The Birth of Venus: Botticelli’s Pagan Protest in Christian Florence

Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus”: Beauty, Power, and Pagan Rebellion in a Christian World

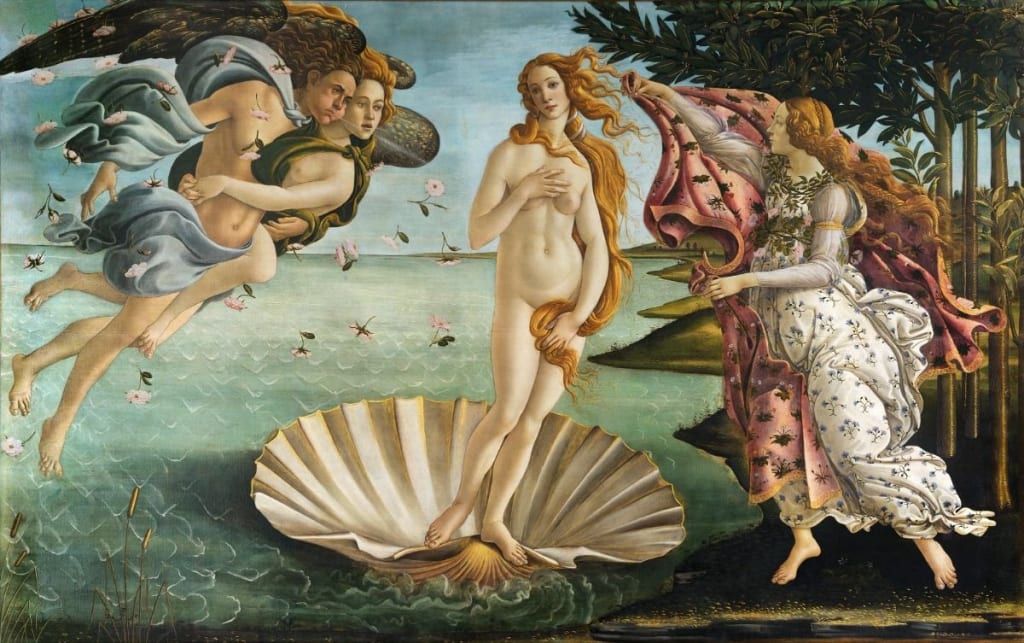

At first glance, The Birth of Venus is all softness and grace—an ethereal goddess standing on a shell, welcomed ashore by the winds and a waiting figure with a floral cloak. But look deeper, and Botticelli’s masterpiece reveals itself not as a sweet mythological fantasy, but a daring act of artistic rebellion cloaked in beauty.

Created in a time of religious authority, The Birth of Venus whispers of ancient philosophy, forbidden ideas, and a radical message: that beauty is sacred, sensuality is divine, and the human spirit deserves worship.

The Goddess Returns

Painted around 1484–1486, The Birth of Venus was commissioned by the Medici family—wealthy patrons of the arts and often silent challengers of Church power. In a deeply Christian world, Botticelli dared to place a nude pagan goddess front and center. Why?

Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, was more than a symbol of desire. Through the lens of Neoplatonic philosophy—a revival of ancient Greek thought—Venus represented divine love, the bridge between earthly pleasure and spiritual enlightenment.

To the initiated, this wasn’t a painting of lust. It was an invitation to contemplate the higher self through beauty.

The Shell: Symbol of Transformation

Venus’s arrival on a scallop shell may seem decorative, but it’s loaded with symbolism. In ancient cultures, the shell represented birth, fertility, and transformation. It echoes baptism—a cleansing, a rebirth. Botticelli wasn’t just painting a goddess; he was painting the awakening of the soul.

Some scholars believe Venus’s arrival is a metaphor for the rise of beauty and wisdom into a world of chaos—an echo of humanism’s ideals rising amid medieval rigidity.

The Winds and the Cloak: Forces of Nature and Virtue

To Venus’s left, Zephyrus (the west wind) embraces Chloris as they blow her ashore. This isn’t just myth—it’s metaphor. Zephyrus symbolizes the force of nature, and Chloris (later Flora) represents blooming life. Together, they guide Venus—beauty—into the world.

To her right, the Hora of Spring waits with a floral robe. Her gesture isn’t modesty, but celebration: beauty is worthy of welcome, not shame. It’s a visual rejection of the era’s tendency to hide the body under the weight of sin.

A Nude in a Christian World

Botticelli painted this nude not with sensuality, but serenity. Venus doesn’t seduce; she stares past us, calm and removed. There’s no shame in her exposure. In fact, her posture mirrors ancient statues of Venus Pudica, a gesture of modesty—but also self-awareness.

In a culture where the Church condemned nudity, this was radical. Botticelli wasn’t hiding rebellion—he was decorating it with grace.

Was Botticelli Himself Torn?

Later in life, Botticelli fell under the influence of Savonarola, a Dominican friar who denounced paganism, art, and vanity. Rumors suggest Botticelli even burned some of his own works in the infamous Bonfire of the Vanities.

This spiritual conflict adds a haunting layer: The Birth of Venus could represent the last breath of classical freedom before the artist was consumed by religious fear.

Why It Matters Today

In our world of filters, fast judgments, and cultural debates, The Birth of Venus stands as a timeless statement: that beauty isn’t shameful, that wisdom can bloom through ancient roots, and that the human body—far from being a sin—is a spark of the divine.

Botticelli didn’t just paint a goddess. He painted a question:

What if beauty is truth?

About the Creator

Zohre Hoseini

Freelance writer specializing in art analysis & design. Decoding the stories behind masterpieces & trends. Available for commissions.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.