Potchitra of Bengal: A Canvas of Tradition and Storytelling

The canvas of Bengal

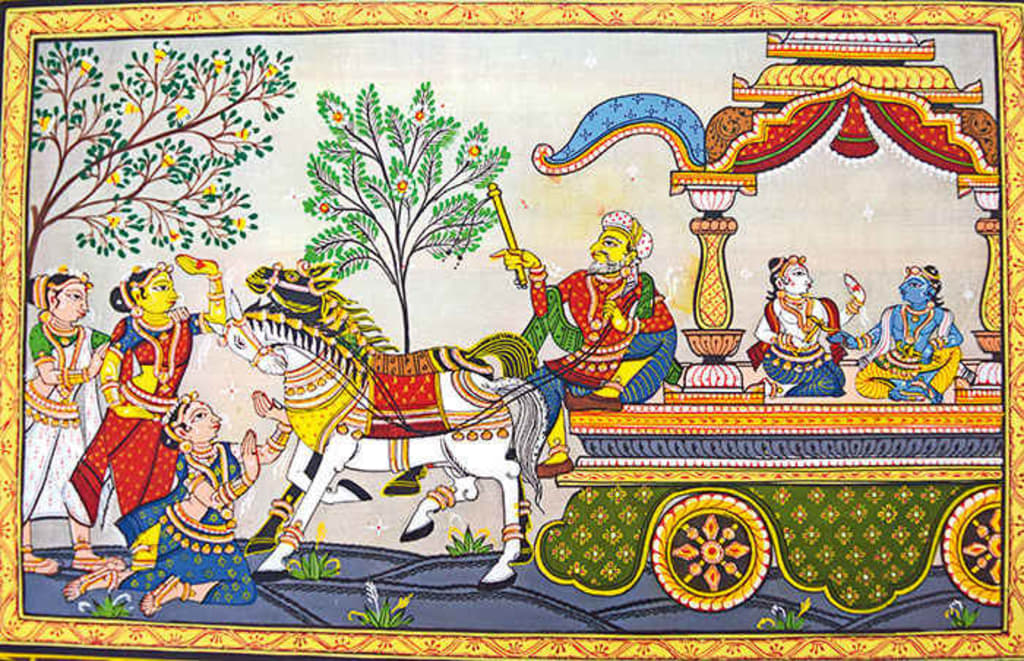

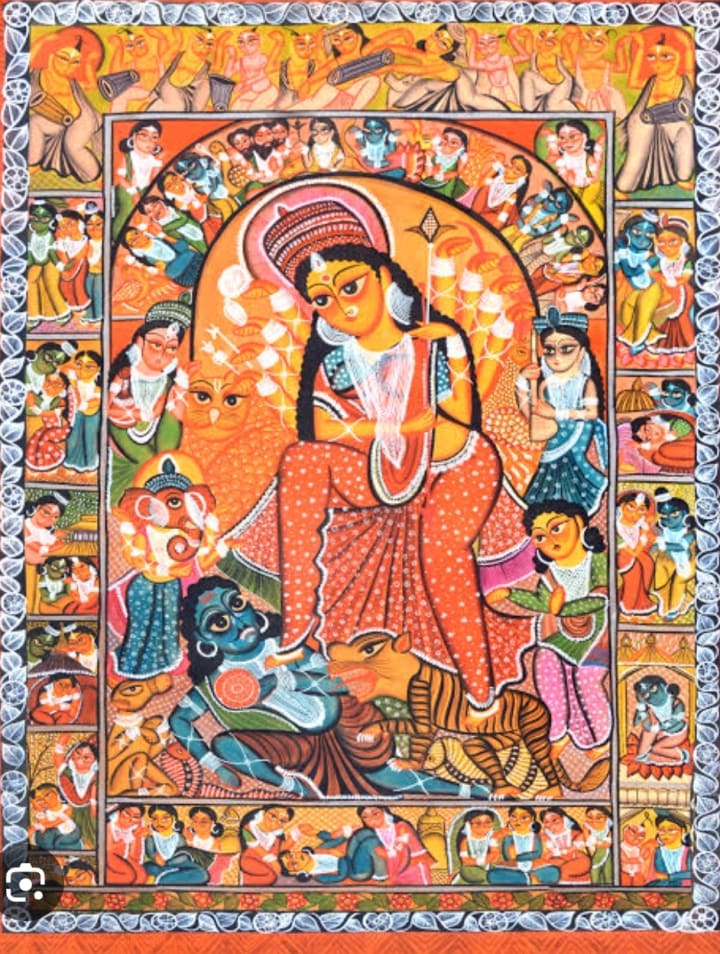

For over two and a half millennia, Potchitra has been intertwined with the soul of the Indian subcontinent — a canvas where myth, devotion, protest, and pedagogy dance in vibrant colors. More than mere decoration, it has served as sacred expression, an educational medium, and a mirror to societal change. This ancient form of art, deeply woven into the cultural fabric of Bengal, is not just painted — it is performed, sung, lived.

Across the breadth of Bengal, the scrolls of Potchitra unfold tales both divine and mortal. They echo spiritual yearnings, portray social realities, and once in a while, whisper revolutions. It was the visionary artist Dukhushyam Chitrakar of Naya village who dared to unroll a new path — boldly shifting from the traditional to the transformative.

