Profit, Plunder, and the Proletariat

"The Threepenny Opera" on Stage & Screen

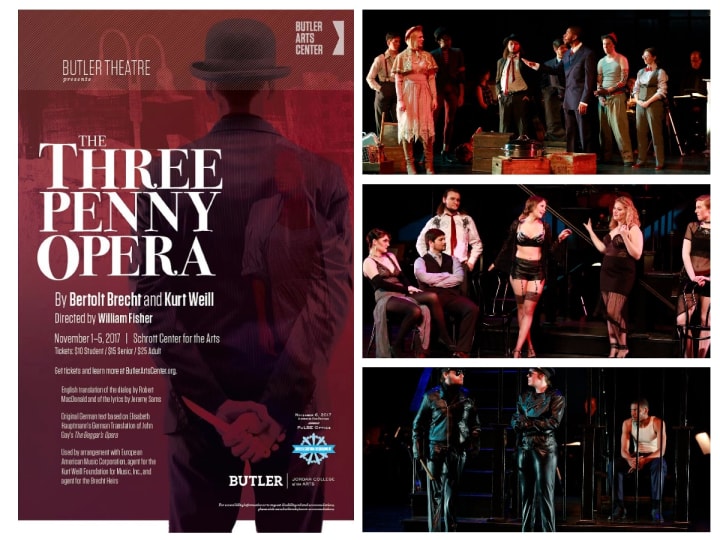

The Threepenny Opera stands as one of the most scathing indictments of society ever to grace the stage. It is a darkly satirical masterpiece (one I had the opprotunity to perform in as a college theatre student), that strips away the exterior image of respectability to reveal an interior world; one where morality is for sale to the highest bidder. Born from the collaboration of playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer Kurt Weill in 1928, the work blurs the boundaries between high art and popular culture. Together they weaved together biting social critiques and revolutionary theatrical techniques. When their landmark production was first put to the silver screen, in 1931, the narrative became infused with a cinematic realism that further exposed the rot at the core of societal norms and contemporary human behavior. This analysis explores the historical background of The Threepenny Opera, while also examining how the stage play’s revolutionary approach to theater evolved in the new medium of cinema; as well as how future adaptations continue to resonate as powerful commentaries on pervasive social corruption.

Although Brecht and Weill have almost become a trademark for the music and performing arts scene (created during the era of Germany's Weimar Republic), in cultural retrospect, their names are almost as synonymous as Gilbert and Sullivan; or even Rodgers and Hammerstein. Yet, behind the veneer of successful artistic partnership, their relationship was extremely fragmented and tumultuous. As it lasted only four years, when they were collaborating on project after project. Brecht was almost by textbook definition, an idealistic vagabond. He ran around in tarnished clothes, underneath a military-grade leather jacket; trying to be a counterculturist in the social circles of Berlin, following the end of World War One. In terms of his personality, he was very strong-willed. In discussions with other people, he would go in with the mindset of how his position must win out, every time; feeling as though very few rules in life applied to him. Romantically, he was very promiscuous, and (furthermore) in terms of day to day living, had no real sense of "home". Compared to Kurt Weill, a much more sophisticated, regimented, and artistically disciplined man, one would never expect these polar opposites to attach their names and reputations together, in the world of show business. Yet, that's almost exactly what happened, historically.

