What Is Text-Based Art? Better Definitions Reflecting Art Histories, Plural, of a Truly Worldwide Form of Art

What is text-based art? Any art form that uses language as art in any way -- as seen in every culture and continent across time for the past five-thousand years. Part I of One Artist's Studio Research -- By Adam Daley Wilson

This Artist's Studio Research Paper Is A First Attempt To Answer Some of These Questions From A World-Wide Perspective:

What Are Better Definitions of Text-Based Art?

What do Global Art Critics Say About Word Art?

What’s the History of Language As Art Worldwide?

Contents

1. The Possibility of Text Based Art as a Common Art Language for Global Thinkers and Critics.

The Similarities Across Cultures are Striking.

2. In Text-Based Art Histories Across Continents and Cultures, a Shared Global DNA.

Recognizing All Text-based Art Histories, Plural.

A Partial Bibliography Will Appear At The End of the Second Part Of This Paper.

1. What Is Text-Based Art? Global Art Critics on The History and Possibilities Of Language As Art.

The following overviews are only short summaries of just a few of the writings, theories, and criticisms of these art critics, curators, art theorists, art scholars, and artist-critics, who in turn are just a few of the thinkers and writers in these areas and fields worldwide. That said, based on research of them so far, my tentative conclusions about global text-based art include that—despite often fundamental and even acute differences in philosophical systems, thinking systems, religious influences, and political, economic, and social structures and assumptions, text-based art is (a) evidenced as an art form almost everywhere on the planet for (b) many of the same philosophical, artistic, and concrete reasons.

Broadly speaking, those reasons appear to be that text-based art—loosely and broadly defined here as any visual art that uses words, language, characters, or language-symbols in some way—affords artists, no matter where they are globally, across continents, countries, and cultures, an artistic aesthetic and a means of artistic expression that can address, explore, and wonder with curiosity about:

· Our most concrete and present issues and needs;

· Our most abstract and philosophical questions about both the intellectual head and the emotional heart;

· Our questions about our languages themselves; and

· Our questions about art itself, including, what is art?

Asia

China

The Chinese art critic and curator Li Xianting, who has also made contributions to avant-garde art in China, might view text-based art primarily as associated with activist art, as a means of challenging established cultural and political norms, using language as a tool not just of critique but also of various degrees of subversion. He might be among those global art critics who take interest in text-based artists who use language in innovative and even imaginary ways, such as Xu Bing, the artist, professor, MacArthur Fellow, and former vice-president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, who has used text and fictitious Chinese characters to question the reliability of communicating through any language, on the theory that the very nature of language allows not just for ambiguities and interpretation but also profound exploitation and manipulation.

Japan

The Japanese contemporary artist and critic Yoshitomo Nara, whose work is seen to be able to bridge both high art and low art, and both the East and the West, might see text-based art not just as an art form for expressing social and political commentary, but also as a way to express personal and human feelings in a complex way. Nara might also see text-based art useful both aesthetically and conceptually as a means of disrupting not only traditional forms and mediums of art, but also as a means of disrupting a viewer’s assumptions and expectations, such as by text works that offer an initial illusion of one set of emotions, feelings, or ideas, but in fact offer interpretations inviting contemplation of very different emotions or ideas. Nara might also see text-based art as being able to push boundaries of what is considered to be art, and as a way to disrupt traditional forms of visual art.

Vietnam

Vietnamese art critic Phan Cam Thuong, who has written on the intersection of art and politics, might see text-based art as a way to challenge the dominant narratives and ideologies, and further as a means of political dissent through the possible use of art and text to subvert traditional and entrenched power structures. Thuong might also see text-based art as a means by which artists can both document and amplify the voices and traditions of marginalized communities and cultural groups in Vietnam.

Africa

Ethiopia

The Ethiopian curator, anthropologist, and writer Meskerem Assegued, who was a member of the selection committee for the 2007 Venice Biennale African Pavilion, and who has written on contemporary art practices in Ethiopia and Africa, might see text-based art as an art form that allows artists to offer interpretations about the interaction between language, culture, and identity in Ethiopia. Her writings suggest that she might also see text-based art as a way to challenge traditional notions of Ethiopian art and culture and to create spaces for marginalized voices, and might see ways in which text-based art can be used to create new forms of expression to engage with complex political and social issues in Ethiopia, and perhaps also across the continent.

