Terema Remx

Stories (11)

Filter by community

The history of chocolate

If you can't imagine life without chocolate, you're lucky you weren't born before the 16th century. Until then, chocolate only existed in Mesoamerica in a form quite different from what we know. As far back as 1900 BCE, the people of that region had learned to prepare the beans of the native cacao tree.

By Terema Remx2 years ago in History

A brief history of cannibalism

15th century Europeans believed they had hit upon a miracle cure: a remedy for epilepsy, hemorrhage, bruising, nausea, and virtually any other medical ailment. This brown powder could be mixed into drinks, made into salves or eaten straight up. It was known as mumia and made by grinding up mummified human flesh.

By Terema Remx2 years ago in Fiction

The dark history of zombies

Animated corpses appear in stories all over the world throughout recorded history. But zombies have a distinct lineage one that traces back to Equatorial and Central Africa. The first clue is in the word “zombie” itself. Its exact etymological origins are unknown, but there are several candidates. The Mitsogho people of Gabon, for example, use the word “ndzumbi” for corpse. The Kikongo word “nzambi” refers variously to the supreme being, an ancestor with superhuman abilities, or another deity. And, in certain languages spoken in Angola and the Congo, “zumbi” refers to an object inhabited by a spirit, or someone returned from the dead. There are also similarities in certain cultural beliefs. For example, in Kongo tradition, it’s thought that once someone dies, their spirit can be housed in a physical object which might bring protection and good luck. Similar beliefs about what might happen to someone’s soul after death are held in various parts of Africa. Between 1517 and 1804, France and Spain enslaved hundreds of thousands of African people, taking them to the Caribbean island that now contains Haiti and the Dominican Republic. There, the religious beliefs of enslaved African people mixed with the Catholic traditions of colonial authorities and a religion known as “vodou” developed. According to some vodou beliefs, a person’s soul can be captured and stored, becoming a body-less “zombi.” Alternatively, if a body isn’t properly attended to soon after death, a sorcerer called a “bokor” can capture a corpse and turn it into a soulless zombi that will perform their bidding. Historically, these zombis were said to be put to work as laborers who needed neither food nor rest and would enrich their captor’s fortune. In other words, zombification seemed to represent the horrors of enslavement that many Haitian people experienced. It was the worst possible fate: a form of enslavement that not even death could free you from. The zombi was deprived of an afterlife and trapped in eternal subjugation. Because of this, in Haitian culture, zombis are commonly seen as victims deserving of sympathy and care. The zombie underwent a transformation after the US occupation of Haiti began in 1915 this time, through the lens of Western pop culture. During the occupation, US citizens propagated many racist beliefs about Black Haitian people. Among false accounts of devil worship and human sacrifice, zombie stories captured the American imagination. And in 1932, zombies debuted on the big screen in a film called “White Zombie.” Set in Haiti, the film’s protagonist must rescue his fiancée from an evil vodou master who runs a sugar mill using zombi labor. Notably, the film's main object of sympathy isn't the enslaved workforce, but the victimized white woman. Over the following decades, zombies appeared in many American films, usually with loose references to Haitian culture, though some veered off to involve aliens and Nazis. Then came the wildly influential 1968 film “Night of the Living Dead,” in which a group of strangers tries to survive an onslaught of slow-moving, flesh-eating monsters. The film’s director remarked that he never envisioned his living dead as zombies. Instead, it was the audience who recognized them as such. But from then on, zombies became linked to an insatiable craving for flesh with a particular taste for brains added in 1985′s “The Return of the Living Dead.” In these and many subsequent films, no sorcerer controls the zombies; they’re the monsters. And in many iterations, later fueled by 2002′s “28 Days Later,” zombification became a contagious phenomenon. For decades now, artists around the world have used zombies to shine a light on the social ills and anxieties of their moment from consumer culture to the global lack of disaster preparedness. But, in effect, American pop culture also initially erased the zombies origins cannibalizing its original significance and transforming the victim into the monster.

