s coming, then let this gathering of souls be the first trace of its antidote.”

The pages would remain unpublished until long after the war. But the idea, like light through a prism, had already begun to split — into voices, movements, ripples.

In Geneva that spring, a war had not yet come. But resistance had already begun.

About the Creator

Alain SUPPINI

I’m Alain — a French critical care anesthesiologist who writes to keep memory alive. Between past and present, medicine and words, I search for what endures.

Comments (1)

Beautifully written