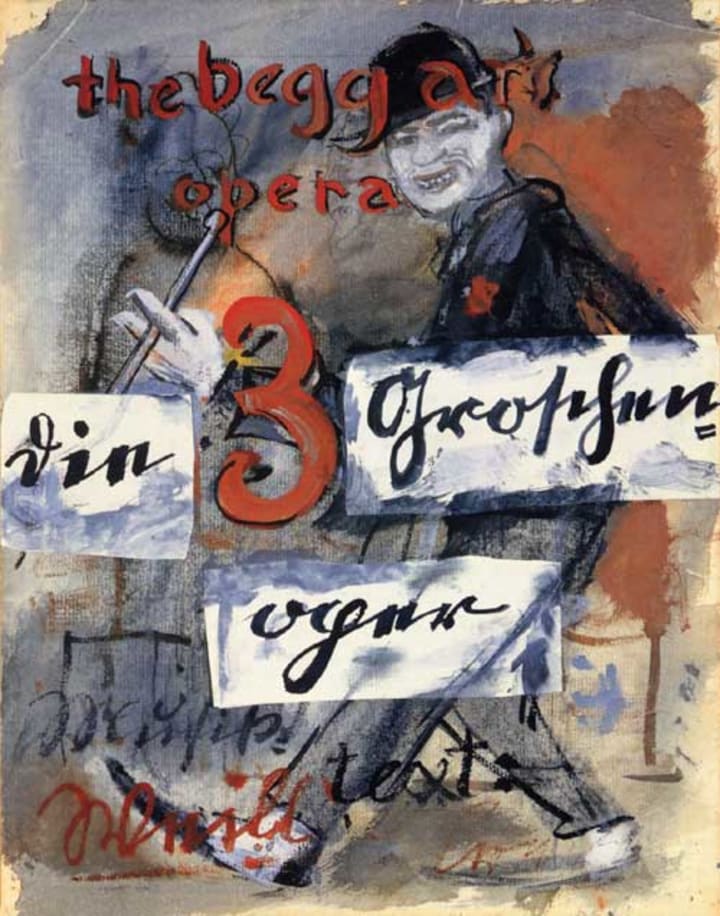

In 1920, there had been a successful revival of John Gay's 1728 opera, The Beggar's Opera. Originally, a satirical work designed to lampoon the British aristocracy. Bertolt Brecht's secretary and girlfriend, Elisabeth Hauptmann, heard of this revival, and her knowledge of English allowed her to make a translation into German. Brecht used her literal translation as the basis to re-work the 18th century opera into a work that much more culturally relevant; not only in terms of its physical imagery, but also its thematics and narrative elements. He changed the story substantially, added new songs, and incorporated new characters; making the story his own. Prior to this work, Brecht had only begun his career as a playwright following his conscripted military service in World War One. Many of his early plays are considered to be extremely expressionistic and nihilistic. These plays included Baal, Drums in the Night, In the Jungle of Cities, and Man Equals Man (which had Peter Lorre in his first leading role).

Written between 1918 and 1926, these dark plays featured angry and disillusioned young men as protagonists. Yet, these characters were ultimately lacking any real political points of view. Yet, it was in 1927, when Brecht's play Mann ist Mann (Man Equals Man) was recited over the German radio. At that time, Kurt Weill was earning his living as a critic; writing reviews of radio broadcasts for a weekly newspaper column. In his review of this radio play, he declared that Brecht's work had become the drama and poety of their time. Following the broadcast, Weill acquired a published collection of Brecht's poetry, called Hauspostille; roughly translated to Home Devotions in English. Inside this collection, Weill discovered a poem, written entirely in English, and was entitled The Alabama Song. He would later receive permission from Brecht to use this poem for the composition of a one-act opera in Baden-Baden, called Mahagonny, ein Songspiel.

With Brecht the poet, and Weill the classical composer together, they would become known in the eyes of the general public, through Brecht's recent reworking of The Beggar's Opera; called Die Dreigroschenoper (or The Threepenny Opera) in 1928. The musical's story unfolds in the grimy, bustling streets of Victorian London, where the lines between respectability and criminality blur. At its heart is Macheath, better known as "Mack the Knife," a charming yet ruthless gangster whose influence stretches across the city's underworld. Beginning with Macheath’s clandestine marriage to Polly Peachum, the naive daughter of Jonathan Jeremiah Peachum; a calculating and merciless businessman who controls London’s beggars through a network of manipulation and fear. Outraged by his daughter’s union with a notorious criminal, Peachum vows to ruin Macheath, by pressuring the corrupt Chief of Police, and Macheath's old army buddy, Jack "Tiger" Brown, into betraying their longstanding friendship and arresting him.

Meanwhile, Polly, eager to prove herself to her new husband, steps up to manage Macheath's criminal empire in his absence, revealing unexpected cunning and strength. As the net closes around Macheath, he seeks refuge in the city's brothels, where he encounters Jenny Diver; a prostitute with whom he shares a complicated history. Jenny, still nursing her old wounds, chooses to betray Macheath to the police in exchange for a reward. Captured and sentenced to death, Macheath faces execution, but the play takes a sharp, satirical turn. At the last moment, Macheath is miraculously pardoned by a royal messenger who arrives on horseback, delivering a reprieve from the Queen herself. Instead of execution, Macheath is granted a title, a castle, and a substantial pension, highlighting the absurdity and corruption of the societal structure.