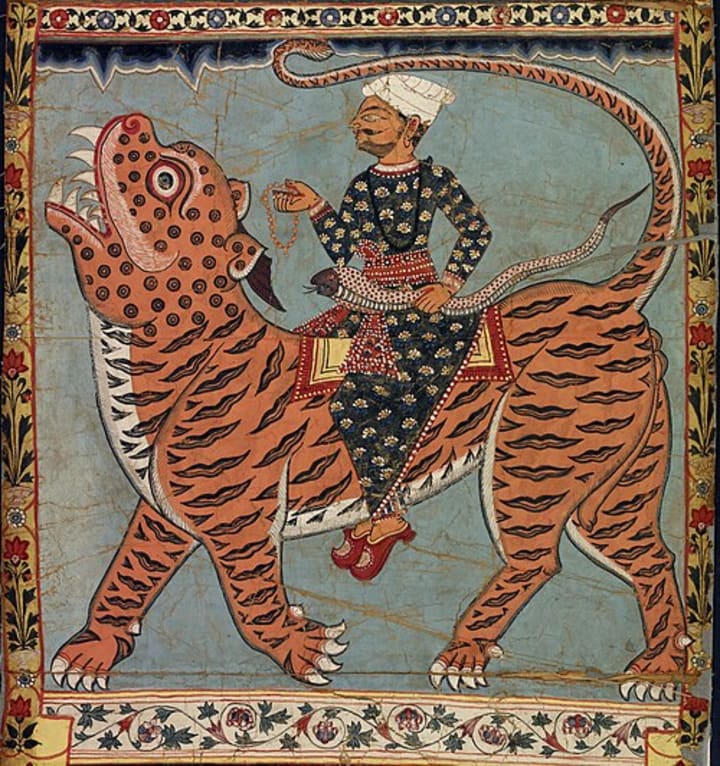

The word “Pot” finds root in the Sanskrit “Patta”, meaning cloth — the foundation upon which these vivid stories come alive. The canvas is not plain but prepared with layers of mud, dung, and glue, making it firm like the truth it intends to carry. With earth-born pigments — soot, vermillion, brick dust, turmeric, coal, and chalk — the artist begins to breathe life into stories. Each hue tells a tale. Each stroke echoes a belief.

But painting is only half the song. The Patua — the artist — is also a bard. Unfurling their scroll, they sing Poter Gaan, narrating the journey from gods to commoners, from heavens to the heart of rural life. Once, these performances were the soul of festivals and gatherings. In return, the Patuas received honor and sustenance — and the echo of applause etched in memory.

