Gulf Coast Native: Another Adventure in Rare Fiber

The search for a heritage breed sheep continues

Introduction

My future is foggy.

While I know I want a farm, I don’t necessarily know where. It could be in the Northern Wilds, or on a tropical island somewhere amidst the ocean. In the event of the latter, I would need a sheep that can handle heat and humidity. And as most of you likely know, I’m a believer in conservation and environmentalism, so I want a heritage breed that needs my help.

Enter the Gulf Coast Native, one of the most heat tolerant sheep on the planet.

But what is their wool like? Well, I bought a little fiber, a mere two ounces grown by a little lamb named Bernie who was cared for by The Ornery Shepherd (buy her amazing stuff here), and gave it a spin.

In this article, I continue my search for a heritage breed, the fiber of which I love to work with and wear, in the hopes that this also brings more awareness to heritage breeds that are endangered and need our help by raising and using their glorious fiber. Here is my adventure into the Gulf Coast Native sheep.

The Gulf Coast Native Sheep

The Gulf Coast Native Sheep is a fascinating creature. They were brought to North America in the 1500s from Spain. Here they were bred for parasite resistance, heat tolerance, and a low likelihood of developing foot rot in the wet climates of the Deep South. They are a medium sized sheep, some having horns and some being polled, and they lamb easily and can produce multiple lambs on good forage.

They are currently listed as “Critical” by the Livestock Conservancy. To learn more about the Gulf Coast Native Sheep, visit the Livestock Conservancy’s Conservation Priority List.

Spinning

I have spun a few different fibers in my short time as a spinner, and so far none of them have made me spin the way I spun this Gulf Coast Native fiber.

For one, the fiber has a very short staple length. In this case, each individual hair was never more than two inches long. Now this was also a lamb’s fleece, so it probably has a shorter staple than an adult. But even so, being a down breed, the average fiber is likely not much longer than the roving I had.

The result from this two-inch fluff? A very short short forward draft. If you’ve seen me spin, you know I’m a short forward kinda gal. I like the smoothness and the control it gives me. I’ve tried long draw and the results are… not good. Veeeeery slubby. And in the case of this short staple length, long draw might have been a better way of going about spinning this fiber. But I only had two ounces of this precious rare breed and couldn’t bring myself to relinquish control. So the result was that I had to keep my hands close together—quite close together. So close it looked almost like when I spin cotton off the seed.

Another interesting characteristic that influenced my spinning method was that it was fluffy. When you hear “down” you probably think of something fluffy, and the down nature of the Gulf Coast Native matches that connotation quite well. It has an uneven crimp and resilience, lending to a springy behavior. Because of this texture and the short staple, the roving I have desired to be spun very fine. This worked well because the diameter of the fibers themselves was quite fine—I would say, without any real way of measuring the micron count, near merino fineness. What I ended up spinning as a single was likely fingering weight, if not close to lace.

Now this all sounds like it worked out quite nicely, but this spin wasn’t without literal bumps along the way. This particular roving had lots of what I thought to be seconds. Teeny, tiny, little lumps of fiber scattered generously throughout the roving. I couldn’t tell if they were due to the nature of the lamb’s fleece, or if they hadn’t been skirted from the freshly shorn blanket, or if they were leftovers on the carder during processing. I thought they would be the bane of my spin, as every time they came between my fingers and the wheel orifice, they made great lumps in my nice, even thread. How was I going to chain ply with all these lumps stopping up the pull of the yarn through the loop?

Oh, but they were a gift.

I eventually let go of the desire for a perfectly even yarn. I would try my best for even between the lumps, but I accepted that I couldn’t pick every little eighth-inch fluff out of the roving. And as the yarn wound onto the bobbin, I noticed a beautiful texture was being created, giving the impression of coziness and warmth, looking inviting and affectionate. It was a texture many yarn manufacturers take great pains to make artificially, and here it was on my bobbin, as natural as can be.

And when I made to chain ply, those little lumps gave me absolutely no trouble. I did notice having to wiggle my fingers a little to pass the thread through the loop, but it never hampered my progress.

The fiber chain plied quite nicely, too. There were instances where it looked like the fibers lined up side by side and then twisted like a ribbon, but eventually enough twist went into the fiber that such a structure melded in with the rest. This Gulf Coast Native is a very clingy fiber—though it is soft and drafts easily, it does like to stick to itself, which makes spinning it quite easy, from drafting to plying.