By Terema Remx2 years ago in Fiction

Why was India split into two countries?

In August 1947, India gained independence after 200 years of British rule. What followed was one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in history. An estimated one million people lost their lives. Before British colonization, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of regional kingdoms known as princely states populated by Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Parsis, and Jews. Each princely state had its own traditions, caste backgrounds, and leadership. Starting in the 1500s, a series of European powers colonized India with coastal trading settlements. By the mid-18th century, the English East India Company emerged as the primary colonial power in India. The British ruled some provinces directly, and ruled the princely states indirectly. Under indirect rule, the princely states remained sovereign but made political and financial concessions to the British. In the 19th century, the British began to categorize Indians by religious identity a gross simplification of the communities in India. They counted Hindus as “majorities” and all other religious communities as distinct “minorities,” with Muslims being the largest minority. Sikhs were considered part of the Hindu community by everyone but themselves. In elections, people could only vote for candidates of their own religious identification. These practices exaggerated differences, sowing distrust between communities that had previously co-existed. The 20th century began with decades of anti-colonial movements, where Indians fought for independence from Britain. In the aftermath of World War II, under enormous financial strain from the war, Britain finally caved. Indian political leaders had differing views on what an independent India should look like. Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru represented the Hindu majority and wanted one united India. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who led the Muslim minority, thought the rifts created by colonization were too deep to repair. Jinnah argued for a two nation division where Muslims would have a homeland called Pakistan. Following riots in 1946 and 1947, the British expedited their retreat, planning Indian independence behind closed doors. In June 1947, the British viceroy announced that India would gain independence by August, and be partitioned into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan— but gave little explanation of how exactly this would happen. Using outdated maps, inaccurate census numbers and minimal knowledge of the land, in a mere five weeks, the Boundary Committee drew a border dividing three provinces under direct British rule: Bengal, Punjab, and Assam. The border took into account where Hindus and Muslims were majorities, but also factors like location and population percentages. So if a Hindu majority area bordered another Hindu majority area, it would be included in India but if a Hindu majority area bordered Muslim majority areas, it might become part of Pakistan. Princely states on the border had to choose which of the new nations to join, losing their sovereignty in the process. While the Boundary Committee worked on the new map, Hindus and Muslims began moving to areas where they thought they’d be a part of the religious majority but they couldn’t be sure. Families divided themselves. Fearing sexual violence, parents sent young daughters and wives to regions they perceived to be safe. The new map wasn’t revealed until August 17th, 1947 two days after independence. The provinces of Punjab and Bengal became the geographically separated East and West Pakistan. The rest became Hindu-majority India. In a period of two years, millions of Hindus and Sikhs living in Pakistan left for India, while Muslims living in India fled villages where their families had lived for centuries. The cities of Lahore, Delhi, Calcutta, Dhaka, and Karachi emptied of old residents and filled with refugees. In the power vacuum British forces left behind, radicalized militias and local groups massacred migrants. Much of the violence occurred in Punjab, and women bore the brunt of it, suffering rape and mutilation. Around 100,000 women were kidnapped and forced to marry their captors. The problems created by Partition went far beyond this immediate deadly aftermath. Many families who made temporary moves became permanently displaced, and borders continue to be disputed. In 1971, East Pakistan seceded and became the new country of Bangladesh. Meanwhile, the Hindu ruler of Kashmir decided to join India a decision that was to be finalized by a public referendum of the majority Muslim population. That referendum still hasn't happened as of 2020, and India and Pakistan have been warring over Kashmir since 1947. More than 70 years later, the legacies of the Partition remain clear in the subcontinent: in its new political formations and in the memories of divided families.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Education