Nigeria

Chika Okeke-Agulu, the artist, art historian, Princeton University professor, and British Academy Fellow, is a Nigerian art critic and curator who has written about, and curated shows about, several aspects of contemporary art in Nigeria, as well as art during late twentieth-century dictatorships in Nigeria. Based on his publications, he might see art with words as an artistic expression through which artists can experiment with, and offer, new possible meanings, open to interpretations, about not just contemporary Nigeria but also the historical relationships between language, culture, and identity within Nigeria, specifically the intersection of globalization with Nigeria’s cultures and identities, as well as issues in Nigeria during and after colonialism.

Tunisia

The Tunisian art critic and poet Souad Guellouz, and the Tunisian art critic Sonia Hamza, might each see text-based art as an artistic medium that could be used to express complexities of contemporary Tunisian society—such as Tunisia’s intersections between Tunisia’s art and politics, its traditions as juxtaposed against its modern norms, between past and present modes of thinking, and between the individual as distinct from the collective. They might also see text-based art as a way to create new modes of language expression that not only reflect realities and possibilities of Tunisia, but which also provide for greater world access to Tunisia’s contemporary art and contemporary artists, a point especially made in art criticism writings by Hamza.

Uganda

The Ugandan art critic Eria Solomon Nsubuga, known as SANE, is a contemporary Ugandan painter and art lecturer. With a chosen designation as a social artist, and given that his practice explores the politics of climate, allocation of natural resources, morality, and spirituality, he might see text-based art as a form or medium of art that can provide not only for social and political critique—and more specifically as a way to challenge the status quo and to raise awareness about structural inequalities in Ugandan society—but also as a way to invite new perspectives on traditional notions of spiritual and religious iconography, beliefs about resource possession, and the contradiction of corruption within leaders claiming to be of religious faith. For Nsubuga, text-based art might be a way to give voice to both people and to issues that are marginalized and silenced, as well as to be an affirmative means for social and political change with respect to some of the concrete issues mentioned above.

Central America

Guatemala

The Guatemalan poet and art critic Luis Cardoza y Aragón might see the use of language as a medium itself in the context of art, and might see text-based art as a way to explore the relationship between image and word as a function of visual and linguistic aspects of communication. He might also see the use of text in art as a way to connect with cultural and historical literary traditions.

Eastern Europe

Poland

Karol Irzykowski, a Polish critic who wrote about both film and visual arts, might have seen text-based art as a form of visual poetry, where text stands not just for its linguistic meanings but also for its own aesthetic qualities, depending how presented.

Global Indigenous Peoples

Cree

The Cree scholar, writer, and artist Karyn Recollet, who has written about the intersection of art, activism, and decolonization, often in connection with modern urban spaces, might see text-based art as an aesthetic vehicle for engaging with these topics and issues, possibly using language in text art for both conversation and resistance. She might find of interest those text artists who incorporate text into their practices as a means of challenging dominant narratives, while at the same time promoting disenfranchised cultures, knowledge systems, and perspectives. For example, she might favorably view the work of Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield, whose works with text address some of these issues in the context of cultural identity and political power.

Māori

The Māori scholar, professor, and critic Linda Tuhiwai Smith has written on the relationship between Western and Indigenous knowledge systems, including critical analyses of how Western scholarly research paradigms impede social justice during the colonialization of indigenous cultures. Professor Smith might see text-based art as holding the possibility of critiquing the intersections of language, culture, identity, social justice, and colonialization of societies, with an emphasis of documenting not just indigenous languages and but also indigenous knowledge systems. As such, she might be interested in text artists who both preserve indigenous knowledge and culture and also affirmatively assert it, such as the Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore, whose text-based visual works have addressed some of the types of colonialism and identity issues that Professor Smith has written about and critiqued.

Pueblo

The Pueblo poet and writer Simon Ortiz, known in part for his participation in the second wave of the Native American Renaissance, and who has written on issues of Indigenous identity and culture, including the preservation of literary and oral histories, might see text-based art as a form of art capable of not just preserving those histories but also engaging with them, to document perspectives and present new interpretations. He might see with interest the work of text artist Marie Watt, who is enrolled in the Seneca Nation of Indians, who sometimes uses text and symbols in exploring the full diversity of Northern Hemisphere Native American histories and mythologies in her practice.