I got 128 yards out of two ounces. The overall result from spinning was a soft, fluffy, textured yet even yarn that looks inviting for knitting. The knitting is yet to be tested, but there’s one more step to take, one I didn’t take in my Teeswater article, a special adventure that I’ve never done before; natural dyeing with foraged goldenrod.

Dyeing

Goldenrod is an invasive species in the U.S. It grows mainly in prairies, sending up tall, narrow stalks in early fall and blooming in several near-vertical spikes of flowers at the very top. These flowers are a warm, sunshiny yellow, hence the “golden” in goldenrod. They are one of the last foods for pollinators and usher in the fall season in style.

It’s no wonder, then, that natural dyers way back when saw this lovely little plant, festooning the hillsides with vibrant color, and thought, “Yeah, I bet that would be pretty on my yarn.”

And indeed it is. Goldenrod yields two lovely hues: the obvious bright gold (with an alum mordant), and a sage-like green (with an iron mordant). As much as I like green, and sage-y green especially, I wanted to preserve that delicious yellow that goldenrod is so famous for.

…Plus I like alum as a mordant and didn’t have the time to make an iron mordant…. Maybe next time….

So I began. I used a recipe from Maria Roderick. It is a well-explained recipe; concise while still being thorough. Plus it used a method that let me skip a step—she adds the alum right to the strained flower water! No mordant dip, no second pot, just one simmer session for the flowers and one for the yarn.

But first thing’s first; gather flowers. Armed with a tote bag and a hand pruner my mother has had for decades, I headed out into the wild to forage my heart out… within reason. Thanks to the lovely weather, I was able to wear clothing head to toe, including a pair of tall boots, as I was about to forge my way through the tall grasses, scrub, and flowers to gather the goldenrod. And here’s the thing about goldenrod; you look at it from a distance, and it looks like a plant of middling, modest size. But you get up to them and you find some of them are about as tall as you are.

And the bugs love ‘em. Beetles, ants, flies, bumblebees, and best of all, wasps. I am not a bug person. The first time I saw a wasp on the flowers, I was livid. I reminded myself that of course wasps would like goldenrod, they’re pollinators, thank you wasps for pollinating (she said through clenched teeth). But I didn’t want it in my bag or near my bare hand, so I shook the plant stalk gently thinking surely it will fly away if disturbed… to no effect. So I poked at it with the pruners. Still the wasp fiddled away at the many tiny flowers. It was at that point I realized that if that wouldn’t get it to fly away, me brushing by the plants wouldn’t disturb them either. Perhaps the cool temperatures had made them docile, or maybe it was the satisfaction of eating away at sweet goldenrod nectar that had them content. So I decided this was nature’s way of telling me not to take that particular flower array and moved on through the prairie, leaving plants that had wasps on them.

This was a little disheartening, however, as I had watched the goldenrod bloom and fade over the past week. I was worried I wouldn’t have enough to make sufficient pigment for my skein. When I got to the first patch of goldenrod, I was terribly sad, for it looked like all the blooms were spent. I trudged in anyway, hoping I could find a spare one here and there. As I did, I realized there were more goldenrod at the height of their bloom than one would know from viewing at a distance. I ended up only needing to visit two patches to harvest a significant amount of flower arrays, and I left many behind, adhering to the rule of taking no more than a third. Had I foraged at the height of the bloom, I would have had more goldenrod than I’d known what to do with, and still have left a smorgaspord for the pollinators.

So I returned home, overjoyed with my little venture into foraging, and deposited the flowers into my little thrifted dye pot… which turned out to be aluminum. Yup, you natural dyers all just gave a collected sigh of disappointment. For those who don’t know, you want to dye in stainless steel or enamel. Aluminum will change the color of your dye. In this case, the yellow will have a green cast to it. I didn’t have access to another pot, so I just rolled with it. The color would still be yellow, just not the brightest yellow there ever was.

I filled my pot with a gallon of water and set it to boil. The aroma the flowers produced was heavenly, like a strong tea or some other delicious botanical concoction. It surprised me—I had not expected such a strong scent, and it filled the kitchen. I could even smell it at times while sitting on my couch.

