When the Artist Becomes the Art

The Picture of Dorian Gray as a Mirror of Wilde’s Forbidden Self

We like to think we can separate the art from the artist, but can we, really?

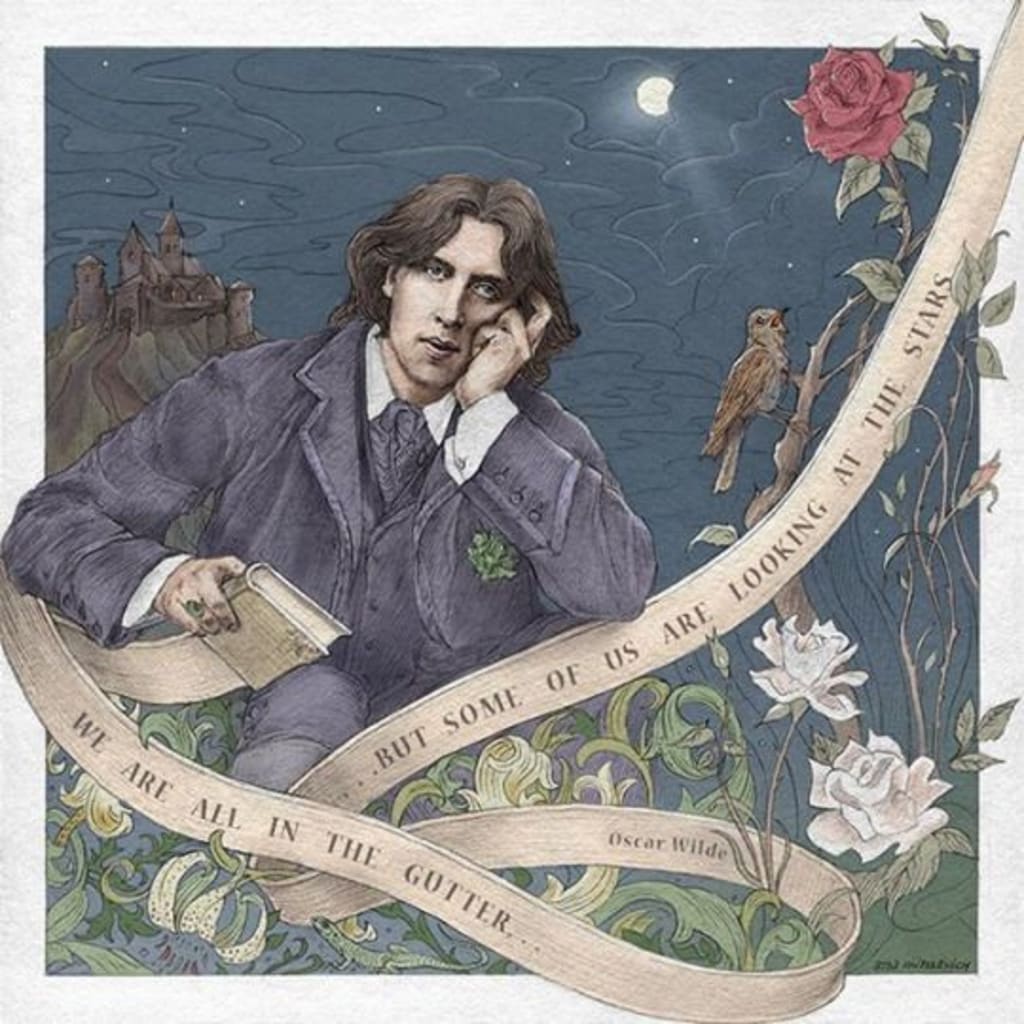

Art is born from the same place as sin. It mainly emerges from conflict: between what is felt and what is permitted, between the self that is lived and the self that must be hidden. No figure embodies this tension more vividly than Oscar Wilde: a man who transformed his own contradictions into style, wit, and devastating clarity. His novel The Picture of Dorian Gray is not merely a tale of aesthetic decadence but the battleground on which this question is fought.

