The Evolution of Music at the Dawn of Islamic Civilization: A Study of the Umayyad Period

This article explores how, during the Umayyad era, music evolved from simple entertainment into a cultural and political force shaping Islamic civilization.

The Evolution of Music at the Dawn of Islamic Civilization: A Study of the Umayyad Period

Author: Islamuddin Feroz, Former Professor, Department of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kabul University

Abstract

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE) represents one of the most significant periods in Islamic history, during which music evolved from a marginal practice into a fundamental element of courtly and social culture. With the transfer of the caliphal center to Damascus, the Umayyad court became a site of cultural interaction and exchange among Arab, Persian, Byzantine, and Andalusian civilizations. Although Muʿāwiyah ibn Abī Sufyān initially showed little interest in music, from the reign of Yazīd I onward, music and singing were formally introduced into the court, and renowned musicians and singers such as Salāma al-Qass and Ḥabbāba gained fame. During this period, music was not only a means of entertainment and political display but also played a vital role in shaping the cultural identity of early Islam. A historical examination of this era shows that the Umayyads’ cultural policies, despite religious constraints, provided fertile ground for the expansion of the arts and the transmission of musical traditions to later periods—especially the Abbasid era.

Keywords: Umayyads, court music, Islamic culture, female singers, Damascus, art and power

Introduction

The Umayyad period can be regarded as the first stage in the consolidation of political authority and the formation of civilization in the Islamic world. This era, which began after the political upheavals following the rule of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, marked the beginning of the interconnection between politics, culture, and art within the framework of the Islamic caliphate. With the transfer of the capital to Damascus, the Islamic community came into direct contact with the ancient civilizations of the East and the Mediterranean—encounters that laid the groundwork for profound transformations in the cultural and artistic structures of the Islamic world.