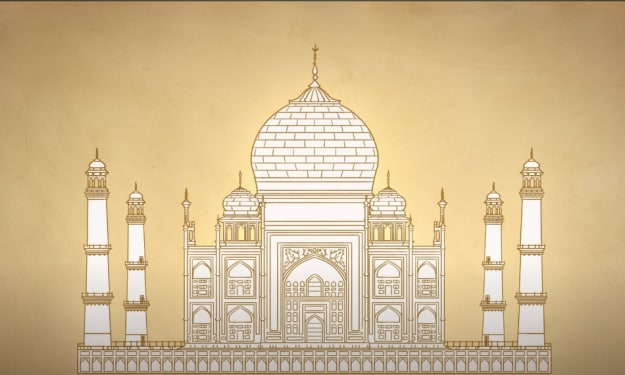

The most beautiful building in the world

It’s 1631 in Burhanpur, and Mumtaz Mahal, beloved wife of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, is giving birth to their 14th child. A healthy girl is born, but not without difficulty. Shah Jahan rushes to Mumtaz’s side, but he cannot save her. Sobbing uncontrollably, the emperor decides to build a tomb worthy of his queen: an earthly replica of Paradise to embody their perfect love and project the power of the Mughal Empire for all time. Construction of the Taj Mahal began roughly seven months later. Royal architects worked to bring Shah Jahan’s vision to life at a site chosen by the emperor in the bustling imperial city of Agra. The Yamuna riverfront was already dotted with exquisite residences, gardens, and mausoleums. But when complete, the Taj Mahal would be the most magnificent structure of all. In addition to housing Mumtaz’s mausoleum, the plans included a garden, mosque, bazaar, and several caravanserais to house visiting merchants and diplomats. Together, this complex would seamlessly blend Persian, Islamic, Indian, and European styles, establishing the Taj Mahal as the culmination of Mughal architectural achievement. The entire compound was laid out on a geometric grid, incorporating meticulously planned bilateral symmetry. To further establish an atmosphere of balance and harmony, the architects divided the complex into two spheres, representing the spiritual and earthly domains. Most of the structures were made of brick and red sandstone, with white marble accents. This was a common motif in Mughal architecture, inspired by ancient Indian traditions associating white with spiritual purity and red with warriors and royalty. But the central mausoleum took more inspiration from the Islamic tradition. Framed by four minarets, the structure was covered entirely in white marble from quarries over 400 kilometers away. Its main dome towered above the skyline, and those within the cavernous chamber experienced an otherworldly echo lasting almost 30 seconds. Perfecting the Italian stone-working technique, pietra dura, craftsmen used all manner of semi-precious stones to create intricate floral designs representing the eternal gardens of Paradise. Calligraphers covered the walls with Quranic inscriptions. And because the Islamic depiction of Paradise has eight gates, the mausoleum’s rooms were designed to be octagonal. The garden in front of the mausoleum was split into four parts in the Persian style, but its flora reflected the Mughals’ nomadic Central Asian heritage. Flowers and trees were carefully selected to add color, sweet scents, and fresh fruit to be sold in the bazaar. Masons built intersecting walkways, pools, and channels of water to weave through the lush greenery. Even before its completion, Shah Jahan used the Taj to host the annual commemoration of Mumtaz’s death, celebrating her reunification with the Divine. Directly across the river, Shah Jahan built another sprawling garden with a central pool that perfectly reflected the mausoleum. Building this intricate complex took 12 years and employed thousands of skilled craftsmen and artisans, from masons and bricklayers to masters of pietra dura and calligraphy. After the Taj was completed in 1643, Shah Jahan retained some of these craftsmen for routine repairs, and hired Quran reciters, caretakers, and other staff to maintain the complex. He paid these workers by establishing a vast endowment for the Taj— a system which remained in place until the early 19th century. Since its completion, Shah Jahan’s grand memorial has drawn travelers from around the world. And every time a visitor is awed by the mausoleum, the emperor’s goal is achieved anew. Unfortunately, after 15 years of presiding over Mumtaz’s memorial, Shah Jahan fell ill and a war of succession broke out between his sons. While Shah Jahan eventually recovered, his son, Aurangzeb, had already emerged as the new emperor. For the last eight years of his life, Shah Jahan lived under house arrest in Agra’s Fort, where he could see the Taj glimmering in the distance. When he died in 1666, he was buried next to Mumtaz, his grave breaking the complex’s symmetry, so that his wife could remain at the Taj’s center for all eternity. This video was made possible with support from Marriott Hotels. With over 590 hotels and resorts across the globe, Marriott Hotels celebrates the curiosity that propels us to travel. Check out some of the exciting ways TED-Ed and Marriott are working together and book your next journey at Marriott Hotels.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Education