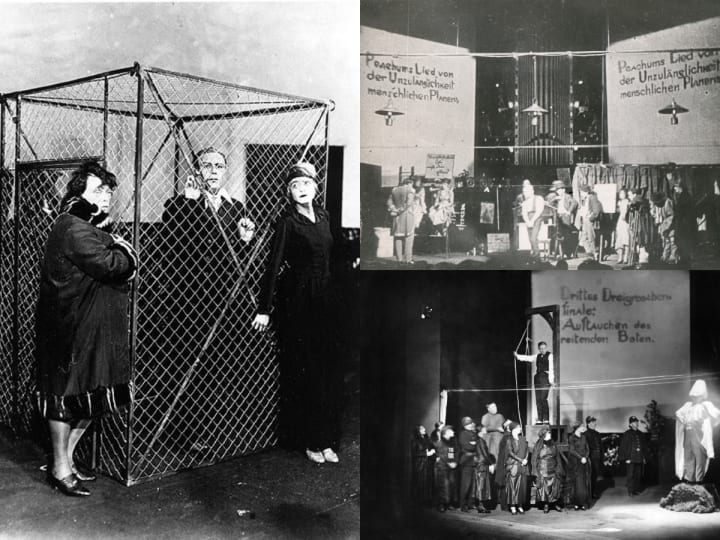

By the time the show premiered in August of that year, Brecht's writing was complete, and lyrical revisions were in place, but it was Weill who stepped in to infuse newly crafted music to give Brecht's written words new life; especially when you consider that many of the songs in the original John Gay opera were already variations of British folk songs, hymns, and opera arias. Weill's composition, in contrast to using an authentic classical orchestra that was unseen by the audience, beneath the stage, he would introduce the show with a modern jazz band, The Lewis Ruth band (7 musicians playing 22 different instruments), playing an 18th century style overture, on the stage; as the actors were performing the scenes. This would be followed by Mr. Peachum's Morning Anthem, one of the original songs from John Gay's opera. Nowadays, this isn't the case; because before the show premiered, the actor playing the protagonist, Macheath, requested an entry number. Brecht & Weill refused, but would later compromise on a prologue, sung by the street narrator, that chronicles all the notorious crimes committed by Macheath, entitled Die Moritat von Mackie Messer (The Ballad of Mack the Knife). This song has since become the most famous song in the show, thanks to its plethora of covers by the like of Louis Armstrong, the Muppets, and even McDonalds.

Along with this song, Weill would incorporate other forms of more contemporary music and dance idioms, such the Tango, the Foxtrot, the Charlston, and the Boston Waltz. These inclusions added to he popularity of the show. Even on opening night, the audience originally had no reaction to the play, until the Kanonensong (Cannon Song) was played; which required an immediate encore.

Even though the various crises occurred, as we call them "Murphy's Law" in today's time (actors falling ill, actors refusing to perform certain songs, etc.) the production became a hit; running in repertoire and in various international theaters, until it was outlawed in 1933. Yet, one can attribute the majority of the shiow's populatity to Kurt Weill, and the mionority to Bertolt Brecht. Nevertheless, one can also argue that without Weill's music, Brecht still has a fuctional play that could still work, with lyrics that could still be recited as "spoken word poetry" instead of sung. Though, iot woud've never been as popular as it became.

The collaboration of the two people together in musical theatre was something of a first in the German performing arts scene; but not without both men struggling over which element of the show was more important. Was it the music that overpowered the written words, or vice-versa? Certainly Weill's music does wash out the play's narrative, written by Brecht, but it also gives those words a unique feeling of catchiness and emotional tension. Such impressions that audiences still experience when attending a production of The Threepenny Opera. Personally, Weill sought to bring his compositions to newer forms and wider audicnes, beyond the traditional concernt hall (in an almost museum-like state). Certainly the theatre of the 1920's offered that opprotunity to him. Many attempts were being made to break out beyond the typical forms of naturalistic theatre; esptabloished by the likes of August Srindberg, Henrik Ibsen, and Anton Chekov in the mid to late 19th Century. More and more theatre productions began to experiment with new concepts, such as theatre in the round, cabaret, vaudeville, and "breaking the fourth wall". Methods that we consider a part of "Epic Theatre", to establish the idea that what's happening on stage isn't real life. This is the theatre and the audience knows it. An effect that Brecht would coin as "Verfremdungseffekt" or "Alienation Effect".

However, following the show's unexpected success, nobody knew what to do. Even Brecht himself. As early as 1927, he had become a student of Marxism, and following the popularity of the stage show, became embarassed; especially when the left-leaning newspapers declared that the play had "no socio-political impact, whatsoever". With his newly embraced philosophy, he sought to make The Threepenny Opera more "communistic"; first by publishing a novelized version in 1930, as well as being offered the opportunity to sell the rights of the musical to film producer Seymour Nebenzal, and director G. W. Pabst.

The 1931 film version of The Threepenny Opera is by many means a classic; as it serves as a powerful document of the Weimar era of Germany, and serves as a milestone in early 20th Century cinema (alongside the likes of Fritz Lang's Metropolis, and F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu). However, if one approaches this movie, thinking at they're going to see the original stage musical put to screen, that's only setting oneself up for dissapointment; and one will not grasp an understanding as to why the play stands as one of the most popular and pioneering works of theatre in the German language. The plot is changed, the narrative is emphasised very differently, many of the stage characters are removed, and half of the music is missing. This is because of a clash between Nebenzal, Pabst, and Brecht. A contract between the three men, implied that Brecht would write a script that would help translate the original 1928 stage show to film. Brecht deliberately violated the contract by giving Nebenzal & Pabst his own marxist revision of the story; transforming the character of Macheath from an underworld criminal kingpin, into a middle class character, in order to establish a poltical reflection between criminals and capitalists.