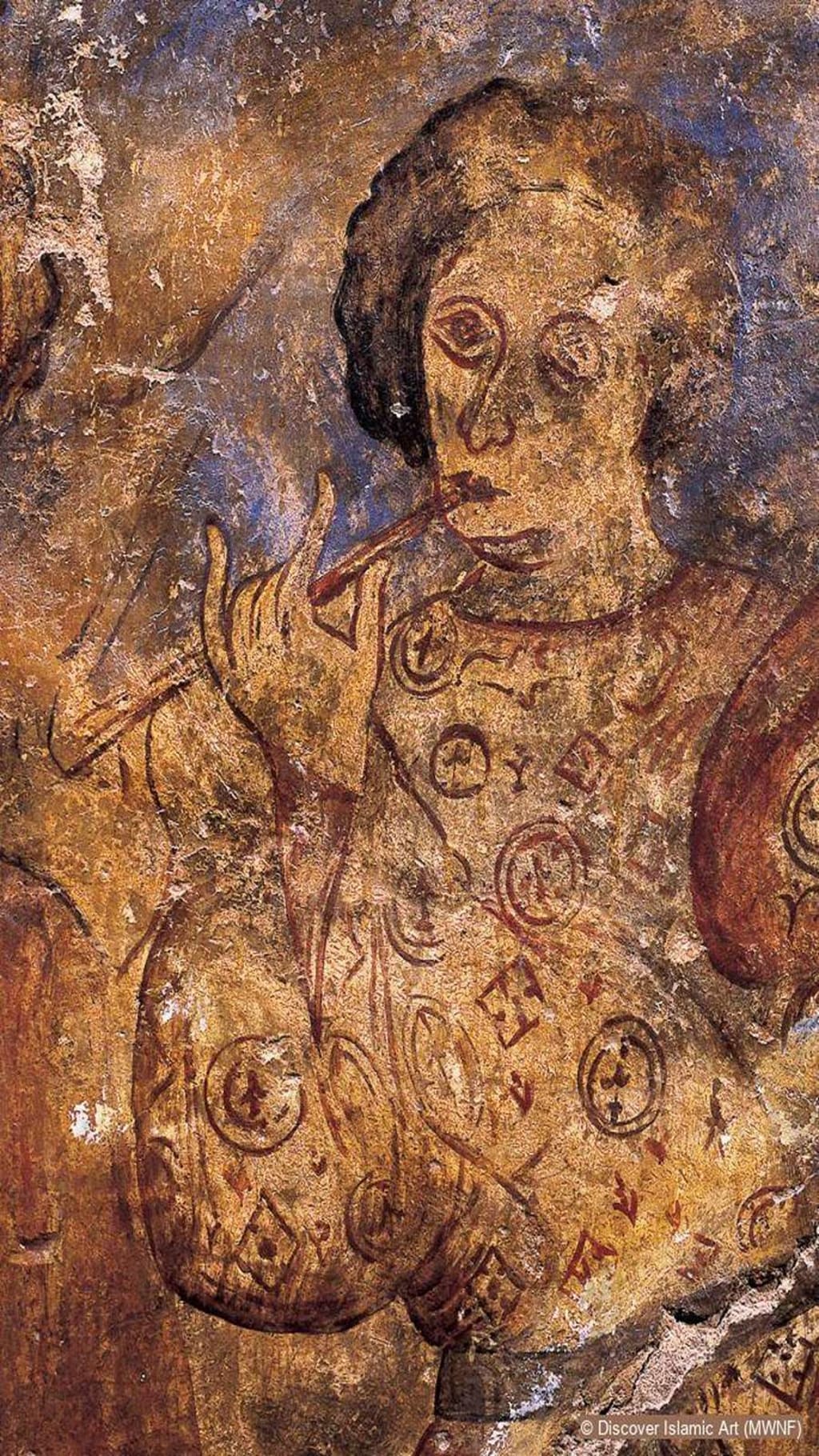

Amid these changes, music assumed a defining role. Although music in early Islam was not widely appreciated due to religious considerations, during the Umayyad era the Damascus court became a hub for singers, instrumentalists, and poets. This development not only reflected a changing attitude toward music but also illustrated the Umayyads’ desire to establish a courtly culture comparable to that of the great preceding empires. Music in this period transcended the level of personal amusement and became a vehicle for expressing power, caliphal grandeur, and the emerging cultural identity of the Muslim community.

The importance of studying Umayyad music lies in the fact that this period laid the cornerstone for Islamic musical traditions and created a cultural model that reached its zenith during the Abbasid era. Historical sources and literary accounts from this period reveal that music was not only part of courtly life but also a significant element of social, educational, and even political interaction. This article seeks, through a historical–analytical approach, to elucidate the position of music during the Umayyad era, the role of artists and singers in shaping courtly culture, and the influence of this legacy on the expansion of Islamic art.

The Expansion of Music During the Umayyad Caliphate

After the turbulent era of the four Rightly Guided Caliphs that began following the death of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Muʿāwiyah—whose sister, Ramla (known as Umm Ḥabībah), was one of the Prophet’s wives—assumed the caliphate. Muʿāwiyah belonged to the same Umayyad clan as the third caliph, ʿUthmān. With the rise of Muʿāwiyah’s rule, the caliphate became hereditary and came to be known as the Umayyad Caliphate, which held power for nearly a century, from 661 to 750 CE. The Umayyads moved the capital of the Islamic Empire to Damascus and launched ambitious campaigns of conquest and construction (Nielson, 2021, p. 37). With the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate, music entered the new court in Damascus and, in subsequent centuries, played an increasingly prominent role in the Arab-Islamic civilization. Nevertheless, Muʿāwiyah (r. 661–680 CE) himself showed little interest in music or singing and reportedly pretended never to have witnessed a singer’s performance. According to researchers, public performances of vocal music accompanied by instruments were first introduced during the reign of his son, Yazīd I (r. 680–683 CE). Yazīd was known for his passion for music (ṭarab) and for hosting wine-drinking gatherings. However, little information exists regarding music during the reigns of the next two caliphs—Muʿāwiyah II (r. 683–684 CE) and Marwān I (r. 684–685 CE)—each of whom ruled for only about a year. Under the next three Umayyad caliphs—ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685–705 CE), al-Walīd I (r. 705–715 CE), and Sulaymān (r. 715–717 CE)—music assumed a more prominent role at court. During this time, prominent singers were invited to perform at the caliphal court. Among them were Salāma al-Qass and Ḥabbāba, who became famous not only for their singing but also for their influence within the court—especially during the reign of Yazīd II (r. 720–724 CE). In 711 CE, when the Muslim army crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to conquer the Iberian Peninsula, both the Arabs and the Iberians possessed rich musical traditions, and both societies were highly multicultural and multilingual. During this period, the music of the Arabian Peninsula came under the influence of new elements from neighboring traditions and underwent a fundamental transformation. A new class of professional singers rapidly emerged, primarily composed of slaves, mawālī, and individuals of mixed heritage. In this system, the world of music was organized based on merit, and talented musicians, regardless of their background, could rise to prominence and even perform at the caliphal court.