The rise and fall of the Mughal Empire

It’s 1526 in what is now Northern India, and Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi is about to face off against a prince from Central Asia, Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur. To quash the threat, the Sultan brings his war elephants to battle. But it’s said that the explosions of Babur’s cannons and muskets startled the elephants and they trampled the Sultan’s own army. Babur had long harbored ambitions of building his own empire. Though he was descended from some of the world’s most successful conquerors, he struggled to gain a foothold among the many ambitious princes in Central Asia. So he turned his attention to India, where his descendants stayed and built the Mughal Empire, one of the wealthiest and most powerful states in the early modern world and home to nearly a quarter of the global population. Babur died just four years after that fateful battle, but his own memoirs and the work of his descendants immortalized him in colorful fashion. His daughter, Gulbadan, recalled in her own memoir how Babur having recently given up drinking filled a newly-constructed pool with lemonade rather than wine. His grandson, Akbar, commissioned exquisite miniature paintings of Babur’s stories one depicted the empire’s founder riding through his camp, drunkenly slumped over his horse. It was Akbar who consolidated Mughal power. He established protections for peasants which in turn increased their productivity and generated more tax revenue and embarked on military campaigns to expand Mughal territory. Princes who swore allegiance to him were rewarded, while he made brutal examples of those who resisted, killing them and many of their subjects. His conquests opened access to port cities on the Indian Ocean, which connected the Mughals to Arab, Chinese, Ottoman, and European traders, bringing in incalculable wealth, including silver and new crops from the Americas. As the Muslim ruler of a diverse, multiethnic empire, Akbar worked to create internal cohesion by appointing members of the Hindu majority to high positions in his government, marrying a Hindu bride, and distributing translated copies of the “Mahabharata,” an ancient Indian epic poem, to his Muslim nobles. Akbar also hosted lively religious debates where Sunni and Shia Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Zoroastrians, and the newly arrived Portuguese Jesuit missionaries defended the merits of their respective faiths. While most participants viewed this as an intellectual exercise, Portuguese missionaries were disappointed by their failure to convert Akbar. The Mughals built architectural masterpieces such as the Taj Mahal and the Red Fort, a palace three kilometers around, that housed 50,000 people and contained the magnificent gold and jewel-encrusted Peacock Throne. Just the throne took seven years to construct. During its first 180 years, the Mughals had only six rulers, which contributed to the empire’s stability. When the fourth emperor, Jahangir, struggled with alcohol and opioid addiction, his wife, Nur Jahan, took the reins as co-ruler. When a traitorous general captured her husband in an attempted coup, she negotiated his release and rallied the army to stop the rebellion. She once led a hunting party to track down a tiger that was terrorizing a village, leading one poet to write: “Though Nur Jahan be in form of a woman In the ranks of men she’s a tiger-slayer.” Following the death of the sixth emperor, Aurangzeb, in 1707, seven emperors took the throne over the next 21 years. These frequent transitions of power reflected the larger political, economic, social, and environmental crises that plagued the empire throughout the 18th century. In response to this turmoil, regional leaders started refusing to pay taxes and broke away from Mughal control. The British East India Company offered military support to these regional rulers, which in turn increased the company's political influence, enabling it to eventually take direct control of Bengal, one of the wealthiest regions in India. By the 19th century, the East India Company had massive political influence and a large standing army, which included Indian troops. When these troops revolted in 1857, aiming to force out the British and restore Mughal influence, the British government intervened, replacing company rule with direct colonial rule, deposing the last Mughal emperor and sending him into exile. And so, over three centuries after its founding, the Mughal Empire came to an end.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Education

