The Hidden Language of Frida Kahlo: Symbolism, Pain, and Power

What Frida’s Art Really Means (And Why It Still Hurts So Good)

Frida Kahlo didn’t just paint pictures. She painted pain, politics, passion — and every stroke was a cry from the soul. Her self-portraits are among the most emotionally raw and visually iconic works in 20th-century art. But beyond the bold eyebrows and surreal backdrops, Kahlo embedded coded messages that speak volumes about identity, feminism, colonialism, and resilience.

This isn’t just self-expression. It’s self-mythology.

I. The Self as Sacred Territory

Kahlo painted herself more than 50 times — often because she was physically isolated for long periods due to her lifelong medical issues. But these weren’t just vanity portraits. She once said, “I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.”

Yet the subject wasn’t just “Frida.” It was what Frida meant — as a woman, as Mexican, as broken, as defiant.

II. Decoding the Symbols

Let’s break down just a few:

1. “The Two Fridas” (1939)

Two versions of Kahlo sit side by side: one in traditional Tehuana dress (her heritage), the other in European attire. One heart is torn open. The other is whole. Between them, a vein connects and bleeds.

This painting came after her divorce from Diego Rivera. But it’s more than heartbreak. It’s a metaphor for cultural duality, internal conflict, and the violence of colonial erasure.