On one side of the canvas, the argument for separation appears in the bold, defiant strokes of Wilde’s own aestheticism. He championed l’art pour l’art, insisting that “the sphere of Art and the sphere of Ethics are absolutely distinct and separate.” In his provocative preface to Dorian Gray, he declares, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” This philosophy imagines the artwork as an autonomous object; to insist that art is forever chained to the biography of its maker is to diminish its capacity to speak to anyone, anywhere. If we could only read books whose authors lived spotless lives, literature itself would collapse under the weight of human imperfection. Seen this way, The Picture of Dorian Gray becomes something timeless and independent: a meditation on youth, vanity, influence, and decay that speaks as powerfully to modern readers as it did to Victorian ones. The novel does not require knowledge of Wilde’s scandals, desires, or trials to seduce us. Its beauty stands on its own, shimmering, dangerous, and complete.

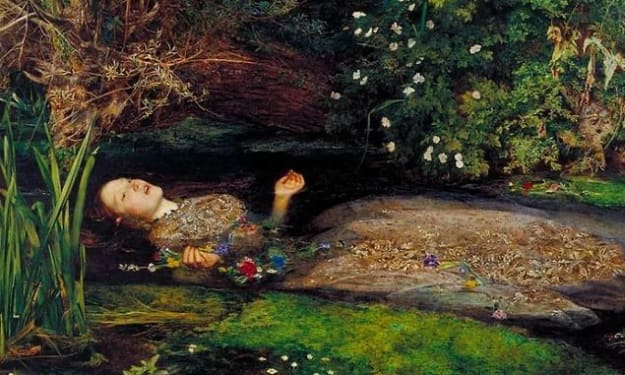

Yet, to assert this separation is to ignore the portrait’s own sinister whisper. To engage with this book is to hold the crack in the soul of the man who wrote it. At its core, the narrative dramatizes the consequences of divorcing beauty from ethics, a central tenet of l’art pour l’art, and ultimately reveals the impossibility of such separation when the artwork becomes an extension of the self. The novel functions as a prophetic, metaphorical autobiography, with Basil Hallward, Lord Henry, and Dorian himself representing fragmented facets of Wilde’s psyche and public persona. Basil embodies Wilde’s vulnerable sincerity, Lord Henry his seductive wit and intellectual cruelty, and Dorian the beautiful surface upon which society projects both desire and disgust. When Dorian destroys the portrait and perishes, it is impossible not to see a shadow of Wilde’s own tragic fall: a man destroyed by the very society that was mesmerized by his surface. We read not just the words on the page, but the silence between them: the unspoken fears, desires, and pains of the author. The artwork is a piece of the artist’s soul rendered in ink or paint; to try and sever that link is to deny the profound, messy humanity from which all creation springs. This connection grows impossible to ignore when we consider Wilde’s life beyond the page. As a man who loved other men in a society that criminalized such love, Wilde lived under constant threat of exposure. When his relationships were revealed, the same society that had adored his brilliance turned vicious. Wilde was not merely condemned but also erased, imprisoned, disgraced, stripped of his voice, and ultimately destroyed. Like Dorian, Wilde was punished not for corruption of the soul, but for the refusal to keep it hidden enough.

Nowhere is the impossibility of separation clearer than in the novel’s publication history. Early versions of The Picture of Dorian Gray contained language that hinted too openly at homoerotic desire, particularly Basil’s devotion to Dorian. Editors intervened. Passages were cut, softened, and moralized to appease Victorian sensibilities. The text was altered because of who Wilde was believed to be. His life shaped not only how the novel was read, but what it was allowed to say. The result is a work haunted by absence. What remains is eloquent, but what is missing speaks just as loudly. To read Dorian Gray with this knowledge does not ruin the novel. On the contrary, it sharpens it. We begin to read not only the words on the page, but the silences between them: the unspoken fears, desires, and pains Wilde could not safely articulate. In this way, the novel itself becomes a censored body, mirroring the fate of its author and echoing the very theme it condemns: the violent attempt to hide what society refuses to accept.

In the end, the question is not whether we can separate art from the artist, but whether we are brave enough to look at them together. Because art is never pure. Creation is born from the messy edges of life, shaped by desire and fear, by what is allowed and what is forbidden. The artist’s fingerprints remain on every page, even when the words are edited, even when the truth is hidden. And so the book becomes a portrait that refuses to be detached from its creator. We cannot fully separate art from the artist, because the art is a piece of a life, and that life continues to echo in the silence between the lines.

About the Creator

Yasmine Lagras

creative writer , poet and researcher.

Aspiring to reach more people.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.