Eventually it was time to strain. Here’s something I loved about my pot; it’s a blanching pot. With very small holes. I didn’t have a dedicated dye strainer, or any cheesecloth, but I could boil the flowers in the drainer insert, then just lift the flowers out of the water, leaving the goldenrod extract in the body of the pot. Easy as pie, and very effective. There was very little vegetable matter left in the water. Some, but very little.

Then it was time to add the mordant; a tablespoon of alum. It roiled within the water as I shook it in, and immediately turned the water opaque and bright yellow. It was one of the most satisfying things I’ve ever done on a stove. I wish I’d known that was what would happen; I would have filmed it, it was so shocking an effect.

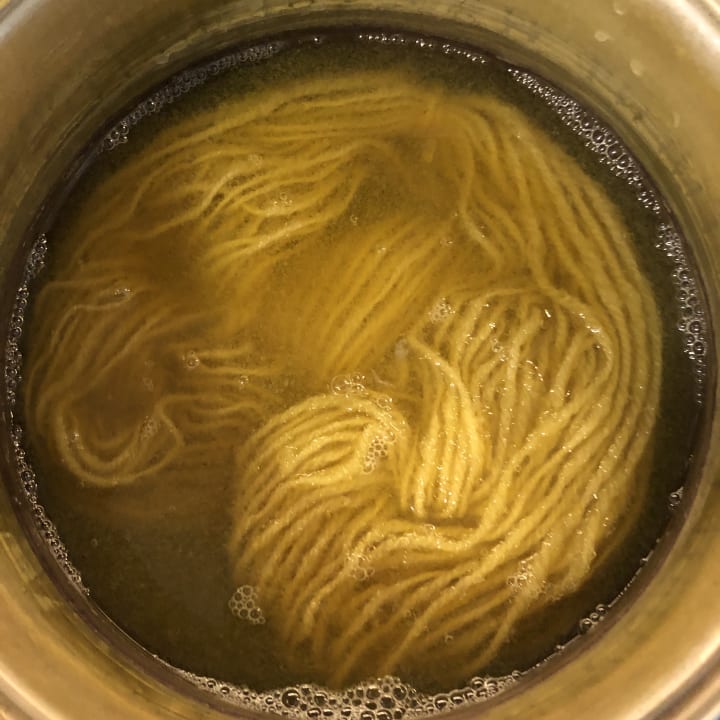

I stirred the mixture for fifteen minutes, then the big moment came. I wetted my handspun and dunked it into the dye bath. It took the color immediately. It is very tempting to pull yarn out and goggle at it when the dye is so effective, but I knew to just drop it all in and let it simmer for an hour, adjusting the stove setting now and again to make sure it wouldn’t boil.

Once the time was up and the water had cooled, I pulled it out for the final reveal. The Gulf Coast Native wool had taken on the color beautifully, showing a vibrant yellow with just a touch of green, which ultimately just made it look more natural and earthy. Some wools don’t take dye very well, and my experience is limited, but I would say this wool did a very nice job of capturing the essence of goldenrod.

Knitting

Knitting with a new breed of handspun wool always requires a lot of experimentation. The actions of the yarn are unfamiliar, and the consistency of the spin is uneven because a good portion of the first quarter or so was spun differently than the other three quarters when the rhythm is found. Because of this, finding the right pattern takes a lot of yes, then no, then pull it out, then yes, then no, then pull it out, and on and on as such. Not to mention the size of the item one might get out of the amount of yarn one has to use. Even the size of the needle or hook is a mystery to be solved. But all this is not fruitless; it gives one lots of experience with this new fiber.

One thing that stood out to me is that Gulf Coast Native is very lightweight. As you recall, I only got two ounces of fiber, but I got a whole 128 yards from those ounces, and some of it was not spun very fine at all, and it was chain plied! Typically from two ounces I can make a headband and that’s about it. I went through several patterns, but ultimately ended up making an entire lace cowl. This is astonishing. Sometimes I can’t even get a decent-sized cowl out of four ounces. This means the garment is incredibly comfortable and full of trapped air that can keep a person very warm.

Another thing I learned about this fiber is that it is very clingy. Something about the texture makes it like to stick to itself. And yet it was not awkward or uncomfortable to work with. The only thing it really hindered was knitting continental, with the fiber tracking through my left hand. Tensioning in continental (at least in the way I knit continental; I knit this way just fine but am not as experienced as some) relies heavily on the weight of the yarn and the slippage of the fiber around and between the fingers. This does not work well for Gulf Coast Native because of the way it sticks to itself, causing excessive tension and too tight stitches. So I knit English style on most of my projects as I worked and reworked them, since I throw in such a way that I can pull the yarn off the ball while knitting without changing the tension on the stitch.