India

The Indian curator and art critic Geeta Kapur, known for her writings on modern and contemporary art in India, might see text-based art as an aesthetic useful for exploring assumptions within language, identity, and power. She might find of interest artists who use language to reclaim lost or misappropriated cultural and historical narratives, such as the contemporary Indian artist Nalini Malani, whose practice sometimes uses words and phrases in her visual works on these subjects in India.

The Indian art critic Ranjit Hoskote might see text-based art as a tool for political and social critique, specifically as a way to both challenge the status quo and attempt to subvert dominant political power structures. Hoskote might also see text-based art as a way to explore the intersections between art, politics, and society, and to question cultural assumptions that underlie them.

Middle East

Egypt

The Egyptian art critic Tarek El-Ariss, who has written on the intersection of art, literature, and politics, might, like other critics discussed here, see text-based art as a medium of expression uniquely able to expressly discuss relationships between language, power, and identities in Egypt. He might also see text-based art as a means of challenging established narratives of Egyptian society by creating new artistic spaces for marginalized voices. He might also focus on the ways in which text-based art could be used to explore nuances of Egyptian culture to create a more inclusive and diverse art scene in both Egypt.

Iran

Shahram Karimi is an artist and art critic in Iran who has written about the relationships and interplay of art and broader culture. Karimi might see art with words as allowing artists a means of exploring complexities in the relationships between language itself and broader cultural and historical identities. Like other art critics and scholars discussed here, he might see text-based art as a means of confronting established or entrenched cultural narratives in order to explore under-represented voices in Iranian society. Karimi might particularly appreciate the ways in which text-based art can be used by artists to express emotions and ideas in ambiguous layers that can be interpreted in different ways to engage viewers with elements of Iranian culture.

Iraq

The Iraqi art critic Nada Shabout might view text-based art as an artistic medium for investigating the cultural and historical facts of contemporary Iraq and the Arab world. She might see text-based art as a way to present new narratives that shape a viewer’s understanding of Iraq, and more broadly the Middle East, and to create and express alternative viewpoints that reflect the broader diversity and fuller richness of Iraq’s many cultures and voices. For Shabout, text-based art might be a way to reclaim the histories and cultural heritages within Iraq, and to both document as well as amplify its internal histories in the context of the larger world.

Ali Assaf, another Iraqi artist who has written on contemporary art practices in the Middle East, might see text-based art as useful for exploring the same intersections identified by other art critics, including the intersections of language, culture, and identity in Iraq. He might focus particularly on text-based art in the context of amplifying marginalized voices and in the context of creating new forms of contemporary expression altogether, to examine contemporary political and social issues in Iraq.

Tamara Chalabi is a third Iraqi art critic who is also known for her engagement with contemporary art practices in Iraq. Like other critics discussed in this paper, Chalabi might likely see text-based art as important not just as a form or genre of art, but for serving as a form of expression that can engage with relationships between language, culture, voices, and identities in Iraq. She might see text art specifically as an aesthetic form that can also question traditional notions of Iraqi art, as well as the notion of art itself.

Israel

The Israeli art critic Gideon Ofrat, who has written about the relationships between art and politics, might see text-based art as a way to explore the complex political and cultural relationships between Israeli and Palestinian identities. He might particularly see text-based art as a means of documenting and juxtaposing the contemporary and historical perspectives of both Israeli and Palestinian voices. Ofrat might also consider text art as possibly facilitating new perspectives for dialogue and understanding.

Palestine

The Palestinian art critic Kamal Boullata might have seen art with words as an artistic medium able to both express and document experiences of displacement. He particularly might have seen text-based art as a way to articulate emotions and feelings about contemporary political experiences in relation to identity and place. He might also have seen text art as a form of aesthetic expression that can explore relationships between cultural histories, political histories, and cultural memories, including across borders. He might have seen text-based art as uniquely available to create layered and ambiguous meanings allowing for new interpretations of complex political dynamics across borders, and, more broadly, throughout that region of the world.

Turkey

Levent Çalıkoğlu is an art critic in Turkey who engages with contemporary art practices. Çalıkoğlu might view text art, like other critics in this paper, as a way to explore the relationships between language, culture, and identity. He might also see text-based art as a means of affirmatively challenging the power dynamics of languages themselves, and as a way to create new visual-symbolic modes of communication. Like others, Çalıkoğlu might also appreciate the ways in which text-based art can be used to create ambiguous and layered meanings, to afford new interpretations of complex political and cultural issues in Turkey.

