Hagiographic Icon

Origin and Evolution of Russian Iconography

The phenomenon of a hagiographic icon always raises a lot of questions for those who are just beginning to get acquainted with Byzantine and ancient Russian art. We suggest you to understand its history and the contribution that Russian iconography has brought to it.

Already in the first centuries of Christianity's existence, theological disputes concerned not only the dogmatic foundations of the young religion, but also the issue of icon worship. At that time, the holy fathers considered one of the most important functions of the icon to be the enlightenment of the believers, which were not always able to independently read the gospel and hagiographic texts. Apparently, the first hagiographic icons appear quite early, including, in addition to the image of the saint himself, also scenes of his righteous life, miracles or martyrdom. Both Byzantine and Russian iconography went hand in hand with hagiographic icons, with such an abundance of diverse subjects from hagiography.

It is not known exactly when the first hagiographic icons appeared – the oldest extant ones date back to the XII century. So, at the moment, the earliest hagiographic image is considered to be the Byzantine icon of St. Marina, presumably dating from the end of the XII century (Byzantine Museum, Nicosia). And although this is the earliest monument, in this example we see an already established and traditional composition: in the center there is a large waist icon of the saint, and there are scenes from her life in the margins, in stamps. Traditionally, reading the plots on such icons begins from the upper-left corner and continues line by line, from left to right, by analogy with reading a book.

This connection of iconography with hagiography is by no means accidental: in their work, icon painters have always relied on hagiographic texts known to them. Thus, the most important source for Byzantine iconographers has always been the minology, compiled in the 10th century by Simeon Metaphrastus, secretary of the Byzantine emperors Leo VI the Philosopher and Constantine VII. While working on the minology, Simeon Metaphrastus did a titanic job: he outlined all the lives of saints known at that time and grouped them by months and days of church veneration. Of course, such a valuable and convenient source of knowledge became an important source for Byzantine icon painters, and, therefore, Russian iconography was indirectly influenced by it.

In Ancient Rus, the situation developed differently. Translated from Greek into Slavic, hagiographic collections, Monthly or Synaxari, have been widely distributed since the beginning of the XII century under the name Prologues. However, in addition to the Prologues that told about the general Christian and Byzantine saints, there were other sources for artists in ancient Russian literature: lives in other editions, often more extensive and detailed than the printed ones, and, finally, the lives of saints canonized directly in Russia, especially Saints Boris and Gleb. Their lives existed in different editions, but the author of the most common one was the famous Monk Nestor the Chronicler. In the future, these texts will be in demand in the Moscow Principality as well: the Russian iconography of saints will be largely based on them.

The oldest extant hagiographic icon dates back to the second half of the XIII century – this is the icon "The Prophet Elijah in the desert, with life and Deesis" from the village of Vybuty. This icon, like many later images of the 14th century, is still quite closely associated with the Byzantine iconographic tradition. Russian iconography at this time was developing primarily in new scenes of miracles that had already happened in Russia. This is especially evident in the example of the life cycles of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, one of the most revered saints. For example, one of favorites was the Kiev miracle from the icon of St. Nicholas the Wet (XI century, disappeared during World War II) about the rescue of a baby drowned in the Dnieper River, found soaked but unharmed under the icon of the saint. One of the oldest examples of the inclusion of this miracle in the composition of the hagiographic cycle is the icon of the late XIV – early XV century from the church of St. Nicholas in Kievets, a settlement of Kievans near Moscow.

The most widespread distribution of hagiographic icons occurred in the last third of the XV – beginning of the XVI centuries. During this period, Russian iconography developed rapidly and was saturated with new subjects developed by the Moscow iconographer Dionysius and his sons. They worked at a time when the lives of Moscow saints, for example, St. Sergius of Radonezh, Saints Peter and Alexy of Moscow, were already widely known, and poetic and sometimes personal hagiographic texts created in the first half of the XV century by Epiphanius the Wise, were processed by an excellent writer who arrived from Mount Athos, Pachomius Lagofet (Serbian).