This revision and breaking of contract resulted in Nebenzal & Pabst secretly hiring on a Hungarian writer, Béla Balázs, to go back and create a hybrid version, with both elements from the original musical and Brecht's revision. Brecht's revision he gave, ended the story in a vision of class warfare between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Nebenzal, Pabst, and Balázs completley changed that for the final cut of the film. They ended the story with Macheath being saved from hanging, and with Polly Peachum forging the city bank; using Macheath, Jonathan Jeremaiah Peachum, and Tiger Brown as capital to keep the proletariat in line. Such an endeavor would later result in scandal and a lawsuit brought about by Brecht. A lawsuit that Brecht ultimatley lost in court, due to his breaking of the original contract. Even the communist critics who watched the film and reviewed it, complained that Brecht didn't know the proletariat when he saw them. In Brecht's mind, he perceived the rags and beggars people were the proletariat; not the working class.

Kurt Weill's sentiments were only slightly more positive than Brecht's. His main criticism was how the studio used only half of his music; as well as how the music that did make the final cut of the film was used out of order, and used inappropriatley (either as background instrumentals or sung by the wrong characters). The most well known example of this is the song "Seeräuber-Jenny" (or "Pirate Jenny"). On stage, the song is supposed to be sung during the wedding scene, in the beginning of Act One, by Polly Peachum; describing the prostitute Low Dive Jenny and her desire to free herself from the socially oppressive world of Victorian London, with a pirate ship and crew under her command.

However, in the Pabst film, that's completley changed. Lotte Lenya (who played Jenny in both versions) was given the task of singing "Pirate Jenny" in the brothel scene, near the end of the Act One. This rearrangement has since created a great sense of confusion for productions of The Threepenny Opera since then, with actors who are cast in the role (typically famous people), thinking that this song is their character's big show number. Lotte Lenya always insisted that wasn't to be so; saying that any production of the show which has Low Dive Jenny as a major role in the plot has something wrong with it from the get go.

When the film was released in February of 1931, it was nowhere near as successful as the original stage production. Whether or not the movie actually lost money at the box office remains unkown, but the dichotomy in terms of revenue made between the stage version and the screen version was about as far apart as Key West, Florida is to Barrow, Alaska. Some factors that may have played into this, may have been that by 1931, the scene in Germany was changing intensively. Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party were growing in political power, and the cyncially humorous attitude by theatre audiences in the 1920's was long gone. The Great Depression, brought about a real sense of fear of what's to come with a failing economy and the rise of extremism in the government. By 1933, both the play and the film were banned by the Nazis, and many copies of both were destroyed. Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya fled to the United States to continue their careers in New York, while Bertolt Brecht made his way across multiple European countries; continuing his work as a playwright until his death in 1956. The film would later be restored and reconstructed, following a 1963 remake of the Pabst film.

Furthermore, by the time Kurt Weill died in 1950, The Threepenny Opera was virtually unknown to audiences in the United States. The Pabst film did premiere at the Warner Bros. Theatre in 1931, in New York; followed by a production of the original play on Broadway, in 1933. It for ran only 12 performances, and the German aestetic of both versions made no sense to American viewers. Which resulted in negative reception. Following the end of World War II, in 1945, there was talk between Brecht and Weill reuniting for a Broadway revival of the show. However, neither of them agreed that the endeavor would be successful; given the cultural anti-German sentiment, in the U.S., at that time. It wouldn't be until 1952 when American composer Marc Blitzstein wrote a new translation of the play. It was performed as a concert version, conducted by Leonard Bernstein at the Brandeis University Creative Arts Festival in Massachusetts, to an audience of nearly 5,000 people; with Blitzstein as the narrator, and Lotte Lenya performing as Jenny. This would inspire an off-Broadway run of Blitzstein's version at the Theater de Lys in Greenwich Village, which ran for a total of 2,707 performances, as well as resulting in both a profitable soundtrack album and a Tony win for Lenya.

In the decades since the "Threepenny Renaissance" has this work gained a new lease on life, with a plethora of revivals and new translations on stage and screen internationally, with several celebrities donning the role of Macheath (from Raul Julia, to Sting, to Alan Cumming), and even a biopic about the making of the show; serving as the lasting power and cultural relevance of Brecht's words and Weill's composition, and one of the most compelling monuments of social banditry in the performing arts; posing the questions to each person who sees the show and listens to the song as to where the line is drawn between capital and criminality.

About the Creator

Jacob Herr

Born & raised in the American heartland, Jacob Herr graduated from Butler University with a dual degree in theatre & history. He is a rough, tumble, and humble artist, known to write about a little bit of everything.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.