Saudi Arabia

Ahmed Mater, the Saudi artist, writer, and art critic, who is known for his engagement with contemporary art practices on each of these levels, might see art with words and language as a way not just to explore the intersections of religion, culture, and identities in Saudi Arabia, but also of demonstrating and challenging the entrenched power dynamics of languages themselves.

Syria

Murtaza Vali is a Syrian art critic who writes on contemporary art practices in the Middle East. Like many others discussed in this paper, Vali might see text-based art as a means of considering how language, culture, and identity interact. He might particularly see text-based art as offering a medium to investigate traditional notions of Syrian art and culture relative to more contemporary views and voices. And like many other critics discussed here, Vali might appreciate that text-based art can be used by artists to create new forms of aesthetic expression that engage complex political and social issues within a country.

North America

Canada

Sarah Milroy is a Canadian art critic who writes about contemporary Canadian art. Like many discussed here, she might see text-based art as an aesthetic for exploring human intersections in her country, including how Canada’s multiple histories, languages, and identities interact. She might particularly view art with words and language as engaging with Canada’s histories with respect to cultures, including with respect to Indigenous peoples, that exist across Canada’s vast geographical space.

Cuba

Tamara Diaz Bringas, as both a Cuban art curator and as an art critic, might see text-based art as a way to engage with the political and social realities of contemporary Cuba. She might also see the potential for text-based art to address issues such as censorship, surveillance, and political repression, as well as to celebrate resilience and creativity in Cuban culture. She might also see the use of text in art as a way to connect with the history of literary expression, and all artistic expression, in Cuba.

Mexico

The art historian and art critic Raquel Tibol, who was born in Argentina and who died in Mexico City, and who wrote on Mexican and Latin American art, with a focus on social and political issues, might have seen text-based art as affording artists the possibility of engaging in new ways with issues of cultural identity and issues of national politics, using language to expressly critique dominant ideologies in order to encourage actions towards social change. Tibol might have been most interested in text artists who use language as a means of expressly engaging with specific cultural and historical contexts, such as some of the muralists of the 1920s and 1930s who employed text and language, including at times Diego Rivera, as well as artists who used language to challenge false narratives and assumptions supporting dominant norms of colonialism and imperialism.

The Mexican writer, poet, diplomat, and cultural critic Octavio Paz, whose writings included analyses on the intersections of Mexican art, literature, and politics, might have seen text-based art as allowing a wide range of artists to explore nuances of the most complex aspects of language, identity, and power. He might have been interested in artists who use text and language to not just document and but also call attention to marginalization and exploitation, as well as artists who employ language as a means of reclaiming cultural heritages, such as muralists of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Mexican muralist and painter Jose Clemente Orozco, known for politically charged artworks addressing social and political issues in Mexico and beyond, might see text-based art as a direct vehicle allowing artists and viewers alike to engage these issues, with word art enabling new uses and interpretations of language for the purpose of critique and subversion. He might be interested in artists who use text in a bold and provocative manner in the context of political, social, and cultural issues and assumptions, such the American text-based artist Barbara Kruger, whose large-scale installations and text-imagery works question power dynamics and artificial constructions in contemporary society relating to identity, sexuality, and consumerism.

The Mexican art critic and curator Marta Elena Bravo, who has written on contemporary art in Mexico and Latin America, might see text-based art as directly engaging with concepts of cultural identities and political power, using language both to critique dominant narratives and to offer new interpretations for social change. She might find of interest artists who use text as a means of exploring the full complexities of Mexican and Latin American cultures, such as the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco, whose works sometimes employ text with cultural artifacts to address not just identity, migration, and globalization, but also to blur ideas of the boundaries of art itself.

United States

Rosalind Krauss, the American art critic, art theorist, and professor at Columbia University in New York, and a leading figure in the field of modern and contemporary art theory, had an analytic approach that emphasized both the ideas of French post-structuralist thinkers, like Jacques Derrida, discussed below, as well as the importance of the role of the viewer in the interpretation and meaning-making of art. In her theory of analysis, a work of art is not fixed or determined exclusively by the intentions of the artist alone, but rather is also constructed through and by the viewer's interaction with the work.

In terms of aesthetics, Krauss might be interested in the ways that text-based art expressly challenges traditional notions of visual art (in all forms, including both figurative and abstract) and expands the theoretical and concrete possibilities of what art itself can be. She would likely emphasize the importance of considering the formal qualities of text-based art, such as work’s use of typography, materials, and composition, in addition to its substantive content.