One of history's most dangerous myths

From the 1650s through the late 1800s, European colonists descended on South Africa. First, Dutch and later British forces sought to claim the region for themselves, with their struggle becoming even more aggressive after discovering the area’s abundant natural resources. In their ruthless scramble, both colonial powers violently removed numerous Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands. Yet despite these conflicts, the colonizers often claimed they were settling in empty land devoid of local people. These reports were corroborated in letters and travelogues by various administrators, soldiers, and missionaries. Maps were drawn reflecting these claims, and prominent British historians supported this narrative. Publications codifying the so-called Empty Land Theory had three central arguments. First, most of the land being settled by Europeans had no established communities or agricultural infrastructure. Second, any African communities that were in those regions had actually entered the area at the same time as Europeans, so they didn’t have an ancestral claim to the land. And third, since these African communities had probably stolen the land from earlier, no-longer-present Indigenous people, the Europeans were within their rights to displace these African settlers. The problem is that all three of these arguments were completely false. Almost none of this land was empty and Africans had lived here for millennia. Indigenous South Africans simply had a different practice of land ownership from the Dutch and British. Land belonged to families or groups, not individuals. And even that ownership was more focused on the land’s agricultural products than the land itself. Community leaders would distribute seasonal land rights, allowing various nomadic groups to graze cattle or forage for vegetation. Even the groups that did live in large agricultural settlements didn’t believe they owned the land as private property. But the colonizing Europeans had no respect for this system of ownership. They concluded the land belonged to no one and could therefore be divided amongst themselves. In this context, claims that the land was “empty” were an ignorant oversimplification of a much more complex reality. But the Empty Land Theory allowed British academics to rewrite history and minimize native populations. In 1894, the European parliament in Cape Town took this exploitation even further by passing the Glen Grey Act. This decree made it functionally impossible for native Africans to own land, shattering the system of collective tribal ownership and creating a class of landless people. To justify the theft, Europeans painted the locals as barbarians who lacked the capacity for reason and were better off being ruled by the colonizers. This strategy of stripping locals of their right to ancestral lands and casting native people as savages has been employed by many colonizers. Now known as the Empty Land Myth, this is a well-established technique in the colonial playbook, and its impact can be found in the history of many countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United States. And in South Africa, the influence of this narrative can be traced directly to a brutal campaign of institutionalized racism. Barred from their lands, the once self-sufficient population struggled as migrant laborers and miners on European-owned property. The law forbade them from working certain skilled jobs, and forced Africans to live in racially segregated areas. Over time, these racist policies intensified, mandating separation in urban areas, restricting voting rights, and eventually building to apartheid. Under this system, African people had no voting rights, and the education of native Africans was overhauled to emphasize their legal and social subservience to white settlers. This state of legally enforced racism persisted through the early 1990s, and throughout this period, colonists frequently invoked the Empty Land Theory to justify the unequal distribution of land. South African resistance movements fought throughout the 20th century to gain political and economic freedom. And since the 1980s, South African scholars have been using archaeological evidence to correct the historical record. Today, South African schools are finally teaching the region's true history. But the legacy of the Empty Land Myth still persists as one of the most harmful stories ever told.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Education