There is also the matter of definition. Gulf Coast Native has excellent definition. While it is fun to have some yarns that get a great halo effect, it can muddy up any pattern knit into the garment and all that work of cables or lace is lost amongst the fluff. While Gulf Coast has texture, it does not have much halo and patterns are clearly visible. It is very rewarding to come up with a pattern, give it a whirl, and see it clearly and elegantly revealed in the finished item.

The texture of this fiber is worth mentioning, too. Although it does not feel necessarily “silky soft” to the touch, it is not scratchy. Some sensitive skin may notice a discomfort to it, but it is not so uncomfortable as to be unwearable. I have fairly sensitive skin myself and am very aware of softness and scratchiness in all fabrics, and I find Gulf Coast Native to be very comfortable. Not to mention it is very squishy, which makes it seem even softer than it is.

Overall, Gulf Coast Native is a joyful yarn to knit or crochet with, with a very pleasant end result. It is fairly easy to work with, is nice and soft and comfortable to wear, and looks damn good.

The Finished Item: After Blocking

The item I made was a lace pattern, and anyone who’s knit lace knows that until it’s been blocked, it looks like shit (pardon the phraseology, it was necessary to describe unblocked lace). But I lost my blocking boards in the move, so have no good way to properly block an item. But necessity is the mother of invention, so I laid down a clean beach towel in the bottom of my shower, wet my Gulf Coast cowl, and laid it neatly on the towel, as flat and straight as I could get it to stay. No pins, no blocking wires, nothing special, just a “lay flat to dry” situation, with my fan set up as close as I could get it what with the cord length and the distance to the outlet.

Well… it went just swimmingly. It took some time to dry (we have bad air circulation in my apartment, and the fan wasn’t a huge help) but once it was all done, it was a wonderful, flowing, draping but still springy, work of art! I tell yah’, this Gulf Coast Native wool is just about perfect. The fabric was delicate but substantial, the pattern clear and tidy, and so lightweight but still warm. It was utterly pleasing to handle this completed piece.

“Let me explain…. No, there is too much; let me sum up.”

From a delicate spin, to an adventurous dye process, to a cozy knit, to a beautiful end result, Gulf Coast Native has been an unexpected joy to work with. It challenges, but does not push. It accepts color without protest. It becomes something delicate, yet robust. It is textured, yet soft. Should I land somewhere warm — an island, the Deep South, the middle of nowhere — I would most definitely have a flock of Gulf Coast Native sheep. Thank you to the Ornery Shepherd for sharing this lovely fiber! And thank you Bernie for growing it!

For more information about the Gulf Coast Native Sheep, visit the Livestock Conservancy’s page on the breed: https://livestockconservancy.org/heritage-breeds/heritage-breeds-list/gulf-coast-sheep/

Enjoyed learning about this rare wool? Share this article on social media: doing so will spread awareness about the Gulf Coast Native sheep and help save the breed. Thank ewe!

Enjoyed reading this article? Support the writer (that’s me!) by sharing this article, giving it a like, or leaving a tip. Every little bit helps both my writing career and my fiber arts business.

Want to purchase the item I made in this article? Find it in my web shop: https://theolivetreefiberarts.weebly.com/store/p16/Gulf_Coast_Native_Knit_Lace_Cowl_-_Hand_Spun%2C_Naturally_Dyed%2C_Hand_Knit.html#/ (while supplies last.)

Want to read other articles I’ve written? Visit my Vocal Writer’s Page here: https://shopping-feedback.today/authors/olivia-beech%3C/a%3E or stay up to date with new articles posted on my Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Olivia-Beech-104064404989121

Interested in supporting my Fiber arts business? Check out my website: https://theolivetreefiberarts.weebly.com/#/ or follow me on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/theolivetreefiberarts/ to stay up-to-date on new projects and products.

Thank you for reading and engaging!

About the Creator

Ophelia Keane Braeden

Quirky fiction, hand-crafty non-fiction, random poetry. The muse strikes from all angles! Grab your favorite floatation device and join me on the wandering river of writerly flow!

~

None of my writing is ever touched by AI.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.