In terms of a theoretical perspective, Krauss might be most interested in the ways that text-based art intersects with language and literature, and how it engages with issues of meaning itself, and also the nature of communication itself. She might draw on these to explore the ways that—and reasons why—language is inherently unstable and subject to multiple interpretations.

In terms of possibilities, Krauss might be interested in the ways that text-based art can be used to explore an unusually wide range of subjects and themes, from political and social commentary to personal expression, human feelings, and human emotions and intuitions. She might likely see text-based art as both a theoretically and practically valuable form of artistic expression that challenges traditional boundaries between art forms—and also successfully invites viewers to actively engage both with and in the meaning-making of text-based work.

Separately, the American art critic Jerry Saltz has written that he sees text-based art has having a robust history that stretches back to the earliest known examples of human expression. He might note that from ancient cuneiform tablets to modern-day graffiti, text has always played a vital role visual arts across mediums. He might say that, while there is a risk that text-based art can be didactic, or prone to teach, declare, or explain, rather than allowing for interpretation, what sets text-based art apart from other aesthetics is its ability to convey complex ideas and emotions through language and hybrids of language and image, as well as its potential to engage the viewer on both a visual and intellectual level through ambiguity and interpretation. Saltz might also write that text-based art offers a unique opportunity for artists and viewers to explore the intersections between language and image, and to push the boundaries of what a given society or culture considers to be art.

Given some of his writings, Saltz might argue that with the rise of both digital media and the beginning of the democratization of the art world, text-based art has become an increasingly important form of diverse visual expression, and one that has the potential to challenge our assumptions about who makes art, what art is, and what it can do both as an art form and as an element giving voice in unique ways in broader society.

Separately, the American art critic, poet, and educator Peter Schjeldahl might focus the risks of text-based art limitations while also seeing its possibilities. Specifically, he at times wrote that some text-based artists might lapse into the limitations inherent in all language forms, in that, depending on how approached, language-based art can be difficult for a viewer to engage with if it becomes didactic, or narrowly focused on teaching, telling, explaining, or otherwise becoming declarative. He has also written that text-based art can lapse into being overly intellectual, at least to his critical tastes, by prioritizing a substantive message over the viewer’s aesthetic experience with a work. He has also noted in his writings that text-based art for some viewers can be difficult to read or interpret, particularly where there are barriers across languages or references.

With the above risks and potential limitations in mind, Schjeldahl has also written that the promise and possibilities of text-based art exist at their fullest where an artist uses a given language and the forms of letters, characters, symbols, and words not just for expression of concrete subjects and themes, like social justice or specific political commentary, but also for reflexive questions looking inwards and introspectively on issues relevant to art itself, and language itself, including questions such as (1) what are the boundaries of visual art and language in relation to meaning; (2) where are the lines between didactic declarations and ambiguities that invite viewer interpretation; and (3) whether there are overlapping spaces in text-based art that are not just intellectually engaging but also emotionally and even spiritually engaging, even across borders and language differences.

Russia

The Russian art critic Boris Groys, who has written on the relationship between art and politics, might note some of the same theoretical points raised by Krauss, Saltz, and Schjeldahl, particularly as to the risk of text-based art resulting in works that are didactic, but given some of his writings he might still see text-based art as a powerful concrete artistic tool for political commentary and activism. His writings suggest a focus on art with words as having a unique ability to convey messages and ideas in a direct and impactful way as to both a particular viewer and as to a culture or society as a whole. Groy would likely observe text-based art as having potential because of its history, in that text, or text concepts, have played a lasting role in the development of art from the earliest symbolic cave paintings and rock etchings to the present day. He might also see the use of text in visual art as allowing for a range of artistic and aesthetic approaches, from straightforward communication without deeper meanings to more abstract and ambiguous messaging not just as to facts or views but also emotions and feelings.

Groy’s writings suggest that he would see text-based art as being able to incorporate other forms of media, such as video or sound, to create an immersive experience for the viewer using multiple senses and multiple parts of the brain, including the intuitive and the logical, particularly as new technologies emerge allowing artists using text to continue to push and blur the boundaries between art mediums, causing text-based art to remain a profound component of broader collective notions of art.