The rise and fall of Italy’s warriors for hire

At dawn on July 29th, 1364, John Hawkwood an English soldier turned contract mercenary led a surprise attack against an army of sleeping Florentine mercenaries. The enemy commander quickly awoke and gathered his men to launch a counterattack. But as soon as the defending army was ready to fight, Hawkwood’s fighters simply turned and walked away. This wasn't an act of cowardice. These mercenaries, known as condottieri, had simply done just enough fighting to fulfill their contracts. And for Italy’s condottieri, war wasn’t about glory or conquest: it was purely about getting paid. For much of the 14th and 15th centuries, the condottieri dominated Italian warfare, profiting from and encouraging—the region’s intense political rivalries. The most powerful of these regions were ruled either by wealthy representatives of the Catholic Church or merchants who’d grown rich from international trade. These rulers competed for power and prestige by working to attract the most talented artists and thinkers to their courts, leading to a cultural explosion now known as the Italian Renaissance. But local rivalries also played out in military conflicts, fought almost entirely by the condottieri. Many of these elite mercenaries were veterans of the Hundred Years’ War, hailing from France and England. When that war reached a temporary truce in 1360, some soldiers began pillaging France in search of fortune. And the riches they found in Catholic churches drew their raiding parties to the center of the Church’s operations: Italy. But here, savvy ruling merchants saw these bandits’ arrival as a golden opportunity. By hiring the soldiers as mercenaries, they could control the violence and gain an experienced army without the cost of outfitting and training locals. The mercenaries liked this deal as well, as it offered regular income and the ability to play these rulers off each other for their own benefit. Of course, these soldiers had to be kept on a tight leash. Rulers forced them to sign elaborate contracts, or condotta, a word that became synonymous with the mercenaries themselves. Divisions of payment, distribution of plunder, non-compete agreements it was all spelled out clearly, making war merely another dimension of business. Contracts specified the number of men a commander would provide, and the resulting armies ranged from a few hundred to several thousand. Individual soldiers regularly moved between armies in search of higher payments. And when their contracts expired, condottieri commanders became free agents with no expectation of ongoing loyalty. When John Hawkwood launched his surprise attack against the Florentine condottieri, he was working for Pisa. Later, he would fight for Florence and many of Pisa’s other enemies. But regardless of who was contracting them, the condottieri fought primarily for themselves. Their extensive military experience allowed them to avoid taking unnecessary risks in the heat of battle. And while still deadly their clashes rarely led to crushing victories or defeats. Condottieri commanders wanted battles to be inconclusive after all, if they established peace, they’d put themselves out of business. So even when one side did win, enemy combatants were typically held hostage and released to fight another day. But there was nothing merciful about these decisions. Contracts could just as easily turn them into ruthless killers, as in 1377, when Hawkwood led the massacre of a famine-stricken town who’d tried to revolt against the local government. Over time, foreign condottieri were increasingly replaced by native Italians. For young men from humble origins, war-for-profit offered an attractive alternative to farming or the church. And this new generation of condottieri leveraged their military power into political influence, in some cases even founding ruling dynasties. However, despite cornering the market on Italian warfare for nearly two centuries, the condottieri only truly excelled at engaging in just enough close-range combat to fulfill their contracts. Over time, they became outclassed by the gunpowder weaponry of France and Spain’s large standing armies, as well as the naval might of the Ottomans. By the mid 16th century, these state-sponsored militaries forced all of Europe into a new era of warfare, putting an end to the condottieri’s conniving war games.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Education

How About a Singing Black Hole in Our Galaxy?

Space dark lifeless and quiet right well apparently it's not always true recently scientists have detected an eerie Echo coming from the main black hole in our galaxy it has high and low notes and sounds pretty otherworldly what does it mean should we sound the alarm Bell siren whatever Sagittarius A star is our own supermassive black hole sitting right in the center of the Milky Way galaxy where we live you might know that black holes are the true Monsters of our universe gobbling up everything that is careless enough to come to close if a massive black star runs out of its star fuel it sometimes becomes super dense and buckles under its own weight collapsing Inward and bringing space time along as a result the gravitational field of this new thing becomes so strong that nothing can escape it not even light and so goes a black hole we really can't see black hole since they devour everything even light but we can still figure out where they're located all thanks to the existence of accretion discs want an explanation well picture a black hole the starving thing consumes all the matter that Strays Too Close squeezing it into a superheated disc of glowing gas the black hole also bends light around it which creates a circular shadow that's what I mean we can't see a black hole itself but we can see the accretion disc surrounding it.

By Terema Remx3 years ago in Fiction