At the same time, members of the Arab elite studied, performed, and even composed music privately, while publicly acting as patrons and protectors of singers. They organized concerts and musical competitions, awarded significant prizes to winners, and brought talented individuals into their households as mawālī or slaves, providing them with education in music and poetry (Reynolds, 2021, p. 36). Romantic ghazals emerged as an independent art form, founded by ʿUmar ibn Abī Rabīʿa (d. circa 719 CE) from Mecca. He specialized in praising love for young women who visited the two holy cities of Arabia, expressing his passion with astonishingly beautiful and articulate language (Haris et al., 2020, p. 210).

Thus, from the Umayyad period onward, musical and poetic entertainment, along with the growing number of musicians affiliated with the caliph and the upper classes, became an integral part of courtly culture. Simultaneously, scholars, texts, slaves, and foreign musical technologies flowed into the urban centers of the Islamic states. New vocal styles, songs, and melodic and rhythmic patterns were adopted and integrated into existing musical practices. Vocal and instrumental capacities expanded, yet the permeable boundaries between recited poetry and singing made it difficult to distinguish what constituted music-song and what constituted poetry. Often, this distinction was determined by the performer’s intent, the audience’s perception, and the type of accompaniment, if any. Lavish courtly entertainments—including wine, singing female slaves, and musicians—quickly became a controversial domain and sparked debates regarding the status of music and musical sounds in Islam (Nielson, 2021, p. 34). Although some courtly amusements common in other cultures were prohibited in Islam, the Umayyads recognized that maintaining a strong and wealthy court culture was essential for becoming a global power. Music and having groups of prominent musicians dedicated to court performances were integral to the culture of other royal courts, and the Umayyads supported this trend (Ibid., 2021, p. 37). Female musicians, especially among wealthy and noble classes, acquired a special status. These women, often singing and performing slaves, played a key role in courtly and elite musical culture. Banquets and social gatherings that included music, poetry, and wine-drinking became an inseparable part of the life of the caliphs and political and social elites. Nevertheless, music remained a vital human activity that could not be ignored (Arbor, 2018, p. 28). The Umayyad era was a brilliant period in Islam, during which the caliphate was firmly established. During this time, Islam expanded across vast areas of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Beyond Khorasan, Islam spread to extensive territories from the borders of China and the Indus Valley in the east to the Atlantic coasts and beyond the Pyrenees mountains. With this expansion and the conversion of many peoples, new Muslim communities—including Turks, Barmakids, Persians, and Khorasanis, who were intelligent and powerful—sought to participate in Islamic affairs. At that time, Abū Muslim Khorāsānī (700–755 CE) was the most powerful and renowned military leader in Khorasan. Taking advantage of the unstable conditions under Umayyad rule, he led a rebellion and claimed that the Abbasids were the true successors of the Prophet Muhammad’s family. With his support, the Umayyads were defeated. In 750 CE, Marwān II, the last Umayyad caliph, was killed by the Abbasids. He was succeeded by al-Saffāḥ (r. 750–775 CE) as caliph, and in the same year, Abū Muslim was appointed governor of Khorasan (Israt, Islam, 2013, p. 33). An examination of music during the Umayyad period reveals that this art transcended mere courtly entertainment and gradually became a medium reflecting the intellectual and social transformations of the Islamic community. Unlike the traditional early Islamic view that regarded music solely as a worldly activity, music in this era held a dual status: on one hand, it served the political authority of the caliphate, and on the other, it provided a platform for individual creativity and cultural interaction. The Umayyad caliphs, particularly in the second century AH, recognized that music could serve as a legitimizing tool to display the splendor of the caliphate and courtly order. Musical gatherings featuring poets, singers, and instrumentalists symbolically represented the cultural power of the caliphate and reinforced its legitimacy among the elite. In this context, music became not only a language of beauty but also a language of politics and identity.