Aleksandr Benois was a Russian art critic who might have viewed text-based art as a unique way to express not just the concrete and the material but also, particularly, the spiritual and emotional dimensions of humanity and of art itself. He might see text-based art as a means to most clearly convey to the viewer the inner world of the artist, and the way to most clearly capture and share the essence of human experiences and ideas. Based on his writings, it appears that, for Benois, text-based art would be a way to bridge the assumed divide in some thought systems between the external world of objects, things, and reason, on the one hand, and the internal world of emotions, feelings, and intuition, on the other hand.

South America

Argentina

The Argentine art critic Marta Bravo might see the possibilities of text-based art in relation to the medium’s ability to explore and communicate ideas relating to political and cultural implications of dominant societal norms. She might view artists using text as being able to find a way to communicate social and political commentary through hybrid language-visual means, allowing an artist who uses text and image to more fully and more directly challenge oppressive political and social structures, both through the mind as well as through the heart, and additionally to serve as catalysts for potential social and political changes in the context of cultures and their histories.

Peru

Juan Acha, the Peruvian art critic, might see text-based art as a means of more robustly engaging with issues of identity and cultural heritage. He might view text-based art as a way of successfully exploring the intersections between language, culture, and history, and he might be interested in the questions of how and why text-based art can reflect upon, mirror, and critique specific cultural contexts, while also pushing boundaries and subverting expectations, in a way that engages the viewer by exploring ambiguities and encouraging interpretations.

South Asia

Pakistan

Quddus Mirza is a Pakistani art critic who has written on contemporary art practices in Pakistan as well as South Asia. Mirza might view text-based art as an art form and as a medium that provides a means of exploring the relationships between languages, cultures, and identities in Pakistan and its society. As with critics discussed above, he might see text-based art as a way for artists to challenge not just contemporary societal norms in Pakistan but also traditional notions of Pakistani art and culture, as well as to create spaces for marginalized voices in Pakistan in relation to Pakistan itself as well as to both elsewhere in South Asia and the broader world.

South Eastern Europe

Greece

Maria Marangou is a Greek art critic who has written on contemporary art practices in Greece as well as Western Europe, and might see text-based art in many of the same ways as other critics discussed above, including as a means of exploring the intersections of language, culture, and identity in Greece both now and historically. And like other critics discussed above, her writings suggest that she might see text-based art as a way to examine and evaluate traditional notions of Greek art and culture relative to contemporary, modern, and possibly also post-modern views.

Western Europe

France

Jacques Derrida, referenced above in the discussion of the American art critic, theorist, and academic Rosalind Krauss, is the prominent French philosopher and literary critic across multiple disciplines who made watershed contributions to Western philosophy as the conceptual founder of deconstructionism. Very broadly, for purposes of this short monograph / artist’s studio paper, deconstruction is an analytic useful for criticizing not only literary texts and philosophical texts, but also societal and political constructs, in an attempt to find or create concepts of justice in those texts and constructs.

Applied here, through the analytic of deconstruction, Derrida might see text-based art as a profound vehicle by which to questions the very idea of meaning itself, a question transcending any one language or any one aesthetic, and approaching questions of the universal. More specifically, he might especially see text-based art as being able to highlight and explore all of the multiple and often contradictory interpretations that can be read from, and applied to, almost any given textual or language-based statement, be it as short as a single phrase or as long and complex as an entire novel—and by extension, almost any given idea or view that may be expressed in those texts.

As the founder of deconstructionism in all its applications, Derrida would likely be most interested in text artists who are most adept at avoiding the didactic and declarative, and rather are able to experiment with ambiguity, multiple interpretations, and viewer interaction for meaning-making to its fullest, and thereby challenging traditional modes of artistic expression that focus only on the intent of the artist, and not the participation of the viewer in the act of interpretation. As such, Derrida might see the influential American text-based artist Jenny Holzer as at the vanguard of the possibilities of text-based art, given that Holzer’s public space installations worldwide, both large and small, offer viewers intentionally ambiguous phrases and sentences that are not just open to multiple readings, but which also invite those multiple readings in some of the most profound areas of human thinking, interactions, and questions of morality and ethics.