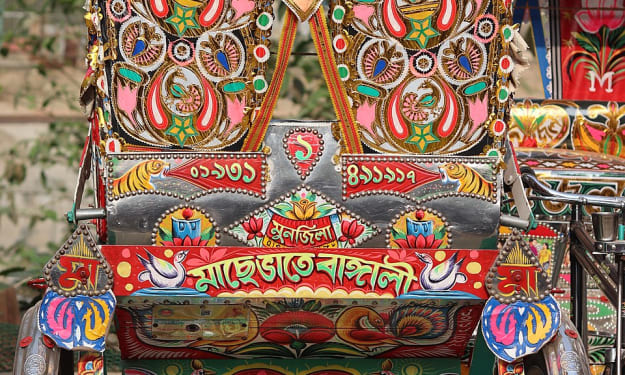

From the Rarh lands to Birbhum, from Midnapore’s plains to Murshidabad’s quiet lanes, Potchitra has traveled and thrived. Especially in Pingla’s Naya village, nearly fifty families continue to guard and grow this legacy — their brushes steeped in tradition, their songs rich with memory.

Yet times change. Today, many buyers seek satire over scripture — ‘Babu culture’ caricatures over divine scenes. Sales may rise, but with them, the echoes of ancient glory fade. The brush meets commerce, and tradition often bends.

Potchitra’s footsteps can be traced back to the 7th and 8th centuries. In Banabhatta’s Harshacharita, the emperor watches a Patua among children — perhaps history’s earliest recorded art class. Mentions flicker in Kalidasa’s plays, in the writings of Bhavabhuti, and even in Buddhist and Hindu scriptures. Some believe Bengal’s Patuas descend from the painters of the Buddhist era. The art, then, is as much a spiritual heirloom as it is a visual one.

The Gazi Kalu scrolls — inspired by Islamic lore — stand as luminous proof that Potchitra bridges faiths, echoing shared humanity. But Dukhushyam painted new verses on old cloth. In his scrolls, gods walked beside revolutionaries. His brushes traced the agony of HIV, the outcry against deforestation, the demand for clean drinking water. Even Congress politicians weren’t spared — his satirical “Congress Biplobi” scrolls stirred both laughter and thought.

Born in 1946 in a humble Kolkata hospital, Dukhushyam turned poverty into palette. From brick dust and turmeric, from leaf sap and soot — he conjured colors. Glue from babla trees bound his truth to fabric. In 1970, he founded a school to teach rural women this sacred art. His works crossed oceans — now displayed in museums from London’s V&A to galleries in France, Italy, Australia, and Bangladesh.

Yet like many ancient crafts, Potchitra now faces time’s erosion. Unlike electric lights that breathed life into theater and music, scroll art battles obsolescence. The patience required to paint and the time needed to listen — both are rare luxuries in today’s world. Original works are expensive, leading buyers to settle for mass-produced mediocrity. Many true artists go underpaid, unpraised.

As Bangladeshi Patua Shambhu Acharya once said — workshops in schools and art institutes are vital. For only when the people understand not just the price but the painstaking soul behind Potchitra, can it truly survive.

Today, commercial winds have altered the landscape. Artificial paints replace natural ones. Compact canvas replaces the majestic scroll. Kalighat-style miniatures gain demand, while divine narratives retreat. As Bhaskar Chitrakar of Kalighat noted, caricatures sell — but sacredness fades.

Yet, in every line drawn by a Patua, in every note of Poter Gaan, Bengal still breathes — a land that sings through scrolls, remembers through colors, and resists forgetting through art.

About the Creator

Riham Rahman

Writer, History analyzer, South Asian geo-politics analyst, Bengali culture researcher

Aspiring writer and student with a deep curiosity for history, science, and South Asian geopolitics and Bengali culture.

Asp

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.