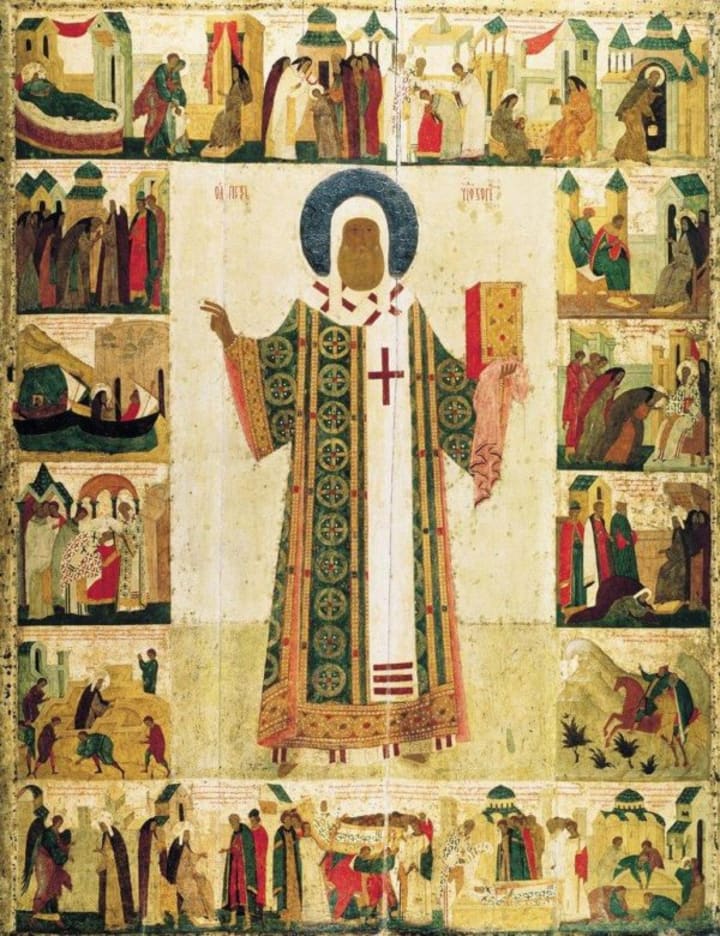

Perhaps the most striking examples of the development of the hagiographic icon during this period are the icons of Saints Peter and Alexy of Moscow, presumably created around 1480 for the newly built and consecrated Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. Elongated, as if floating figures, delicate coloring – all these have become distinctive features of Dionysius' style. Russian iconography and the new types of compositions that have developed on Russian land, however, are more interesting in this case. Thus, despite the widespread veneration of St. Peter, only isolated images of him could be found before that.