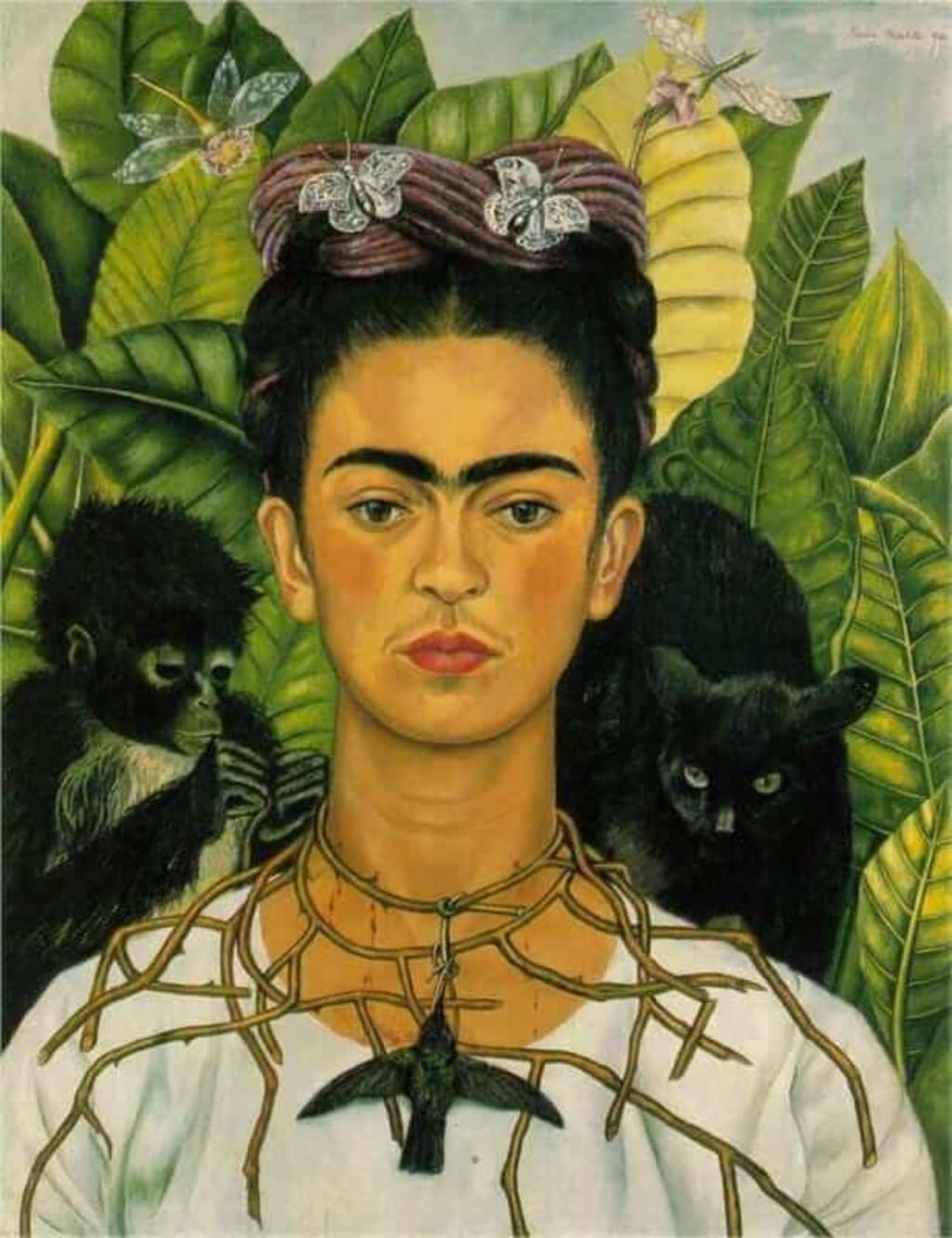

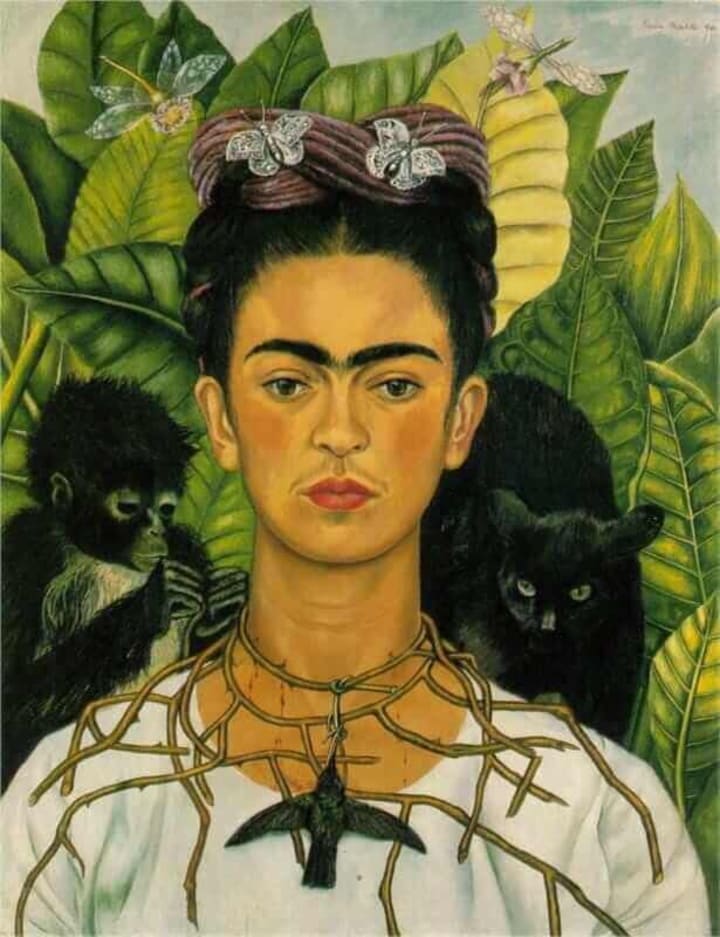

2. “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” (1940)

A black monkey (often symbolizing Diego) tugs her thorn necklace, drawing blood. A dead hummingbird — traditionally a symbol of hope or love — hangs like a pendant. Surrounding her: jungle leaves, butterflies, a black cat.

It’s a battle between life and death, passion and pain — all on a face that remains calm, staring straight into the viewer.

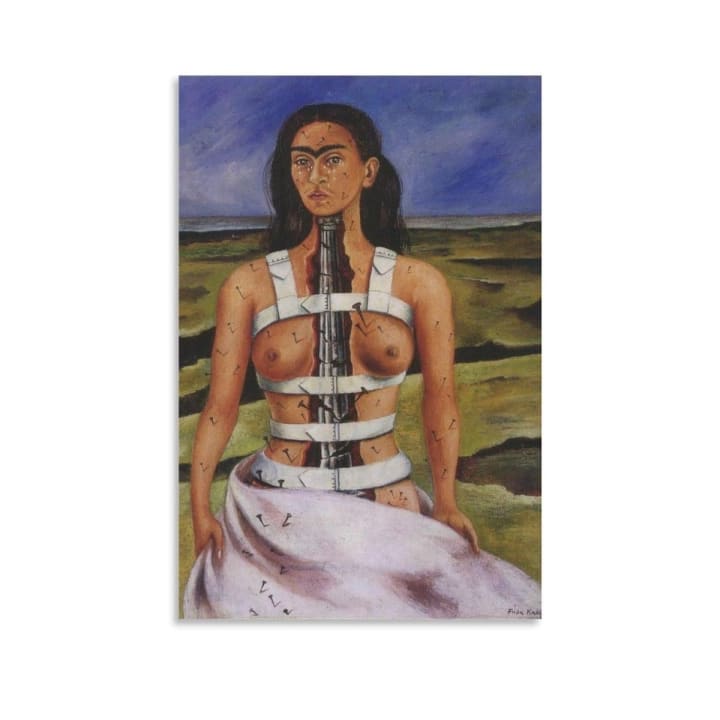

3. “Broken Column” (1944)

Here, Kahlo’s torso is split open, replaced with a crumbling ionic column. Her skin is pierced with nails. Tears stream down her face.

After yet another spinal surgery, this image is both literal and mythic — pain turned into architecture. She becomes a ruin, and in doing so, she also becomes a temple.

III. Frida and Feminism (Before It Had a Name)

Frida Kahlo never used the word “feminist.” But her work is steeped in it. She painted female suffering not as something to pity, but as something sacred, powerful, worthy of rage and reverence. She made her unibrow iconic. She portrayed miscarriage and menstruation. She refused to make herself small, even when broken.

And she dared to say: this pain is mine, and I will make it beautiful.

IV. Why Frida Still Feels So Relevant

In an age of curated identities, Kahlo reminds us that self-representation can be both radical and vulnerable. Her work wasn’t made for Instagram — but it thrives there — because it’s truth. Unfiltered, stylized, painful truth. And it’s addictive.

Conclusion:

Frida Kahlo’s art isn’t easy. It’s not meant to be. It’s meant to wound, to whisper, to warn — and above all, to witness. Through blood, vines, broken spines, and burning hearts, Kahlo created a language only the soul understands.

We don’t just look at her portraits. We feel them.

About the Creator

Zohre Hoseini

Freelance writer specializing in art analysis & design. Decoding the stories behind masterpieces & trends. Available for commissions.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.