The French literary critic and philosopher Roland Barthes, who has written on semiotics, the study of anything that can make meaning through any of the human senses, has, relevant here, written on the relationship between semiotics, language, and culture. He might see text-based art as a means of exploring the cultural and political significance of language in making meanings, and also exploring how and why those meanings might be interpreted by different recipients the same way or different ways. Also relevant here, many of his writings appear to emphasize the possibility of, and the intellectual utility of, the ability for text-based art to create multiple meanings, ambiguities, and interpretations, even the simplest of texts, including even short phrases, one word, or even a character-symbol—or even a sound of a word or a letter. Loosely from his writings, Barthes would arguably see the most meaningful of text-based artworks as those being made by artists who experiment with language in a self-reflexive manner, inwardly and introspectively, using language to question the very nature and qualities and possibilities of language itself, such as the influential American text-based artist Lawrence Weiner, particularly as to his text works that provide written instructions to viewers on how to create a specific piece of art as an theoretical exercise and experiment in the exploration of language itself and, the ability of language structures to make, record, and transmit meanings to recipients.

Germany

Erwin Panofsky, the German-Jewish art historian, who wrote about the modern study of iconography, the Renaissance, and meaning in the visual arts, including the 1955 book “Meaning in the Visual Arts,” might have used his three strata for evaluating subject matter or meaning of text-based art. For Panofsky, his process was to look at and consider (1) the primary or natural subject matter—what we see at first; then (2) the secondary or conventional subject matter—the meaning of what we are seeing, including its references; and then (3) the tertiary or intrinsic meaning or content—such as, why did the artist decide to create the art in just this way, and what are other signals as to complete meaning? Panofsky might consider this third level, or third strata, to be most important in text-based art, because it might allow the viewer to look at text based art not as an isolated movement in art, but as the product of the environment in which is developed in a particular place over time and history—in order to answer the ultimate questions, for a piece of art, including for a piece of text-based art, of what it all means—and, most importantly, echoing Rosalind Krauss, what are all the possible things that it could mean when the viewer completes the work?

Italy

Achille Bonito Oliva is an Italian art critic known for his engagement with contemporary art practices in both Italy and Western Europe. Like many of the critics discussed above, Oliva might view text-based art as a means of exploring the relationships and interactions between human languages, cultures, and identities of peoples in Italy and in surrounding countries in Europe and the Mediterranean region. He might also see text-based art as a way to challenge deeply-rooted traditional notions of Italian art and culture, and to juxtapose them against contemporary Italian norms, and Western norms, in cultures and societies.

Conclusions of Part 1

To be clear, these overviews are only short summaries of just a few of the writings, theories, and criticisms of these art critics, curators, art theorists, art scholars, and artist-critics, who in turn are just a few of the experts and thinkers in these areas and fields worldwide. That said, based on research of them so far, my tentative conclusions about global text-based art include that—despite often fundamental and even acute differences in philosophical systems, thinking systems, religious influences, and political, economic, and social structures and assumptions, text-based art is (a) evidenced as an art form almost everywhere on the planet for (b) many of the same philosophical, artistic, and concrete reasons.

Broadly speaking, those reasons appear to be that text-based art—loosely and broadly defined here as any visual art that uses words, language, characters, or language-symbols in some way—affords artists, no matter where they are globally, across continents, countries, and cultures, an artistic aesthetic and a means of artistic expression that can address, explore, and wonder about:

· Our most concrete and present issues and needs;

· Our most abstract and philosophical questions about the intellectual head and the emotional heart;

· Our questions about our languages themselves; and

· Our questions about art itself, including, what is art?

I think text-based art can be beyond cool—and way beyond deep. It’s because I think a piece of text-based art, and a long-term body of text-based work, can be all of these things, cumulatively, cohesively, even sometimes all at once. This is what I think, and what I feel, when I say, this is text-based art.

Part 2 to follow.