On the other hand, the expansion of geographical connections within the Umayyad Empire facilitated a broad exchange of musical traditions. In cities such as Damascus, Medina, and Kufa, music education became more systematic, and theoretical terms related to rhythm, melody, and maqām (musical modes) became widespread. This development can be regarded as the first step toward the “scientification” of Islamic music—a process that later reached its peak during the Abbasid era with the emergence of musicians such as Ishaq al-Mawsili and Ziryab. Historical records indicate that music, contrary to the rigid social hierarchy, partially transcended social boundaries. Many prominent artists, including female singers and freed slaves, attained high social and economic status through their art. This phenomenon demonstrates that music in Umayyad society was not merely an aristocratic pastime but also a channel for social mobility and individual expression. Culturally, music became one of the most effective tools for conveying emotion, historical narrative, and aesthetic values. The close connection between poetry and music allowed Arabic literature to develop into a more auditory and rhythmic form, while music itself transcended purely sonic expression to carry meaning and narrative. Thus, Umayyad music was not merely a reflection of courtly pleasure; it also represented a transformation in the cultural self-awareness of early Muslims.

Nevertheless, music in the Umayyad period can be seen as a multifaceted phenomenon, in which art, politics, society, and religion interacted in complex ways. This era was neither the complete end of pre-Islamic (jahili) traditions nor the mere beginning of Islamic art, but rather a transitional and integrative stage in which the foundations of classical Islamic music were established.

Conclusion

The findings of this research indicate that the Umayyad period marked a turning point in the history of Islamic music—a time when musical art extended beyond oral and local traditions to enter the realms of politics and official culture. Despite religious constraints and criticism from some scholars, the Umayyads recognized the significance of music as a cultural and diplomatic instrument. Court musicians, both male and female, acquired considerable social status, and a new class of professional artists emerged within Islamic society. The study demonstrates that Umayyad music not only influenced the development of instruments and musical styles but also played a fundamental role in shaping the relationship between poetry and music and in establishing Arabic vocal traditions. The presence of female singers and mawālī at court further reflects a level of social and cultural mobility rarely observed in contemporary societies. In conclusion, the Umayyads’ cultural policies, despite apparent contradictions between religion and music, provided a stable framework for the growth of the arts in the Islamic world. The musical legacy of this period inspired the Abbasid era and became a source of influence across Islamic lands, establishing the Umayyads as the founders of the first organized musical system in Islamic civilization.

References

Arbor, Ann. (2018). The modal system of Arabian and Persian music, 1250 - 1500: An interpretation of contemporary texts. Owen Wright. Eisenhower: ProQuest LLC.

Haris, Saidah. Ganesan Shanmugavelu. Hanizah, Abdul Bahar. (2020). musicology in Islam Preliminary study. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR) - Peer Reviewed Journal Volume: 6. Pp 206-213. Haris and others, 2020, p

Israt Ara, Aniba. Islam, Arshad . (2013). Chinggis Khan And His Conquest Of Khorasan: Causes And Consequences. International Islamic University Malaysia.

Nielson, Lisa. (2021). Music and Musicians in the Medieval Islamicate World A Social History. London: I.B. TAURIS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Reynolds, Dwight F. (2021). The Musical Heritage of Al-Andalus. New York: published by Routledge. Reynolds, 2021, P 24

About the Creator

Prof. Islamuddin Feroz

Greetings and welcome to all friends and enthusiasts of Afghan culture, arts, and music!

I am Islamuddin Feroz, former Head and Professor of the Department of Music at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Kabul.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.