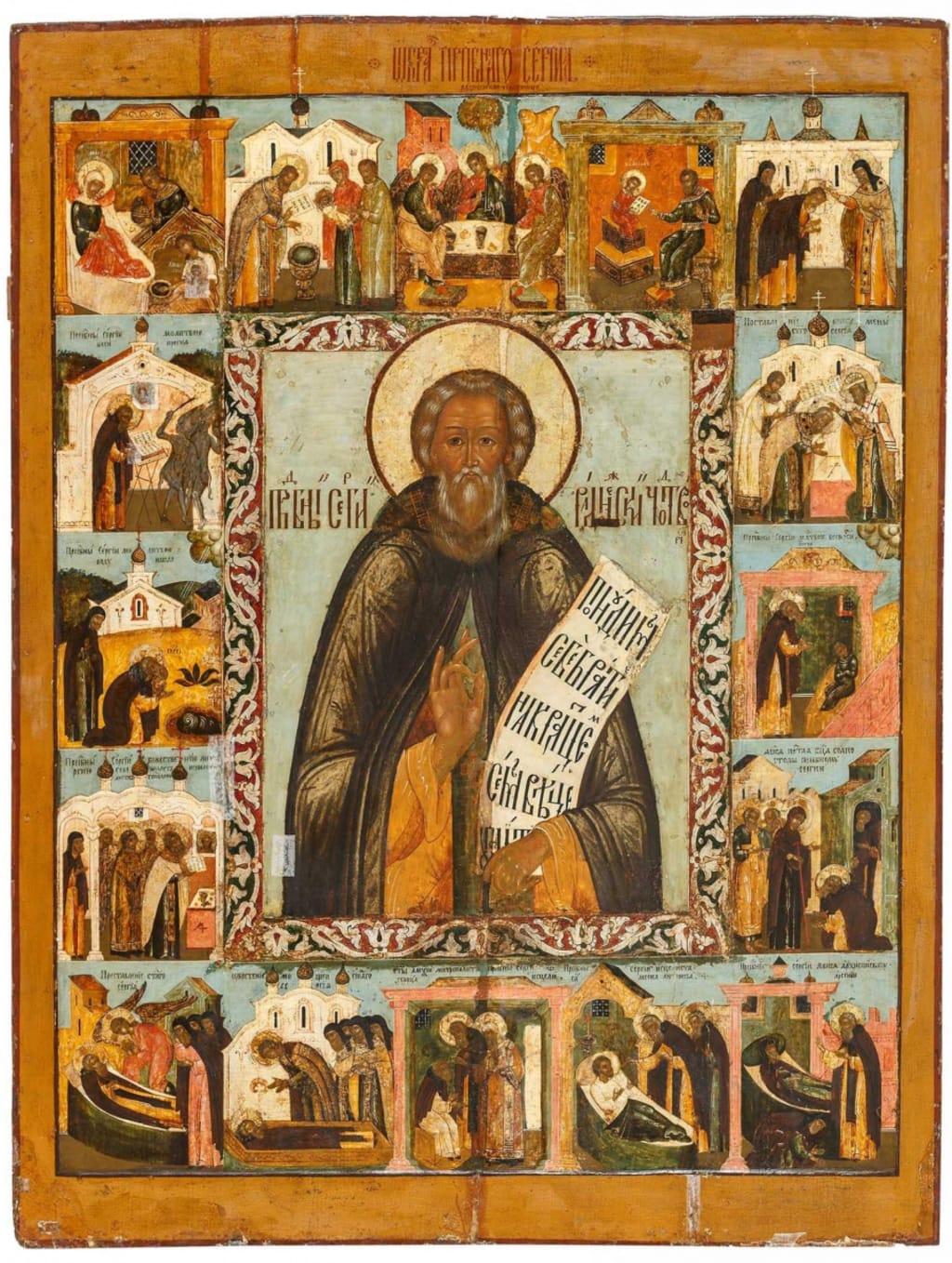

Moreover, in the workshop of Dionysius, a new principle of the arrangement of hagiographic stamps was developed: in the upper and lower rows, the scenes were no longer divided into separate delimited compositions, but, on the contrary, combined into an integral elegant frieze, most often with the help of architecture and figures of minor characters facing the main characters. Such complex, multi-figure compositions developed by Dionysius, along with the stylistic features of his painting, will continue to develop in monuments associated with the workshop of his son Theodosius, which, for example, is seen in the icon "St. Sergius of Radonezh, with the life" of the first third of the XVI century. It was in these workshops that Russian iconography was enriched not only with fresh variations of traditional compositions, but also with fundamentally new ones – for example, in the paintings of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Virgin of the Ferapontov Monastery in 1502, Dionysius and his sons actively reproduce the hymns of the Virgin in colors: akathist, "Victorious to the Risen Voivode...", "Rejoices about You..."

The innovations of the workshops of Dionysius and Theodosius largely transformed the entire experience of Byzantine and Ancient Russian artists accumulated over the centuries, and their art largely laid the foundations of the art of the mature XVI century – the time when Russian iconography, responding to the challenges of its era, will enter a fundamentally new stage of development.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.