About the Creator

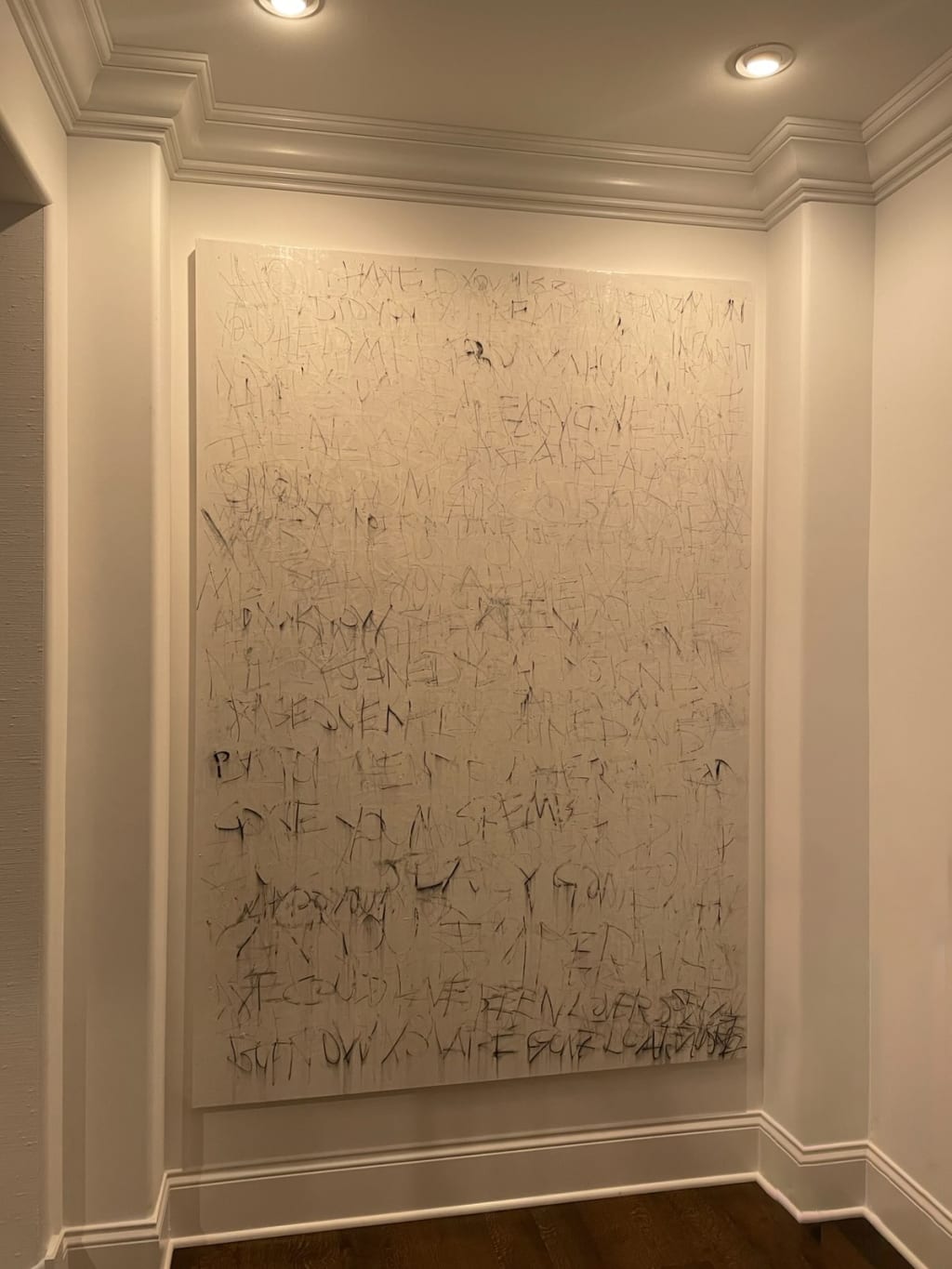

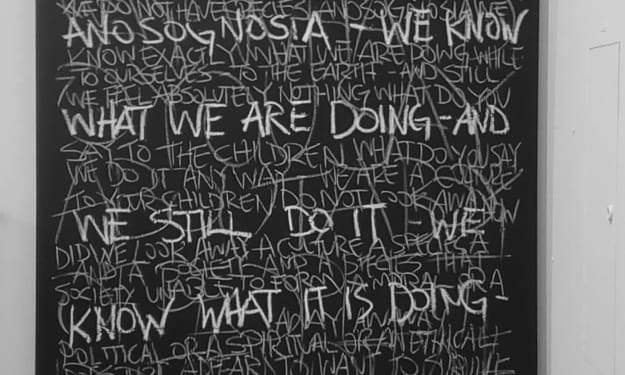

Adam Daley Wilson - Conceptual Artist + Appellate Lawyer

Adam Daley Wilson is an American conceptual artist and painter represented by Engage Projects Gallery Chicago. He is also an appellate lawyer from Stanford Law who briefs issues from artist's rights to the First Amendment. Portland, Maine.

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insights

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments